“Things are never as good as they seem or as bad as they seem“

Legendary investor Sir John Templeton

Last week the ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) released the Australian unemployment rate for February 2021, which surprised the market, coming in at 5.8% with 88,700 new jobs added since January. This positive news caused us to reflect on where we were a mere 12 months ago and the journey that the economy and equity markets have made from the depths of despair prevailing on this day twelve months ago; 23rd March 2020.

Panic Stations March 2020

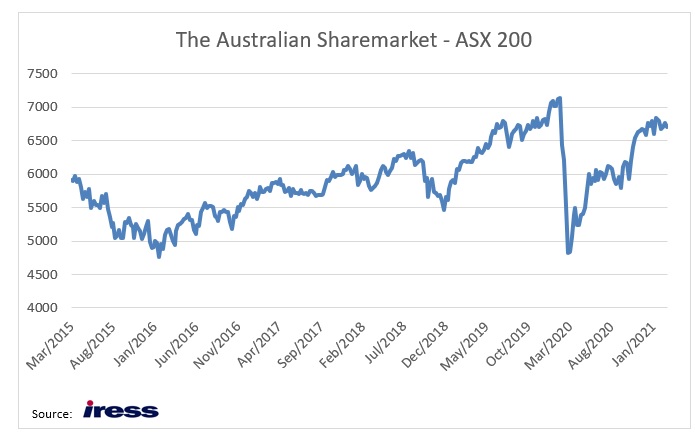

Twelve months ago, today, the ASX 200 fell -5.6% to 4546 with $11 billion worth of shares traded, making this day one of the top 20 busiest days in ASX history. The Australian dollar had crashed to an 18-year low of 57c, oil was at US$22 a barrel, and earlier on in the week, the RBA announced an emergency 25 point cut to interest rates. More alarming for investors were headlines predicting a severe recession with many businesses going into receivership and unemployment to reach levels last seen in the early 1990s or the 1930s. In the USA, a Federal Reserve Governor predicted that the US unemployment rate would hit 30% due to shutdowns to contain the virus and the US Congress failed to pass a $1 trillion Covid-19 aid plan.

Questions were being asked about whether commercial real estate and infrastructure would become stranded assets, as Covid-19 was likely to permanently change human behaviour, negating the need for offices, shopping centres and toll roads.

How the crash was different

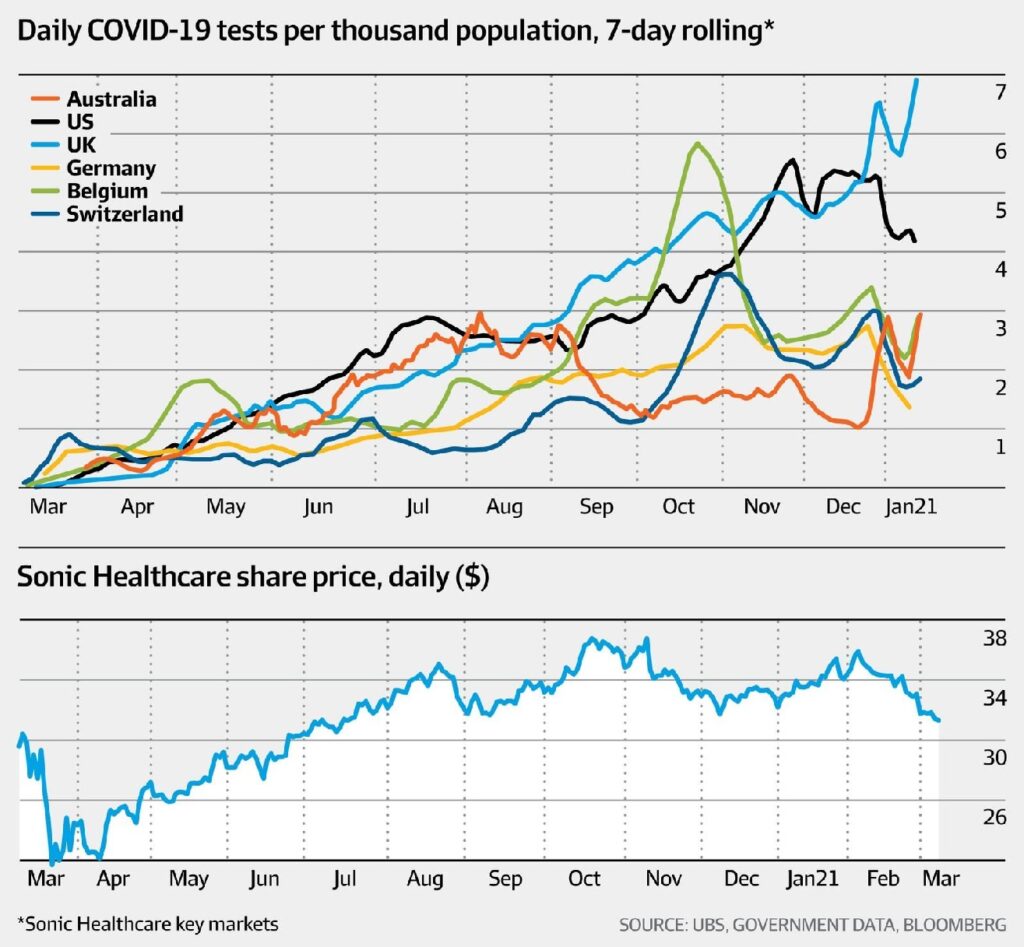

The crash in March 2020 differed from previous market crashes of 2000 and 2008/09 in that virtually the entire ASX was sold down heavily, even companies that were expected to do well during Covid-19 shut-ins. Atlas viewed that this selling pattern occurred due to the increasing influence of index funds and geared index funds on the stock market. When these funds received redemption, the manager mechanically sells shares in every company in the ASX 200 following its index weight. This saw sharp falls in the share prices in March 2020, even for companies such as JB Hi-Fi, Wesfarmers, Sonic Healthcare and Amcor that were likely beneficiaries from lock-downs and increased testing. Indeed, on this day 12 months ago, JB Hi-Fi revealed that March quarter sales had surged by +9%; nevertheless, their share price fell -11% to $24.61 on market capitulation.

The Banks

The banks were viewed as the canary in the coal mine and were expected to wear heavy loan losses from rising bad debts. For the following year, Westpac forecasted an 8% contraction in GDP, unemployment at close to 9% and house prices to fall 20% by the end of 2021. Consequently, bank shareholders felt the heat as dividends were either cancelled or suspended. While ANZ, Westpac and NAB cut their dividends during the Great Depression, both World Wars, the 1991 recession, and the GFC; one had to look back to the banking crisis of the 1890s to see the last time that major banks declined to pay dividends to shareholders, as was done in early 2020.

The path back March 2021

While it would be premature to declare victory over Covid-19, none of the doomsday predictions made twelve months ago has come to fruition, and any decision made in March 2020 to panic and liquidate equity portfolios would have been a poor one for investors. Indeed, 23rd March 2020 marked the bottom for equity markets globally.

Previous downturns such as 1982/83, 1992 and 2009 were quite different from what we saw in 2020. While in 2020, unemployment spiked and the stock market crashed in March and April, the levels of fiscal stimulus are much more significant. The Rudd Government’s $42 billion stimulus packages from 2008/09 were dwarfed by the $257 billion in direct Covid-19 related support measures. Moreover, Australia has seen very low to no community transmission of Covid-19, which has allowed the economy to function with fewer impediments than experienced in Europe and North America.

The recently completed February 2021 reporting season has seen companies outperform expectations on revenue, earnings and dividends. Earnings upgrades came from banks (with fewer bad debts) and resources (higher commodity prices). Dividends were the highlight of the reporting season, with many companies increasing payouts to shareholders, potentially recognising that dividends were cut too hard in 2020. Currently, the ASX 200 is a mere 5% below the highs set in February 2020, unemployment has declined from a peak of 7.5% in July 2020 to 5.8%, and retail sales are above pre-Covid 19 levels.

Finally, as following house prices is the one sport that unites all Australians, far from falling 20%, the most recent CoreLogic RP house price index showed that house prices were up +3% over the past year led by Sydney and Brisbane. Stable to rising house prices have seen bad debts for the banks significantly below expectations and seen rising capital ratios. This paves the way for higher dividends throughout 2021 and even bank share buy-backs, a scenario unthinkable a mere 12 months ago!

Our Take

I have had the “fortunate” experience of having observed three major crashes; March 2020, the GFC in 2007-08 and the Tech wreck in North America in 2001 from the front lines.During these dark periods, the portfolios were populated with companies paying dividends from stable recurring earnings such as TransCanada Pipelines and Amcor, with no exposure to companies reliant on the previous frothy market conditions Pets.com, Nortel, Babcock & Brown or Allco Finance.

What I learned from these experiences is that a portfolio constructed in a conservative manner populated by companies paying stable dividends with low gearing will bounce back from the blackest nights of doom and gloom. Additionally, as markets are driven by human emotions, at the period of maximum despair (March 2020), many investors make irrational decisions based on the view that share prices now only go down. Panic conditions on share markets can result in profitable investment opportunities for those that can avoid the noise. However, it is much easier to make this statement with the benefit of hindsight after the doomsday scenarios for the economy and corporate profits have not eventuated.