In the first instalment of Atlas’ surprisingly popular series on financial statement trickery written with the August reporting season in mind, we examined the three financial statements and some measures a company can take to “dress up” their financial results. In this week’s instalment, we will build on the previous earnings chicanery piece and look at some warning signs that there may be problems with a company’s financial statements.

Red Flag 1: the statements don’t match

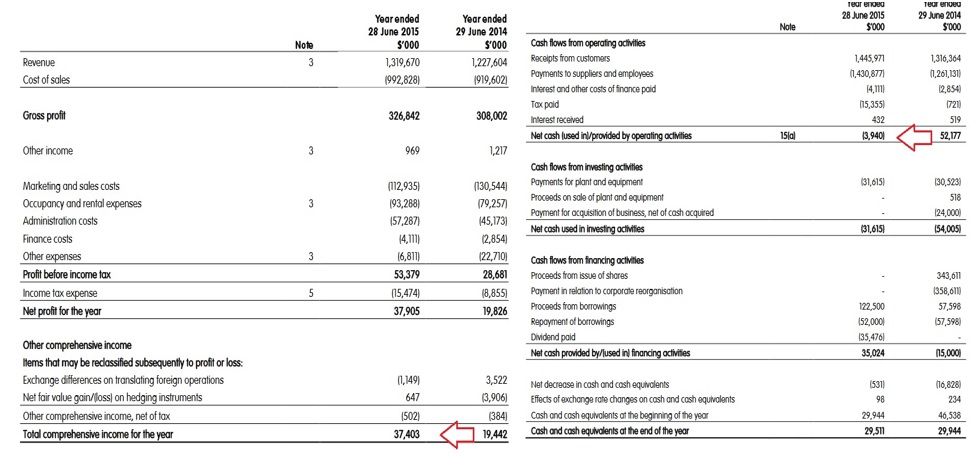

On results day, most attention is focused on a company’s profit and loss statement. In particular, analysts and the financial press scrutinise whether the company achieved the expected profit or earnings per share guidance, usually given at the last result or an update like the company’s annual general meeting three to four months ago. Whilst the profit and loss statement usually provides good guidance as to how the company’s business has performed over the past six months, as discussed last week, it is also the statement most open to manipulation and should be read in conjunction with the cash flow statement. When Atlas looks at a company’s reported profits, we compare them to the operating cash flow. If there is a big divergence, then the accounts should be looked at carefully.

The red flag we are looking for here is when a company’s cash flow and profit and loss statements are moving in different directions over an 18-month period and where a company is showing growing profitability but declining cash flows. In the table below from the 2015 accounts, electrical retailer Dick Smith Holdings reported income growing from $19 million to $38 million, greeted with applause, yet operating cash flow fell from $52 million to -$4 million. This suggests that the sales generating profits reported on the profit and loss statement were pushing the company towards administration, which happened the following year. Insolvency investigators found questionable management decisions, such as holding 12 years’ worth of sale as inventory in private-label AA batteries!

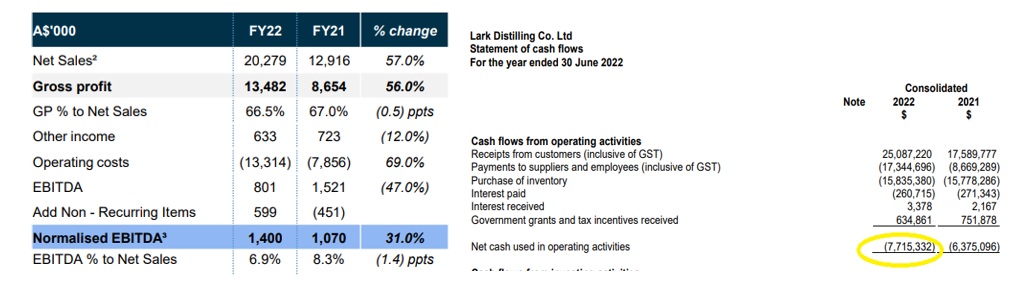

Another recent example of this can be seen in the producer of Atlas CIO’s favourite libation – Lark Distilling. Last year the whisky company reported robust profit growth and record annual sales. However, the cash flow statement painted a different picture, one of a company in negative cash flow requiring equity raisings to remain solvent. This appears to have continued in 2023, with the distiller of Tasmania’s finest seeing their cash balance fall from $16M to $7M.

We recognise that some of this is due to the working capital nightmare of whisky and wine production and cellaring, where costs of distilling, storing in oak barrels and taxes are incurred upfront and revenue collected many years later. However, in all businesses growing profits and increasing negative cash flows indicate profit-less growth and invariably result in dilutive equity raisings or worse.

Not always bad if the statements don’t match

Some businesses’ earnings on the profit and loss statement can diverge from the cash flow statement. For example, a construction company such as Lend Lease or Downer might not physically be paid until July of the following year for work done on a railway or apartment high rise, with significant costs and cash outflows incurring in the current period. Here the profits at a point in time may be greater than the cashflows, though the lumpiness of the cash flows received from large individual contracts should even out over time. Though Downer may not be the best example after being the poster child for accounting irregularities over the past year, slashing profit guidance and restating past years’ profits, overstated by $30-40 million.

Red Flag 2: A company consistently reports extraordinary items

Extraordinary items are gains or losses included on a company’s income statement from unusual or infrequent events. Importantly, they are excluded from a company’s operating earnings. These items are excluded from earnings to give investors a more “normalised” view of how the company has performed over the period. For example, if an industrial company such as Boral books a $50 million gain from selling excess industrial land, including this profit would obscure information about how the company’s building materials businesses have performed over the past six months.

While reporting extraordinary items can be valid and useful, investors should be wary or make adjustments to company earnings where a company has frequent (and almost always negative) extraordinary items they seek to exclude from their reported profits.

As a long-term observer of the Australian banks, almost every year, they put through a write-off of the software below the profit line. In my view, investing in banking software is a core part of their business model, and it seems curious that the institution is willing to take the productivity benefits in their normalised earnings whilst ignoring a portion of the costs needed to achieve these gains.

Red Flag 3: Significant divergence from comparable companies

The warning sign we are looking for here is when a company consistently has higher average profitability, revenue growth or better working capital management than their industry peers. Invariably when management is asked, they will give an answer that relates to management brilliance or superior controls. Still, realistically mature companies operating in the same industry tend to exhibit very similar characteristics. As such, their financial statements should, to some extent, correspond to the statements of companies operating in the same industry. For example, supermarkets such as Woolworths should have a similar cash conversion profile to Coles (operating cash flow divided by operating profits) and not dissimilar profit margins, as they are selling identical products to largely the same set of customers. Further, the major banks should exhibit similar bad debt charges on their mortgage books, though the overall bad debt charge could diverge if a particular bank was overly exposed to specific large corporate bankruptcies.

Hollow logs?

Occasionally management teams may be incentivised to under-report profits in any current period. This generally occurs when a company is under heightened union scrutiny due to wage negotiations with their employees, excessive government attention from perceived excessive profits, or expects a problem in the next year and wants to smooth their profits. For example, in the current environment of extremely low bad debts, a bank could be incentivised to boost its bad debt provisions aggressively. Increasing provisions would reduce current period profits, with excess provisions, if not required, could be written back later to boost future profits. This is potentially a politically astute move when politicians are getting extensive press coverage for calling out a company’s headline profits, as Commonwealth Bank found out on Wednesday; see AFR Corporate earnings’ obscene’ as CBA posts record profit, say Greens. What was ignored by politicians here was the divisor of 1.67 billion CBA shares on issue that saw earnings per share increase by only 8%.

Our Take

Earnings misrepresentation is difficult for investors to detect from the publicly available accounts, but when revealed can sometimes have extreme results for a company’s share prices. In my experience, this is more an art than a science, as the investor gets a sense that something is not right with the accounts rather than definitive proof of earnings manipulation. Normally actual manipulation generally only becomes obvious ex post facto after management has been removed or a company goes into administration.