Over the past few years, the press has been full of articles about tariffs and trade policy and seen politicians from Trump to Albanese trumpet the desire to relocate entire industries driven by tariff walls or massive taxpayer subsidies. Our elected leaders inevitably paint some utopia, with factories as far as the eye can see in a nation that is self-sufficient in the production of most goods. However, we have seen little analysis of the economic rationality of producing sneakers or jeans in the USA (replicating existing plants in South East Asia) or building a solar panel industry from scratch in Australia. This would see high-cost domestic production try to compete in a saturated market currently dominated by low-cost photovoltaic panels, generally made by experienced Chinese manufacturers who own the intellectual property.

Every country, even the USA, has a finite amount of resources that can be allocated to the production of goods and services, and it is not rational for a nation to produce goods where it has no competitive advantage. Indeed, the Australian car manufacturing industry enjoyed $7 billion of direct government subsidies from 2001 to 2017 in addition to tariffs on imported cars that were as high at 60% in the 1980s. Arguably, taxpayer funds could have generated greater utility being directed to hospitals or agriculture research, than propping up the production of cars that increasingly fewer Australians wanted to drive.

In this week’s piece, we are going to look at some of the greatest economists of all time and apply their thoughts as to why tariffs are a bad idea and why the USA should not produce sneakers nor Australian four-door hatchbacks.

Adam Smith’s (Father of Economics) Absolute Advantage and Specialisation:

Adam Smith was an 18th-century Scottish economist and philosopher who developed the economic theory of absolute advantage and specialisation amongst economies. An economy is said to have absolute advantages when it can produce goods at the lowest cost. The economy with the lowest cost of production could then export to other countries, bringing down the price in the importing country. This benefits everyone as the exporter makes money from exporting goods, and the importer lowers the cost of products in their economy. The original example used by the father of economics was England, which specialised in producing cloth in the mills of Manchester and Portugal, which specialised in wine. This is an example that reflects political tensions in 1776 with England’s traditional wine source, France.

Specialisation refers to a business or economy focusing on one or a few products in order to become more efficient and cheaper to produce those products. An example would be China setting up thousands of steel smelters across its nation, making it much cheaper to produce steel in China than in Australia. This specialisation caused BHP to stop smelting steel in Australia and just ship the iron ore to China, as it was much cheaper and more value-accruing in the long run for the company.

David Ricardo’s comparative advantage:

David Ricardo was a British Economist who was inspired by Adam Smith’s theory and developed his own theory that focused more on comparative advantages across economies. Here, he expanded on Adam Smith’s theories to account for a situation where a country had an absolute advantage in producing two goods, such as Portugal producing wine and cloth with fewer resources than England. Comparative advantage accounts for opportunity cost, something missed by Trump and Albanese in that this is the cost of foregoing another opportunity to create a particular good. For example, America could become the cheapest producer of steel or Australia in solar panels, but that would see capital (or more accurately, taxpayer subsidies) moved into lower productive industries rather than highly accretive industries such as technology and data centres or agriculture and mining in Australia.

How does this apply to bringing manufacturing back to the United States?

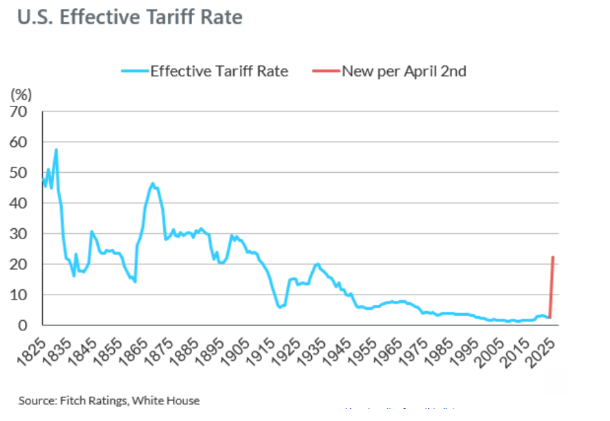

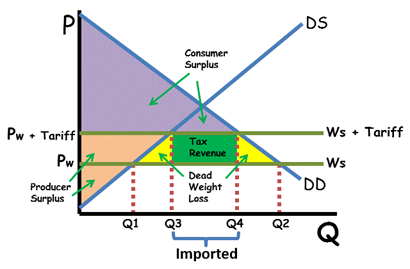

The main point of the two economic theories above is that specialisation and comparative advantage only work if there is free trade between economies. As seen in the graph below, introducing tariffs into an economy will increase the price of goods and services within the economy. This is partly offset by an increase in tax revenue but also creates dead weight loss (the yellow shaded area), which is economic loss due to market inefficiencies. Whilst this looks small in the graph, once applied across a whole economy, it will see a major slowdown in growth across the economy as well as increasing inflation from market inefficiencies.

By bringing manufacturing back to the United States, President Trump is encouraging the American workforce to move towards lower-paying and producing industries. Whilst they can have an absolute advantage in many of these manufacturing industries, they are forgoing the opportunity to invest in much more advanced areas that contribute more to the economy.

As for specialisation, the nations that Trump is trying to bring manufacturing back from (Vietnam, Cambodia, China) have specialised in these manufacturing procedures for years, with the best infrastructure in place to the point that they are the lowest-cost producers in the world.

Moving this manufacturing back to America will increase the unit cost of the products for consumers, as infrastructure and capital will need to be invested, adding to inflation. Tariffs are used to make these higher-cost American-made products more competitive in the marketplace by increasing the costs of international products entering the USA.

Our Take:

The past month has seen many market commentators dust off their old economics textbooks to research what tariffs are, and politicians simplistically assume that free trade is a zero-sum game that transfers wealth from one country to another. Ultimately, the biggest victim of Trump’s erratic trade policies will be his own constituency, which will raise inflation with far less tariff revenue raised than expected and fewer factories on-shored. Nike is as unlikely to start building new sneaker plants in Oregon, even in light of 125% tariffs, as American workers are to line up to man the glue guns.

While the past month has been unpleasant in terms of share price volatility, the Atlas Portfolio is populated with companies that will see minimal impact from Trump’s tariffs, with earnings and dividends for the six months ending June 2025 similar to what we expected during the February results season. The companies we own with operations in the USA sell goods and services to US consumers that rely on minimal imported products, with the rest of the Portfolio comprises companies such as banks, toll roads and insurers that service the domestic Australian market.