Atlas’ default position on new IPOs (initial public offerings of new companies) is one of scepticism. However, occasionally a great IPO comes along – either for a long-term investment or one with a high probability of making a short-term gain on its opening day – so it is always worthwhile to run the ruler over companies about to list on the ASX.

In this week’s piece we are going to look at the seven

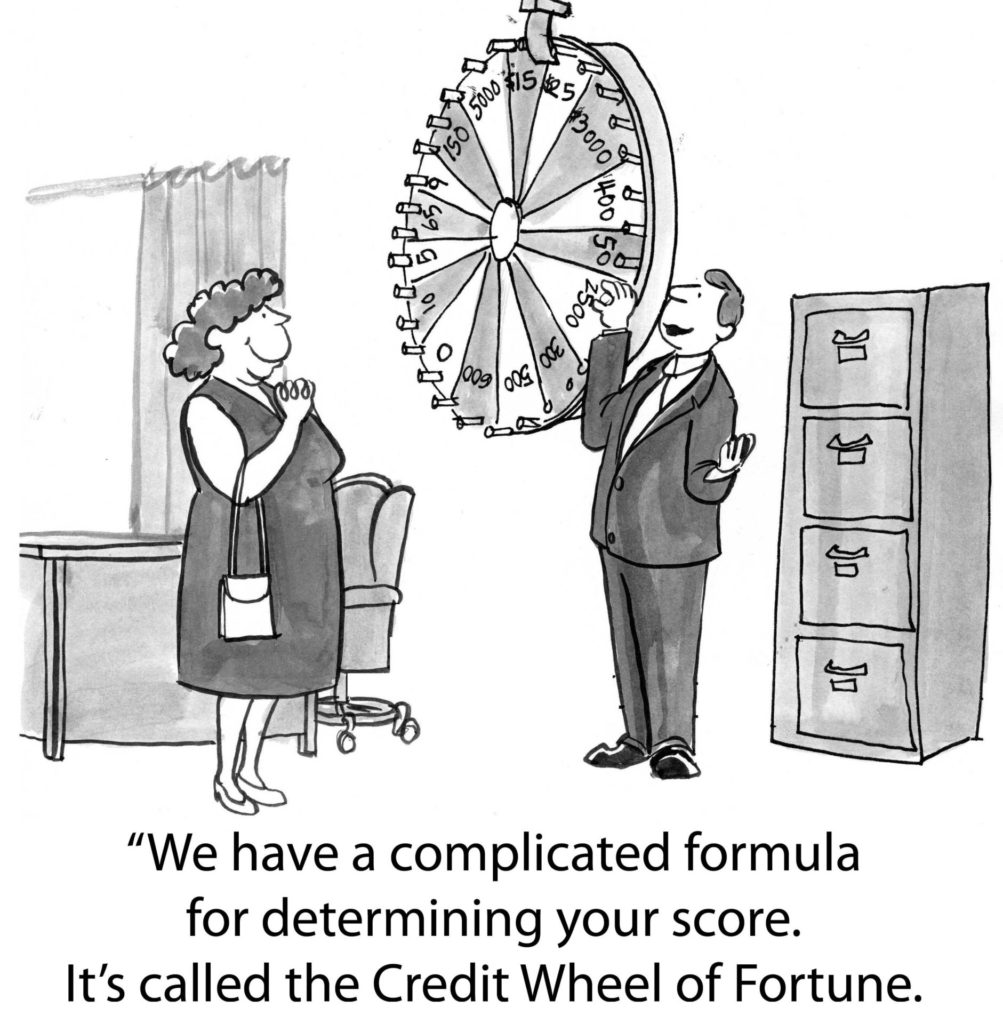

When analysing IPOs, few have been more eloquent on this subject that Benjamin Graham, the father of Value Investing:

“Our

recommendation is that all investors should be wary of new issues –

which usually mean, simply, that these should be subjected to careful

examination and unusually severe tests before they are purchased. There

are two reasons for this double caveat. The first is that new issues

have special salesmanship behind them, which calls therefore for a

special degree of sales resistance. The second is that most new issues

are sold under ‘favourable market conditions’ – which means favourable

for the sellers and consequently less favorable for the buyer”

[The Intelligent Investor (1949), Harper & Brothers: New York, p.80]

In the case of Latitude, we would expect that investors will be confronted with a high degree of salesmanship from the thirteen investment banks, stockbrokers and financial advisory groups that are all wetting their beaks based on how great a proportion of shares they can place, with $69 million of fees on offer. Given the large spread of investment banks participating in the Latitude IPO, potential investors are unlikely to see much critical research published about the company.

History

Latitude Financial (Latitude) is the rebranded GE Money which was acquired by the three private equity partners in 2015 (KKR, Värde Partners and Deutsche Bank). GE Money is a consumer finance business, offering products such Myer credit cards, car finance, Latitude branded credit cards and – importantly – point of sale finance at stores such as Harvey Norman, Apple and JB Hi-Fi. Latitude currently has a loan book of A$9 billion.

GE (General Electric) is a massive US conglomerate: it was one of the 12 founding companies listed on the Dow Jones Industrial Average in the year 1896. GE is best known for heavy engineering products such as power turbines and oil rigs, as well as household electrical items such as light bulbs. Consumer finance may seem like an unusual line of business for a company that makes offshore oil rigs. However, this business was essentially a capital arbitrage play based on GE’s strong balance sheet. GE Money was able to leverage off its parent company’s credit rating (previously AA) to borrow cheaply in the wholesale market, and as it not a bank, there is no deposit base.

In 2008 the business model of the GE subsidiary GE Capital was tested – and nearly failed. When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, GE Capital, like many financial companies, had to seek assistance from the US government since about a third of its funding was short term.

Can the business be readily understood?

Latitude’s business model is relatively simple: it lends money to customers at a higher rate than they pay to borrow it on the wholesale markets. The profit is the margin between what Latitude borrows and what it lends, less the costs of doing business which includes unrecoverable loan losses. Latitude’s customer base is typically a consumer who earns around $40,000 annually and who does not have a bank credit card.

Another way that Latitude makes money is by charging fees to merchants such as Harvey Norman to establish a loan where, for example, the merchant is offering an interest-free term on the sale of a TV. Latitude does well when the customer does not pay off the TV at the end of the 12-month interest-free period. In the example of a TV purchase at Harvey Norman, the balance owing is then charged interest of 29.49% as well as a monthly fee of $6. The average transaction size for Latitude is around $1,600, and the company has an average of 1.7% of their loan book over 90 days delinquency. By comparison, Commonwealth Bank reported in August that in their credit card division around 1% of their loan book was over 90 days in arrears.

Why is the vendor selling?

The motivation behind the IPO is one of the first things that potential investors should consider. Historically investors tend to do well where the IPO is a spin-off from a large company exiting a line of business, or the vendors are using the proceeds to expand their business.

While the owners floating a company may want to sell out completely, after the debacle of the 2009 Myer IPO – which saw the department store’s private equity owners sell their entire holding at listing – new investors are unlikely to accept a full exit without a substantially lower price (in terms of profit multiples). However, seeing private equity owners retaining an ownership stake after the float is no guarantee that the IPO will be a sure-fire winner. For example, the vendors of Dick Smith retained a 20% stake on listing, which was sold down nine months later. Within three years of the float, Dick Smith went into administration.

The proceeds of the Latitude IPO are being used to allow the owners (KKR, Värde Partners and Deutsche Bank) to cash out around $1.2 billion. Post the IPO these three will still own 54% of Latitude, and investors should expect a further sell-down in the future, with this stake in escrow until August 2020.

Furthermore, Latitude’s growth has been

Is the business profitable?

Yes. In 2019 Latitude is expected to deliver net profit after tax of $164 million, which is expected to grow by 8% in 2020. After analysing hundreds of IPOs over the years, it always pays to be wary of IPOs that promise big jumps in profitability just after listing, as this rarely occurs. Healthscope and Spotless both promised solid profit growth in the years after their IPOs and investors saw the share prices of both companies sold down heavily after the promised profit growth was not delivered. If a company were poised to deliver a jump in profit the year after the IPO, the vendors would have a strong incentive to wait another year before listing, as the higher annual profit would dramatically increase their exit price which is valued on a multiple of this profit.

Structural Concerns

Latitude’s principal sources of funding for the financing of its products comprise Australian warehouse trusts (60% of funding) and issuing asset-backed securities (ABS) (40% of funding). The warehouse facilities (which give Latitude the ability to borrow a certain amount from a group of banks for a certain period) are all very short term, with the three facilities expiring Sep 2020, Mar 2022 and Feb 2021. Latitude’s entire business model assumes that these warehouses will always be open and restocked at favourable rates by their banking partners. The assumption that the future looks like the past is what caused RAMS and Adelaide Bank a lot of trouble during the GFC when banks decided not to renew these warehouse facilities. Unlike the banks, Latitude does not have a base of retail deposits to finance their loan book.

Additionally, Latitude is exposed to Australian unemployment which is at its lowest level in the past 50 years. Rising unemployment will both increase Latitude’s bad debts and reduce ongoing revenue, as Latitude’s customers are likely to be unwilling to make further purchases. Additionally, Latitude is exposed to trends in consumer credit with millennials favouring AfterPay’s buy now pay later financing for online purchases over Latitude’s traditional business of a customer financing a TV in person at Harvey Norman.

How attractive is the price?

The upcoming Latitude IPO is for 35% of the company and shares are being offered at a price between $2 to $2.25. This will value the company between $3.5 and $4 billion on a market capitalisation basis. The price represents a profit multiple of between 12- and 14-times Latitude’s 2020 forecast cash profit and a dividend yield of around 5%. While this looks attractive, Latitude is being priced at a premium to established banks such as Westpac and NAB.

Our Take

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it sometimes rhymes. Going through the Latitude prospectus, there is a range of similarities to the RAMS prospectus 12 years ago: namely, a financial company built on arbitraging the difference between wholesale and retail interest rates that ultimately depends on the goodwill of banks to continue to lend to them. While the price multiple appears to be prima facie attractive, there are too many warning bells for Latitude to be included in the Atlas portfolios at the IPO. Additionally, with 65% of the register destined to be sold in 2020, it is hard to see Latitude’s share price having a sustained rally from the IPO price over the next year.

Finally, with the last line of Ben Graham’s perspective on IPOs in mind, given the movement in the coal price over the past few years, it is hard not to take the view that October 2019 may represent a very favourable time for Latitude’s owners to be selling shares to Australian investors.