Iron ore, interest rates and banking relief – the ASX’s record cocktail

Normal text size Larger text size Very large text size A cocktail of ultra-low interest rates, high iron ore prices and a stabilising housing market has pushed Australia’s sharemarket to a new record high, surpassing levels last seen before the carnage of the global financial crisis.

Category: Uncategorized

Dogs of the ASX from FY’19

Over the past week most parents around Australia including myself have been receiving report cards from the children’s teachers; either confirming expectations as to how their offspring have performed in the classroom and exams or receiving some rude shocks about their child’s performances.

Similarly, fund managers around Australia have been writing reports

detailing how both their funds and the market have performed in 2019

financial year, and are both evaluating positions that performed poorly

in 2019 and looking for undervalued companies among last year’s

underperformers.

Unloved Mutts

The “Dogs of the Dow” is an investment strategy made famous by O’Higgins in his 1991 book “Beating the Dow” and seeks to invest in the same manner as deep value, and contrarian investors do. Namely, invest in companies that are currently being ignored or even hated by the market; but because they are included in a large capitalisation index and paying a dividend like the DJIA or ASX 100, these companies are unlikely to be permanently broken.

Inclusion in a large capitalisation index such as the ASX100 indicates that the unloved company may have the financial strength or understanding capital providers (such as existing shareholders and banks) that can provide additional capital to allow the company to recover over time.

Additionally, if it is still paying a distribution, the company’s business model is unlikely to be permanently broken, as the company’s directors are unlikely to authorise a dividend if insolvency is imminent. Smaller companies tend to face a harder road to recovery with a greater chance on insolvency when they make it onto the “Dogs” list.

Dogs of FY18 outperformed the market by 10% in FY19

Investing in an equal weighted portfolio of the dogs from 2018 would have resulted in an investor outperforming the ASX200 by 10% as the stellar gains from Magellan, Telstra and Ramsay more than offset the falls in Challenger, Pendal and AMP.

One of the reasons why this strategy has worked over time is that institutional investors often report the contents of their portfolios to asset consultants as part of annual reviews of the fund manager. This process incentivises fund managers to sell the “dogs” in their portfolio towards the end of the year, as part of “window dressing” their portfolio thus avoiding having to explain last July why they owned Telstra or QBE Insurance.

Dogs of the ASX over the 2019 Financial Year

The table below shows the bottom ten performing stocks ASX 100 stocks over the past twelve months and there will undoubtedly be some fallen angels that will outperform in the 2020 financial year. Looking through this the key themes are companies exposed to declining interest rates and the UK economy.

Rabid hounds best avoided…

AMP has had the dubious distinction of appearing on consecutive lists as Telstra did in 2017 and 2018, which could indicate that the embattled fund manager could be in line for a spectacular bounce in the share price as Telstra enjoyed over the past twelve months. However, as AMP’s new CEO is yet to unveil his strategy for the wealth manager which will undoubtedly involve some expensive restructuring and outflows continue to accelerate; it is difficult to make a case to adopt this hound into a portfolio.

It would be unfair to describe Challenger as a rabid hound, as a significant portion of their earnings decline is due to dramatically falling interest rates, a factor that is outside management control. Over the next year it is hard to see an improvement in investment yields, profit margins and annuity sales, but with the Japanese insurance giant MS&AD Insurance Group owning 16% of Challenger further falls in the share price may stimulate a takeover offer.

Rescued pooches just in need of a good home

Unibal-Rodamco-Westfield has gone from the penthouse in December 2017 to the doghouse in June 2019, as Westfield was taken over by the Franco-Dutch Unibal-Rodamco. The movement in the primary listing from the ASX to Paris and left shareholders with interests in unfamiliar assets such as Parisian Offices and shopping centres in Germany as well as exposure to French transaction taxes. While in Australia the news coming out of Europe often seems grim, Unibal’s flagship portfolio of shopping centres has continued to significantly outperform retail sales in key markets such as France and the UK. With this unloved global property trust trading on a forward PE of 11 times and a distribution yield of 8%, investors certainly have a margin of safety compared with other comparable investments listed on the ASX.

Flight Centre’s share price has suffered over the past year as falling house prices and an election have damped Australian consumer confidence and thus the appetite for leisure travel. However, looking ahead the skies don’t look as dark for Flight Centre. Since Flight Centre downgraded earnings in late April, we have seen the two cuts in interest rates and the passing of a tax package by the Coalition government. Stage one of the tax package which is backdated to July 1 last year, will more than double the end-of-year rebate for low and middle-income earners, from $530 to $1080 and should see Flight Centre book a few more holiday packages to Bali and the Gold Coast over the next year.

After enjoying several years of solid returns Lend Lease has been in the kennel in 2019 courtesy of a surprise downgrade in November 2018 courtesy of cost blow out in the company’s engineering business due to issues with Sydney’s NorthConnex tunnel. While Lend Lease’s funds management and global residential development businesses continue to perform well, an exit from the company’s volatile engineering business could see a significant rebound in the share price over 2020.

Our Take

With the ASX 200 up 21% in 2019 and the market looking fully valued, we see that it makes sense to go searching for some treasure amongst the market’s trash.

Here retail investors can have an advantage over institutional investors, picking up companies whose share prices have been under pressure and can take a longer-term view on the investment merits of a particular company that may have hit a speed bump without the spectre of losing investment mandate or consultant ratings.

ASX Half-Year Report Card

The ASX First semester Report Card, While the past week parents around Australia have been receiving report cards from the children’s teachers, mostly confirming expectations as to how their offspring have

June Monthly Newsletter Atlas High Income Property Fund

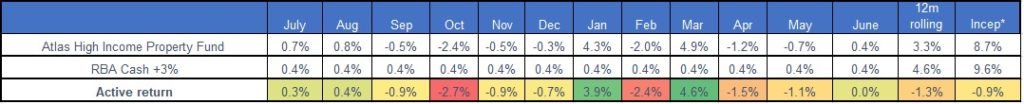

- The Atlas High Income Property Fund gained by 0.4% over June in an eventful period which saw Property Trusts raise close to $1.8 billion from investors, a sure sign that the market is getting fully valued, especially as most of these raisings were done at a premium to net tangible assets per share. Following the investing adage of “Be fearful when others are greedy”, we were active sellers over the month.

- The key news in June was the RBA cutting the cash rate to 1.25% which was a historic low and eclipsed previous low of 1.5% from October 1934. For almost a decade, the risk-free interest rate as measured by the Commonwealth Government 10-year bond yield has been relatively stable between 4% and 3%; however, in 2019, the risk-free rate has collapsed halving to 1.25%. This dramatic and unprecedented fall in the interest rate has put downward pressure on the premiums the Fund receives for selling call options. This is due to what in mathematical finance is referred to as the option “Greek” term called rho, which measures the change in the price of the option relative to the risk-free rate.

- In June we issued a new Product Disclosure statement for the Fund which can be accessed by clicking on this link.

Go to Monthly Newsletters for a more detailed discussion of the listed property market and the fund’s strategy going into 2020.