The business of wealth management has been put under the microscope over the past month with the Royal Commission into the financial services industry. In March, the Commission focused on misdeeds in consumer lending and for the next two weeks in April it will be concerned with transgressions around financial advice.

The Royal Commission has highlighted the extent to which the major financials are involved in the business of managing Australia’s investments. Consequently, this week we are going to have a closer look at the funds management landscape in Australia. In particular we will examine the degree of vertical integration by the largest players of this industry that looks after A$3.4 trillion of investments for Australians.

Influence of the Major Institutions

The wealth management businesses of Australia’s major financial institutions (Commonwealth Bank, NAB, ANZ Bank, Westpac, Macquarie Bank and AMP) include funds management, life insurance and general insurance, investment administration platforms, and financial advice. The wealth management business is attractive for the banks, not only due to the government mandated growth that comes from rising compulsory superannuation contributions, but also because wealth management earnings carry a low capital charge. This appeal only increased with the $19 billion of capital raised in 2015 to meet Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s (APRA) tougher stance on bank capital adequacy.

Whilst this might not be the most exciting of topics, changes to capital requirements have two important effects: they make funds management earnings more attractive to the banks, and also increase the cost of lending to business and home buyers. When a bank makes a standard home loan with a ~70% loan to value ratio (LVR), the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) requires that the bank hold approximately $2 in capital for every $100 lent. This rises to $5 for every $100 in the case of a loan to a business that incurs a higher risk weighting. Mathematically, when a bank is required to quarantine more capital to conduct activities, their return on equity (ROE) declines. This decline may not seem very significant, but in an environment in which the Australian banks are facing higher capital requirements from regulators globally, earnings from wealth management are very attractive as they can boost the bank’s return on equity. Additionally, participating in the government mandated growing superannuation pool is seen as attractive to the major banks, since growing superannuation balances are expected to have a limited correlation with the credit cycle and demand for loans.

Vertical Integration: Clipping the Ticket at every stage

Over the last twenty years the major financial institutions either bought, or have organically created at great expense, a financial supermarket. This was based on the Allfinanz or bancassurance model, that assumed the banks could efficiently deliver banking, insurance and funds management through their existing networks, with employed tellers and financial advisors cross-selling “home brand” financial products. Aspirations to this model enticed the Commonwealth Bank to acquire Colonial in 2000, National Australia Bank to buy MLC, and Westpac to purchase BT and Rothschild Wealth Management. Additionally, by buying downstream financial advice groups, the major financial institutions acquired a distribution network for the financial products they manufacture such as managed funds, loans and life insurance.

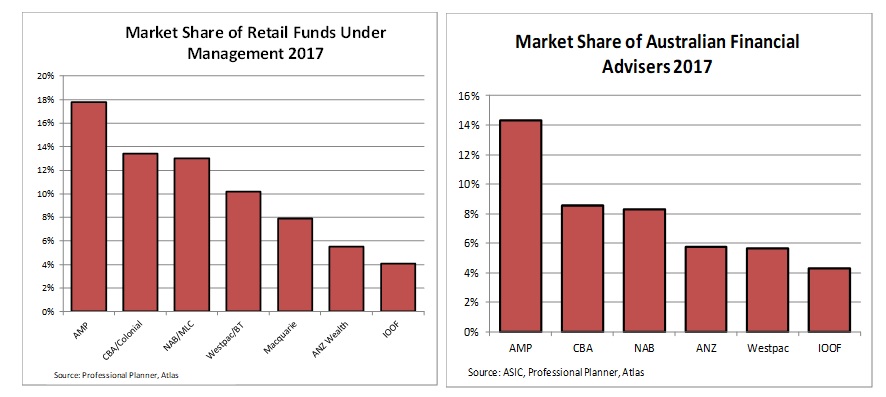

In essence, the wealth management industry comprises a value chain of advice (financial advisers), portfolio administration (platforms) and manufacturing (funds management). The major financial institutions have captured a dominant market share in all three links in the wealth management chain via acquisitions and IT expenditure. As shown in the below chart on the right, the four major banks plus AMP and IOOF have financial relationships with just under 50% of the financial planners in Australia. Their market share had been increasing with acquisitions (such as Count, acquired by CBA in 2011 for example) and heightened compliance requirements that tend to favour the large institutions over smaller practices. However, over the past two years we have seen a swing away from this trend with the number of independent financial advisers growing. One of the potential outcomes from the current Royal Commission is that investors will become increasingly aware of the conflicts of interest inherent in the vertical integration of wealth management, and management and will shift towards using independent financial advisers.

The major financial institutions have also been very successful in capturing a large share in the business of actually managing the money. The above chart on the left demonstrates the dominance that the large institutions enjoy in “manufacturing” the investment products, or funds for sale to retail investors. Currently the major banks plus AMP manage almost 80% of the retail funds under management, though this may change shortly with CBA looking at listing its funds management arm Colonial First State via an IPO. Westpac’s share of funds management is declining as the bank continues to reduce its ownership position in BT Investment Management.

Finally, investment platforms are the “middle man” in the process, connecting the fund manager to the adviser by providing administration services and tax reporting for a client’s portfolio of managed funds, shares and cash. Platforms generally charge around 0.3-0.6% of funds under management annually. Whilst running platforms might not sound like a very glamorous business, it has been a lucrative area for the major financial institutions, which by virtue of their IT expenditure have been able to capture over 85% of this market. However, like financial advice, the dominance that the major financial institutions have enjoyed on the platforms is being eroded by smaller more nimble platforms such as Hub24 (1. see below note), Netwealth and OneVue. These platforms have been very successful in capturing market share from the big banks due to a combination of accessibility and the flow of financial advisers leaving the major financial institutions.

Not all good news

At first glance, vertical integration sounds like a solid way for banks to supplement banking profits in an environment of relatively anemic credit growth, rising capital requirements and government mandated superannuation flows. However, the events of the past few weeks demonstrate that the ownership of wealth management businesses by the banks do pose some risks.

Aside from the volatility in investment returns, wealth management businesses have delivered adverse headlines that could impact on an institution’s core banking business. Over the past few weeks we have seen financial services CEOs face the Royal Commission due to allegedly fraudulent behaviour and bad financial advice from the banks financial planners. Indeed, we have also seen the Treasurer flag the possibility of gaol time for bankers!

In 2017 Commonwealth Bank spent $437 million in advertising to build its banking brand. While AMP does not disclose in its annual accounts what it spends annually on marketing, we would be surprised if it was less than $100 million. One would have to imagine that a portion of the goodwill that this spend generates has been dissipated by headlines detailing malfeasance in these institutions’ financial planning, platforms and insurance divisions. The management teams at the major financial institutions must be concerned that unethical behaviour observed in the wealth management businesses should not spill over to damage their core banking brands that generate the bulk of their profits.

1. Disclosure: in April Atlas in partnership with Maxim Private have launched the Maxim Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio on the Hub24 platform.

Our Take

The major financial players have not built these vertically integrated wealth platforms (comprising advice, investment accounting and funds management) to see large amounts of value being “leaked’’ to service providers outside the network. This naturally creates strong incentives to recommend the house products over independent providers, or to favour house products over external products with similar or even slightly superior characteristics. As an investor in the major banks, we would prefer that they keep as much of the value in-house to boost payments to shareholders, however as an independent boutique investment firm, we also have a strong personal incentive to see the vertical integration model break down and for clients to seek out independent financial advisors.

Whatever the composition of the market, of utmost importance is that all financial service providers adhere to rigorous codes of ethical conduct, such as that of the CFA Institute as the unethical behaviour revealed by the Royal Commission damages public trust in the financial industry as a whole.