The “Dogs of the Dow” is an investment strategy that is based on buying the ten worst performing stocks over the past 12 months from the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) at the beginning of the year but restricting the stocks selected to those that are still paying a dividend. The thought process behind requiring a company to pay a dividend is that if it is still paying a distribution, its business model is unlikely to be permanently broken. The strategy then holds these ten stocks over the calendar year and sells them stocks at the end of December. The process then restarts, buying the ten worst performers from the year that has just finished. In this area, retail investors can have an advantage over institutional investors, many of whom sell the “dogs” in their portfolio towards the end of the year as part of “window dressing” their portfolio. Selling the worst performing companies avoids the manager having to explain to asset consultants why these unloved stocks are still in their portfolios.

In this week’s piece, we are going to look at the “dogs” of the ASX, focusing on large capitalisation Australian companies with falling share prices. Additionally, we are going to sift through the trash of 2018 to try to discern any fallen angels with the potential to outperform in 2019.

Unloved Mutts

The Dogs of the Dow was made famous by O’Higgins in his 1991 book “Beating the Dow” and seeks to invest in the same manner as deep value, and contrarian investors do. Namely, invest in companies that are currently being ignored or even hated by the market; but because they are included in a large capitalisation index like the DJIA or ASX 100, these companies are unlikely to be permanently broken. Inclusion in a large capitalisation index such as the ASX100 indicates that the unloved company may have the financial strength or understanding capital providers (such as existing shareholders and banks) that can provide additional capital to allow the company to recover over time. Smaller companies tend to face a harder road to recovery with a greater chance on insolvency when they make it onto the “Dogs” list.

Dogs over the Past Five Years

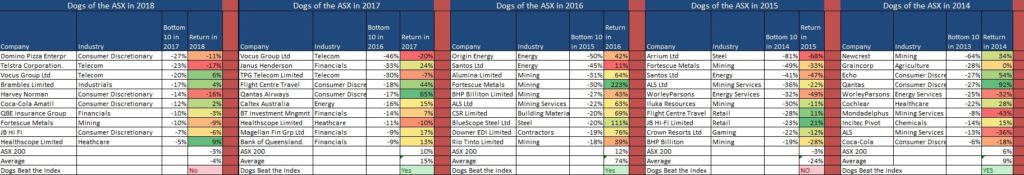

The table below looks at both the top and bottom performers for the past five calendar years and their performance over the subsequent 12 months. As always this is measured on a total return basis, which looks at the capital gain or loss after adding in dividends received. Whilst sifting through the trash at the end of the year yields the occasional gem – such as Healthscope in 2018 (+9%), Qantas in 2017 (+65%), Fortescue in 2016 (+223%), Qantas again in 2014 – an equal weighted portfolio of the dogs of the ASX 100 has outperformed the index in three of the past five years. In 2018 an equal-weighted portfolio of the “Dogs” effectively matched the ASX200, perhaps a fitting outcome for an unpleasant year for investors.

Themes

Looking at the above table, finding the fallen angel amongst the worst performers seems to work best where the underperformance is due to stock-specific problems, rather than macroeconomic issues beyond a company’s control. For example, Cochlear underperformed in 2013 after weaker sales as the company waited for approval to sell its new Nucleus 6 product in the United States. Subsequently, Cochlear’s share price has gained 202%, as hearing implant sales bounced back. Similarly, BlueScope steel had a tough 2015, which saw the company seeking government support to help restructure their Port Kemba steelworks. Concurrently, cheap Chinese steel took market share at the same time as key inputs of iron ore, and metallurgical coal was climbing upwards. 2016 saw a significant turnaround for BlueScope’s shares which gained +147% as profits recovered due to cost controls, stronger sales and the benefits of an acquisition in the United States.

Additionally, where the underperformance is due to a company-specific issue, the company in question may receive a takeover offer from a suitor that believes that they can snap up the company cheaply and then fix their problems. The best performing “Dog” from 2017 in 2018 was hospital owner Healthscope (+9%) that is now the subject of a bidding war.

The common factor among the underperformers that have continued their slide in the following year is when the underperformance is tied to factors outside the company’s control, such as a multi-year decline in a commodity. From the list of underperformers in 2014, continuing declines in iron ore delivered further pain to Arrium, Fortescue and BHP’s shareholders. Similarly, a several year

Unloved Hounds of 2018?

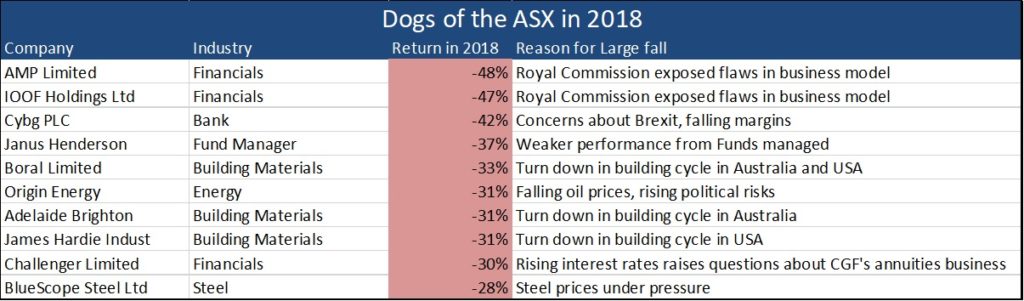

As a fund manager, the key question is whether there are potential show champions in the breed of unloved canines tabled below for the 2018 calendar year. Unlike previous years, the list for 2018 is more concentrated in a few sectors, reflecting industry-specific issues that have caused underperformance, rather than more easily fixed company-specific problems.

Looking at the two vertically integrated financial advisers AMP and IOOF, it is tough to see the near-term catalysts that will transform them into stars in 2019. The final report from the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry is due to be delivered in March 2019 and is not likely to be kind to these two companies. Similarly, the three building materials companies in the above table are unlikely to see a reversal of the trend of declining building approvals over the next twelve months.

Fund manager Janus Henderson could be poised for a turn-around in 2019, with an improvement in fund performance and further cost outs from the integration of the two funds management companies. As the company is trading on a PE of 7 times with a dividend yield of 7%, investors have a margin of safety. Similarly, a better than expected outcome from Brexit and an improvement in the acquired Virgin Money business could see NAB spin-off CYBG stage a come back in 2019.

Our View

While the Dogs of the Dow might work in a market populated with a diversified range of companies in uncorrelated industries such as McDonalds, 3M, Merck and Microsoft, it does not appear to be a broad strategy that one can use consistently in the ASX. We see that amongst the companies in the ASX 100, the composition of the index is not as broad as the Dow at an industry level. The ASX has a high weighting to resource companies, whose profitability is primarily tied to commodity prices (such as oil and iron ore) that are outside of management’s control and can be subject to multi-year declines. Similarly, the ASX has a high weighting to financials, all of which have suffered throughout 2018 from the Royal Commission.

Nevertheless, it can pay to sort through the dogs of the ASX. From the table above over the past five years, one of the top performers in the following year can be found by sifting through the dogs of the ASX100.