The last four years have been very eventful for bank shareholders, with each year bringing a new set of worries predicted to bring the banks to their knees. 2020 saw capital raisings from NAB and Westpac missing their first dividend since the banking crisis of 1893, as experts forecasted 30% declines in house prices and 12% unemployment! Then 2021 saw the banks grappling with zero interest rates and APRA warning management teams about the systems issues they may face from zero or negative market interest rates, an issue that seems quite comical now. 2022 saw the RBA raise the cash rate from 0.10% to 3.10%, the most rapid tightening ever from Australia’s central bank. In 2023, the concerns have switched to the impact of sharply rising interest rates on bad debts and the upcoming “fixed rate cliff” expected to mostly roll-off by September 2023.

While the banks will surely see rising bad debts over the next year, Atlas views that the market is far too negative towards the banks in 2023, with bad debts being more moderate than during the GFC. In this week’s piece, we will look at how the banks are better placed to weather 2023 and 2024 than in 2007 to deal with the last rate tightening cycle.

Bad Debts will rise, but that is not bad

Rising interest rates will see declining discretionary retail spending as more income is directed towards servicing interest costs. While bad debts will increase, this should be expected. In the 2022 financial year, the major banks reported bad debt expenses between 0% and 0.2%, the lowest in history and clearly unsustainable. Excluding the property crash of 1991, bad debt charges through the cycle have averaged 0.3% of gross bank loans for the major banks, with NAB and ANZ reporting higher bad debts than Westpac and CBA due to their greater exposure to corporate lending.

In predicting the trajectory of bad debts in 2024, the 1989-93 spike in bad debts should be excluded, as bank bad debts spiked due to a combination of poor lending practices and very high-interest rates. Indeed in 1991, the head office of Westpac was unaware that different arms of the bank were simultaneously lending to 1980s entrepreneurs such as Bond and Skase et al., which resulted in the risk department grossly underestimating their exposure to these highly geared entrepreneurs. This saw in 1991 and 1992, bad debts hit 1.65% and 2.43% of loans (three times the peak of the GFC).

During this period, borrowers saw interest rates approaching 20% and unemployment at 11%, levels outside any current forecasts. Interestingly house prices only fell 10% in Melbourne and 9% in Sydney between 1989 and 1991.

2007 vs 2003

Back to Basics

Today the composition of Australian bank loan books is considerably different to what they were in the early 1990s or even 2007, with fewer corporate loans (such as to ABC Learning, Allco, and MFS) and a greater focus on mortgage lending, which is secured against assets and historically has very low loan losses.

Further, the major banks have pulled the plug on their foreign adventures, with no exposure to northern England and Asia that in 2008 saw high bad debts, often due to making questionable loans outside of the core market. Indeed in 2009, NAB recorded a bad debt charge of $3.8 billion, 25% of which came from the bank’s UK operations.

More Cheaper Capital

In 2023 all banks have a core Tier 1 capital ratio above the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) ‘unquestionably strong’ benchmark of 10.5%. This allowed Australia’s banks to enter the 2022/23 rising rate cycle with a greater ability to withstand an external shock than in 2007 going into the GFC, where their Tier 1 Capital ratios were around 6%. For investors, this means that the banks have more capital backing their loans. Additionally, the quality of the loan books of the major banks is higher in 2023 than in 2007 or 1991, which saw a greater weighting to corporate loans with higher loss levels than mortgages. Further, the banks’ funding source is more stable today than it was 13 years ago, with an average of 75% of loan books funded internally via customer deposits. This means that the banks rely less on raising capital on the wholesale money markets (typically in the USA and Europe) to fund their lending.

Stronger Employment

The major banks face the next few years in a far stronger position than they went into 2007. The unemployment rate is 3.5%, significantly less than it was going into the last rate tightening cycle. While rising interest rates will undoubtedly cause stress to many borrowers over the next 12 months, so long as employment remains strong, mortgage repayments will remain high and bank bad debts low. However, we expect the outlook for consumer discretionary stocks such as Flight Centre, Harvey Norman and AP Eagers to deteriorate as spending on Bali holidays, televisions and new cars is diverted to service higher mortgage payments.

More Market Share

Since the GFC, the banking oligopoly in Australia has only become stronger, with foreign banks such as Citigroup exiting the market and smaller banks such as St George, Bankwest, and now Suncorp being taken over by the major banks. While our political masters bemoan the concentrated banking market structure, having a strong, well-capitalised banking sector looked to be very desirable in March with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in the USA and in the wake of UBS’ forced takeover of Credit Suisse.

New Source of Demand

With the standard variable mortgage rate increasing from an all-time low of 2.14% in November 2020 to over 6% today, one would have expected significant falls in house prices, though this has not occurred. According to the latest CoreLogic Home Value Index, house prices, after falling in late 2022 and early 2023, have now been rising in April and May. Record net migration in 2022 (catching up post Covid) and with 2023 shaping up to be a strong year is surely contributing to both strength in house prices and surprisingly robust retail sales. Furthermore, the high proportion of skilled migrants in the intakes for 2022 and 2023 will likely introduce individuals into the Australian economy with a job waiting for them wanting to buy an apartment or house and consume goods and services.

For bank investors, stronger-than-expected house prices and general economic conditions will result in a more benign bad debt cycle with bad debts far lower than in 2008-2009 and nothing like 1990-92.

Our Take

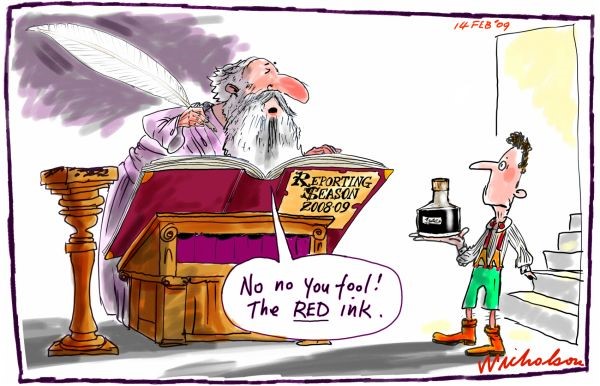

The May reporting season show that Australia’s banks are in good shape and face a better outlook than many sectors of the Australian market and increased dividends by an average of 17%. While the outlook for the banks remains far from certain, Australia’s banks have historically been very adept at maintaining profits throughout the cycle and, as discussed above, regularly adapting to deal with challenges to the banking oligopoly.

We expect the banks to outperform pessimistic market predictions over the next year, benefiting from higher interest rates and high employment levels, which will see customers tighten their belts to make the new higher loan repayments. While mortgage rate increases are unpleasant for many borrowers and will see declining consumer discretionary spending, we see that the spike in bad debts for the banks will be much less than the market expects, far lower than during the GFC or the recession of the early 1990s.