In the world of Australian equities, few names carry the gravitas of Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). It’s the blue-chip darling of retirees, fund managers, and index-huggers alike. However, most fund managers are underweight the $300 billion banking behemoth, especially those that followed calls early last year by the sell-side analysts to sell the banks. As the share price continues its gravity-defying ascent, recently notching a record high of over $191, investors are left wondering: is this a triumph of fundamentals, or are we witnessing the makings of another valuation bubble?

In this week’s piece, Atlas tries to unpack the forces at play, the implications for the broader market, and what this means for investors navigating a market increasingly shaped by passive flows and sentiment over substance.

Why do Fund Managers Hate This Rally

The hatred of this rally in CBA’s share price among fund managers is due to selling down their positions in the bank over the past 18 months, which has then caused underperformance against the benchmark ASX200 index. When a smaller company experiences spectacular share price growth, it will have a minimal impact on the ASX 200; however, CBA has delivered a total return of 55% over the past 12 months, far ahead of the benchmark return of 13%. With an average index weight of 10% over the last 12 months, if fund managers had not owned CBA at all, they would have to find over 3.5% of fund performance elsewhere to match the index performance. Not an easy task.

As a disclaimer, Atlas’ stance is now one of strong dislike not hatred towards the CBA rally, after being slow to reduce our holdings. The Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio has sold three times over the past six months to move to an underweight in CBA: in December ($156), April ($167), and June ($181). Each time prematurely patting ourselves on the back thinking that we had picked the share price peak.

Price Earnings Expansion Rally

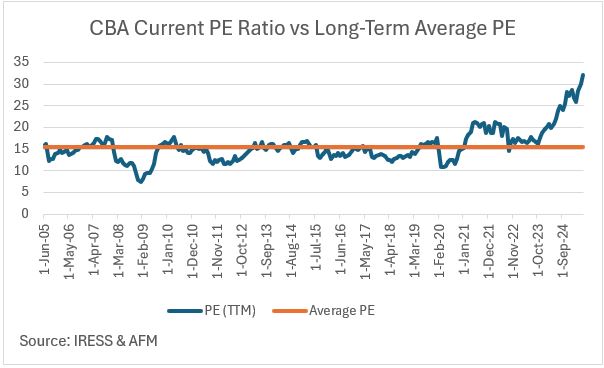

The recent rally in the share price of CBA has not been accompanied by higher earnings, but rather the same earnings becoming more expensive for investors to purchase. As you can see from the table below, CBA’s price-to-earnings multiple expanded in 2024 and 2025 from its long-term average of 15 times, tracking the move in the share price from $100 to $191.

The bulk of CBA’s profits come from loans made to households and corporates, which, unlike luxury consumer goods like Louis Vuitton handbags or Glenfarclas 25-year-old single malt whisky, have no brand premium attached. Despite extensive advertising, borrowers remain indifferent about which bank to choose for their mortgage funding. Indeed, CBA operates in a domestic banking market with limited credit growth in Australia, selling an identical product to that offered by four other competitors (now including Macquarie), all of which have the same cost of production (capital). By way of comparison, CBA’s competitors (Westpac, ANZ and NAB) trade on a average PE ratio of 15.5 times with a 4.8% yield.

This current rally has seen CBA move into the world’s top ten most valuable banks and become the first developed market bank in history to trade at a multiple greater than 30 times earnings.

Passive Flows Driving the Market

One of the key drivers behind CBA’s meteoric rise has little to do with its earnings or strategy. Instead, it’s the sheer weight of money flowing into passive investment vehicles. As the largest constituent of the ASX 200, CBA receives the lion’s share of every dollar that flows into index-tracking funds, such as Vanguard’s VAS or Betashares’ A200. This creates a self-reinforcing loop: rising prices attract more inflows, which in turn push prices higher. It’s a virtuous cycle—until it isn’t. Currently, CBA comprises 12% of the ASX 200, the highest weighting of a single company in the ASX 200 since News Corp reached 15% during the Tech boom of 2000. BHP also hit 15% in February 2009, although this was more a result of a stable share price in the face of other large companies experiencing meltdowns during the depths of the GFC. Not dissimlar to Steve Bradbury’s performance on the ice in Salt Lake City in 2002!

While CBA current dominance of the ASX 200 is quite significant, there have been more extreme cases in other developed stock markets. I started my career in Canada working for a large Vancouver-based fund manager and unfortunately, that coincided with the “dot.com” boom. During July 2000, telco stock Nortel peaked at 35% of the TSE 300 Composite, with the tech behemoth moving the benchmark index by itself. Now that was a truly hated rally, with many fund managers including the one that I worked for having a 10% position limit on any one stock in the portfolio!

The shorts have already been burned

Shorting the Australian banks has historically ended up as a widow-maker trade. A “Widow-Maker” trade in the hedge fund world is a short-selling of an overvalued asset that may make sense intellectually. Still, the share price continues to rise despite the bearish investment thesis. As it continues to rise, the short seller is forced to post ever-increasing amounts of cash into their margin account, increasing the chance that the fund manager has a heart attack or gets fired.

US and European fund managers have been systematically shorting Australian banks based on the seductive story that they are overvalued compared to their domestic peers. International investors have historically made mistakes by assuming that Australian banks operate in the same regulatory environment as their domestic banks. The basis for their thesis is that four banks from a small backwater in the financial world have little business, being amongst the largest in the world.

Short interest in CBA has been relatively low in recent years, peaking in December 2023 at 1.8%, and currently stands at 0.88%. CBA’s rising share price would have seen continual margin calls being issued to short sellers, until the short seller gives up and closes out the position by buying back the CBA shares on the market.

Whilst this 0.9% decrease in the outstanding stock being sold short may seem insignificant, if the average purchase price for hedge funds covering their short positions were $140, it would equate to over $2.1 billion in hedge fund managers buying CBA stock with gritted teeth.

This has all been achieved without CBA turning on the buyback machine

The last time CBA bought back any shares from its $1 billion on-market buyback was on November 2024 at $152 per share, leaving $700 million of buyback outstanding. CBA management is incentivised to return excess capital to shareholders as bank management teams are awarded bonuses based on their return on equity (ROE). The ROE increases as the bank buys back shares, reducing the equity divisor on its return. In CBA’s February result, the bank announced that it had a capital ratio of 12.2% well above the minimum capital ratio set by APRA of 11%. CBA’s management deciding not to repurchase their own shares, despite having financial incentives to do so, indicates what company “insiders” think of the bank’s share price.

Why would global managers be buying CBA?

The terrible historical offshore expansions conducted by the other major Australian banks, which saw billions of shareholders’ value eroded, have led CBA to sensibly restrict its operations to the Australian domestic banking market. Whilst this is a limited market opportunity, it does create a lot more certainty and consistent and predictable earnings that are only exposed to a small subsector of the global economy. So, in a world of rising geopolitical risk and economic uncertainty, investors often gravitate toward quality and stability. CBA’s conservative balance sheet, strong capital buffers, and predictable dividend stream make it a safe haven for global investors. Indeed, earlier in June, a Texas-based investment manager, Fisher Investments, revealed that they had spent $1 billion buying CBA shares over the previous two weeks, at a level we estimate to be around $170 per share.

Our take:

While Commonwealth Bank has long been the “Steven Bradbury” of Australian banking—winning by avoiding the missteps of its peers—its current valuation appears to be running well ahead of fundamentals. At over 30x forward earnings and a dividend yield below the broader market, investors are now paying growth-stock multiples for what is, in essence, a mature, low-growth stock with a highly leveraged balance sheet and limited to no international expansion prospects.

Historically, banks like CBA have traded at a premium due to their robust balance sheets and consistent dividend payments. But today’s premium feels more like a product of passive fund flows, index weightings, and a scarcity of large-cap alternatives than a reflection of earnings growth. Real dividends, when adjusted for inflation, remain below 2015 levels, yet the share price has nearly doubled since then.

As we’ve seen in past decades—from Japanese megabanks in the ’90s to US giants pre-GFC—being the world’s most valuable bank is often a prelude to underperformance. While CBA remains a high-quality franchise, the current price implies perfection. And in markets, perfection rarely lasts, and there will be many fund managers in June 2025 praying for the bank’s share price to correct to more rational levels.