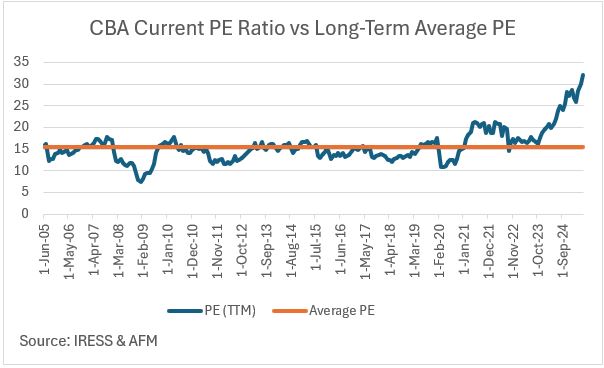

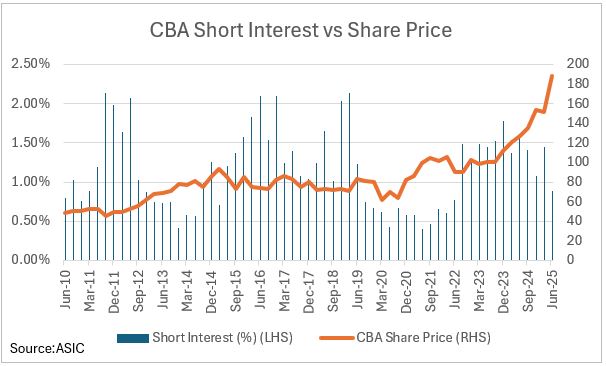

| This article was originally posted on Livewire: Link Here The past year has been quite volatile for investors. August saw a sharp sell-off in global shares after a surprise hike in Japanese interest rates led to an unwind in the Japanese yen “carry trade”. This trade saw hedge funds that had borrowed in cheap yen having to sell high-yielding global shares to repay their loans. Following this, the markets recovered losses and ground higher on the back of the now laughable theory that the Trump presidency would be more business-friendly than the previous administration. From mid-February to April, the ASX collapsed by 14% on the back of very business-unfriendly trade policies from the USA, which seemed to vary by the week. However, the Australian share market was less impacted by vacillating US tariffs than other global markets due to the domestic focus of many of our companies. Indeed, in the last quarter of FY 2025, the ASX 200 was one of the better-performing markets, due to its perceived safe haven, led by the powerhouse CBA (+48%), which saw the most hated rally on the ASX. Despite what feels like a bruising twelve months for investors, the ASX 200 has enjoyed a relatively strong year, up +10% or +13.8% (including dividends). Surprisingly, a very similar return to what investors enjoyed in the 2023 and 2024 financial years. At year-end, many institutional investors cast an eye over the market’s trash to find some treasure to drive portfolio returns in the coming year. Invariably, several bottom-performing stocks will confound market expectations and stage remarkable comebacks! In this piece, we will examine the “Dogs of the ASX” in FY 2025, sifting through the market’s trash to find treasure, and assess how the 2024 Dogs performed. We will also rate Atlas’ picks from 12 months ago. |

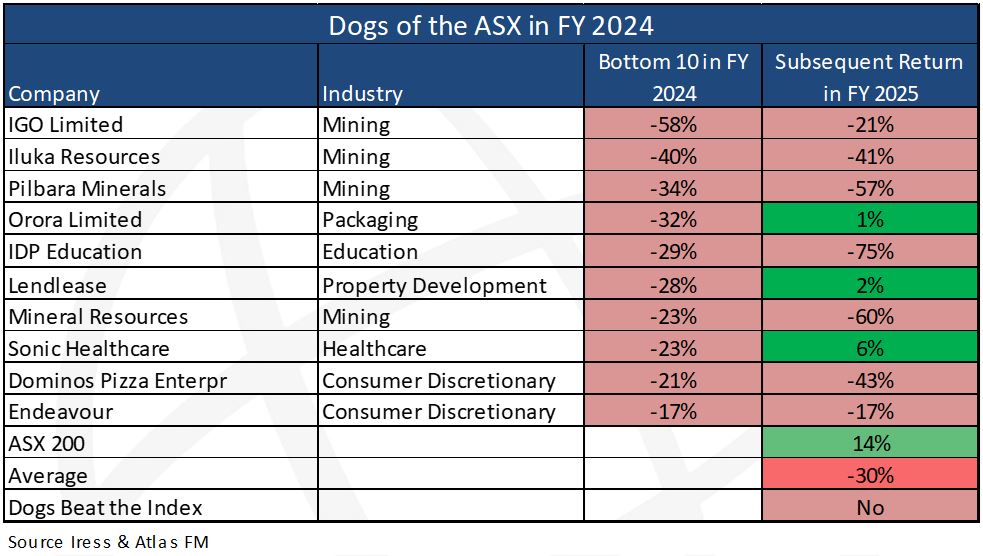

| The Theory Behind the Dogs of the Dow Michael O’Higgins popularised a systematic investment strategy of investing in underperforming companies named “Dogs of the Dow” in his 1991 book Beating the Dow. This approach seeks to invest like that of deep value and contrarian investors. O’Higgins advocated buying the ten worst-performing stocks from the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) over the past 12 months at the beginning of the year, but restricting the selection to those still paying a dividend. Restricting the investment universe to a large capitalisation index, such as the DJIA or ASX Top 100, improves the unloved company’s chances of recovery in the following year. Larger companies are more likely to have the financial strength and assets to sell, as well as an understanding of capital providers (such as existing shareholders and banks) that can provide additional capital to allow the company to recover from corporate missteps or unfriendly economic conditions. For example, over the past year, Mineral Resources bought some breathing room by selling its oil and gas leases to Gina Reinhart for $1.1 billion. Furthermore, larger companies tend to have more options when it comes to lenders, with the same embattled resource company having the majority of its debt on “covenant lite” fixed-rate US bonds. A smaller company is more likely to have its debt held by domestic banks in short-dated facilities, with local banks being more likely to move quickly to recover a doubtful debt, which can have adverse consequences for equity holders. Retail Investors Have an Advantage One of the reasons this strategy persists is that institutional fund managers often report their portfolios’ contents to asset consultants as part of their annual reviews. This process incentivises fund managers to sell the “dogs” in their portfolio towards the end of the year as part of “window dressing” their portfolio before being evaluated. Institutional fund manager selling of underperformers is especially prevalent in December and June of every year. The past year unusually did not provide any great examples of Dogs staging great recoveries, but in July 2022 a fund manager would have been having to vigorously defend why they owned Xero in their portfolio after had fallen -19% in the previous year (Xero’s share price rose +55% in the next 12 months). Similarly, in July 2023, owning contractor Downer EDI would have been a bold move after falling victim to accounting irregularities (gained +16% in FY 2024). Retail investors can afford to take a longer-term view on the investment merits of any company that may have hit a speed bump, as they are not swayed by asset consultants questioning short-term underperformance. Additionally, many underperformers see tax-loss selling around the financial year’s end, further depressing share prices in June. Often, the share prices of these underperformers rebound in the new financial year when this tax loss selling finishes and investors repurchase their shares. This is likely to be a bigger factor in 2025, with many investors looking to offset often very large capital gains realised by trimming CBA by selling poor performers from the past year. Dogs of the ASX in 2025 Over the past year, the Dogs from 2024 fell 30% and underperformed the ASX 200, marking the largest underperformance of the Dogs Portfolio since Atlas began analysing the series in 2011. Notably, in 2025, the “Dogs” contained no significant outperformers. |

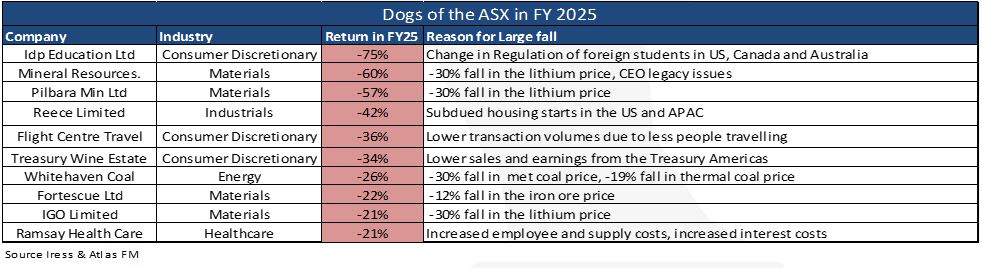

| From the table above, not one of the ten “dogs” of 2024 outperformed the index; this is the first time this has happened since 2010. The pain continued for lithium miners, including Pilbara Minerals, IGO, and Mineral Resources, following further declines in commodity prices and mine shutdowns. Mineral sands producer Iluka faced the challenge of rising costs, production issues and weaker Chinese demand for zircon. The pain continued in FY25 for former high flyers and favoured “growth” stocks, Domino’s Pizza and IDP Education. Domino’s announced that it was closing stores in Japan, Europe, and Australia. However, the broader market was concerned about declining same-store sales, as consumers focused on healthier options rather than just price and portion size. IDP Education had another rough year, with its share price now down 90% from its 2021 peak. University student placements and associated English-language testing volumes were impacted by restrictive international student policies in their key markets, including Australia, Canada, and the USA. The company is in a challenging position, as it has limited influence over government regulations regarding immigration policy. Endeavour has continued to underperform in 2025 due to slower retail alcohol sales and tighter regulations around its gaming machines, a high-margin hotel business segment. Our Picks From July 2024?? When making our picks twelve months ago as to which of the Dogs from FY 2024 would rebound over the coming year, Atlas’ class mark would be a “pass on a technicality”, probably a C+. We declined to pick a recovery in the lithium price due to the lack of owning a crystal ball. Similarly, Atlas did not select Domino’s to recover due to our lack of familiarity with the pizza markets in Japan, France, and Taiwan, as well as the associated costs of store closures. Similarly, in July 2024, we were cautious towards IDP Education after the Australian government increased international visa fees by 125%. However, we did not identify any further adverse factors impacting the stock, such as UK student visa restrictions and the Trump administration’s attempt to block Harvard from enrolling international students. In July 2024, Atlas picked Lend Lease (+2%) and Sonic Healthcare (+6%) to stage recoveries in FY 2025. Although this technically occurred, and these two were the best-performing Dogs of the ASX in FY 2024, both of their share price gains underperformed the ASX 200’s return. What Does the Class of 2025 Look Like? Looking through the list of 2025 underperformers, there are both some new and old faces on the list. IDP Education, Mineral Resources, Pilbara and IGO back up from FY2024, much to the chagrin of their shareholders. The key themes in the list of Dogs for the financial year 2025 are: 1. Commodity Prices – IGO, Pilbara Minerals, Fortescue, Whitehaven and Mineral Resources 2. Weaker consumer demand for non-essentials – Flight Centre, Reece and Treasury Wine 3. Adverse Government Regulation – IDP Education and Treasury Wine |

| Our Picks For FY 2026 In almost every year (except for last year), three or four companies in the Dogs of the ASX list will significantly outperform the market over the following year. Recency bias leads most investors to put too much emphasis on recent negative news and extrapolate this into the future, creating an investment case that the current unfavourable market conditions or poor management decisions will continue indefinitely. As always in selecting a share price recovery candidate for the next year, we generally look at companies whose current woes are company-specific rather than caused by factors outside the control of their management team, such as falling commodity prices or adverse government policies. Atlas’s picks for a recovery in the next 12 months are Mineral Resources and Whitehaven Coal. While both companies have been exposed to falling commodity prices that are beyond management’s control, both companies also possess near-term catalysts within management’s control that should see their share prices re-rate. The completion of the resurfacing of Mineral Resources Onslow iron ore haulage road is scheduled for September 2025. This will enable the company to move towards achieving its nameplate capacity of 35 million tonnes and start reducing its debt load. While management cannot influence global lithium prices, they can resurface a road. We see that FY2026 looks brighter for Whitehaven Coal after management has made a number of good moves over the past year. In March, the company sold down 30% of the recently acquired Blackwater metallurgical coal mine to customers Nippon Steel and JFE Steel, and has taken costs out of the formerly BHP-owned asset. A move that leaves the company effectively debt-free and paves the way for Whitehaven to lift dividends in August. Additionally, Whitehaven have recently started on an on-market share buy-back. |