In March Wesfarmers announced their intention to demerge Coles into a new separately listed company, with the new company expected to list on the ASX next Wednesday. Existing Wesfarmers shareholders will receive 1 share of Coles for every Wesfarmers share they own and the parent company will retain a 15% ownership stake in Coles. In this week’s piece, we are going to look at Coles, a new ASX Top 20 company that was last seen as a separately listed company 11 years ago.

As Wesfarmers shareholders, we have closely analysed the 400-page demerger document in an effort to understand how the new company will be structured. Additionally, unlike IPOs (initial public offerings) we like demergers because investing in the newly de-merged child company is frequently very profitable. See our piece Breaking Up. Unlike IPOs where private equity owners are frequently looking to maximise their exit price when a large company is spinning off one of their business units, they are incentivised to give the new company a solid, well-capitalised start with every chance of success. Obviously, when the parent company is giving shares in the new company to their existing shareholders, they don’t want the new company to fall flat on its face just after listing!

History

Coles started life as a single supermarket in Melbourne in 1914 and grew via organic expansion and acquisitions in the supermarket, department store (Kmart), and liquor retailing areas until the company was merged with Myer in 1985 to create Coles Myer. In the 2000s this sprawling retail empire underinvested in their retail offering and underperformed the resurgent Woolworths. This led to management selling the Myer department stores to private equity firm Newbridge in 2006, and Wesfarmers taking over Coles in 2007 in a cash and scrip takeover valued at $19.3 billion. During the last ten years, Wesfarmers have invested in Coles to rebuild their profit margins and improve efficiency to win market share back from Woolworths.

This demerged Coles is not the same as the 2007 version, as Wesfarmers have invested around $9 billion in the Coles business, growing the number of stores and their liquor business. Additionally, the Officeworks, Target and Kmart assets are remaining with Wesfarmers. Essentially the new Coles will comprise three major divisions:

- A full-service supermarket providing fresh food, groceries and general merchandise with 809 supermarkets throughout Australia (80% profits)

- Coles Express that operates 711 petrol station convenience stores under an alliance agreement with Viva Energy (10% profits)

- Coles Liquor, a liquor retailer with 899 stores under the Liquor land, First Choice Liquor and Vintage Cellars brands (10% profits).

Can the business be readily understood?

Yes. Unlike some companies on the ASX, Coles is a business that most Australians will interact with on a weekly basis. It employs around 112,000 Australians. As a retailer they order goods from wholesalers that are delivered to Coles’ distribution centres, these groceries and wine are then delivered to Coles’ supermarkets, convenience and liquor stores, to replace goods sold. Unlike consumer discretionary retailers such as Myer, consumer staples retailers don’t tend to get stuck with goods that have fallen out of fashion. Famously clothing retailer GAP had a downgrade a few years ago after over-estimating the demand for lime green and mustard yellow coloured leather coats.

How does it make money?

Coles is a high volume or revenue business with low-profit margins and a low return on capital. It operates in a mature and highly competitive industry, which primarily reflects the nature of the supermarket industry. In Australia, this industry operates as an oligopoly with significant barriers to entry, mostly based on brand name and an extensive store network. The low return on capital is exacerbated by the significant goodwill and intangible assets recognised on the acquisition of Coles in 2007.

However, it is not all bad news for investors. Coles has a cash conversion ratio of greater than 100%, which is unusual. The cash conversion ratio measures the profits that are being turned into actual cash receipts. Most companies will have a ratio of less than 100%, as companies buy raw materials to convert into finished goods that are subsequently sold. Alternatively, the company will have a percentage of their customers that might be late paying their accounts.

Coles achieves a cash conversion ratio of greater than 100% because suppliers such as Kellogg’s deliver a box of Just Right Cereal to Coles and are paid at a later date, generally between 60 and 120 days. When Coles sells that box of sugary cereal to me for cash within two weeks of delivery, Coles has received cash for selling the box of cereal before they have actually paid for it. Here Kellogg’s have effectively funded Coles’ working capital. This is obviously a positive for shareholders and supports a high dividend payout ratio.

Why is the vendor selling?

The seller’s motivation is one aspect we look at closely when analysing a new company. Historically investors tend to do well where the new company or IPO is a spin-off from a large company exiting a line of business or the vendors are using the proceeds to expand their business. Here Wesfarmers are demerging Coles and are giving their existing shareholders a share in Coles for every share of Wesfarmers they own, and Wesfarmers intend to retain a 15% share in the Coles business. Under these conditions, Wesfarmers have a strong incentive for Coles to be successful and to provide it with the best start to its life as a new company. Conversely, where the new company is an IPO conducted by private equity owners that are not retaining any ownership, the sellers are incentivised to maximise their exit price rather than the long-term health of the business.

Coles operates in the highly competitive domestic food and liquor business and going forward their growth will essentially track Australian GDP growth. Currently, Coles holds a 33% market share of Australian supermarket spend and 16% of retail alcohol sales. Realistically it would be very hard for Coles to increase their market share meaningfully in either of these categories, without provoking an immediate reaction from competitors Woolworths and Aldi. Fundamentally Coles is a stable, low growth mature business.

Investors more cynical than us might look at remuneration conditions for senior management in the Wesfarmers Annual Report and notice that a large portion of the CEO’s bonus is tied to delivering a high RoC (return on capital). Notably, removing Coles could make it easier to hit those targets. For example, in the last six months, Coles delivered a RoC of 9%, whereas Bunnings Australia (which is remaining with Wesfarmers) had a RoC of 47%! In the last 12 months, Wesfarmers management has made some pretty significant changes to their business, exiting the UK hardware market, divesting their coal assets and now spinning off Coles.

Is the business profitable?

Yes, over the 2018 financial year Coles had revenues of $39 billion that resulted in a profit of around $1.4 billion. Coles operates in a constrained environment with 30% market share in each of the Australian grocery and liquor markets, which are dominated by large, well-resourced competitors selling the same or similar products sourced from a small pool of manufacturers. Any aggressive moves to grow market share via reducing price would be met quite swiftly by Woolworths and Aldi. Outside of growth in the Australian grocery spend, the main avenue for Coles to increase profits is via cutting costs. Strategies might include improving distribution efficiencies or boosting the number of home brand items on their shelves (while cheaper for consumers these have a higher profit margin for Coles and Woolworths).

However, Coles’ recent 8-week Little Shop campaign of tiny collectable toys based on branded in-store goods (small plastic jars of Vegemite) has been estimated to have generated an additional $200m in sales in the first 2 months of FY2019. This was not a big surprise as the father of an 8-year-old girl who was aggressively pestering adults that she knew to shop at Coles during this period.

Returns to Shareholders

Coles are expecting to pay out between 80-90% of earnings in dividends, which will result in Coles being a high yield, low growth company. Interestingly, whilst Wesfarmers had an excess franking account balance of $978 million as of June 2018, this will remain with Wesfarmers so at birth Coles will start with a no franking credits. This is not particularly unusual, for example when BHP spun off S32 in 2015, BHP’s franking credits remained with the parent. This approach is often connected with demerger tax relief from the ATO. Tax relief means that Wesfarmers shareholders defer any tax payable until they sell their Coles shares. Given this large franking account balance, we would not be surprised to see Wesfarmers announce a capital return in 2019 in an effort to return this to shareholders.

Financial stability

Coles will be listed with gearing of around 35%. From the demerger documents, Coles will be taking with it a high proportion of Wesfarmers’ debt ($2 billion) relative to the EBIT that it generates, though this is a business with stable cash flows that can handle debt. When we raised this item with management, we were told that the higher percentage of group debt that Coles are assuming reflects the large percentage of capital Wesfarmers have put into Coles over the past decade, which we consider a fair response.

How attractive is the price?

With a price not being set, it is tough to make a judgement as to valuation, other than that the dividend yield is likely to be attractive. We expect Coles will have an enterprise value between $16 billion and $19 billion – making it a top 30 company – and it will trade at a multiple of about 10- or 11-times EBIT and a PE ~ 16x (a 10-20% discount to Woolworths). Back solving for these numbers, Atlas expects that Coles will have a share price between $14 and $15.50.

Risks

Coles faces the potential for store sales to migrate online in the future, fuelled by Amazon – although food and liquor is not an area in which Amazon is focusing in Australia. Coles and Woolworths have both been pre-emptively investing in their online offering to protect their existing business. We note that in much more densely populated Germany, Amazon offers fresh food delivery in only 10 major cities. Conceptually, fresh groceries are less desirable for Amazon in Australia, as many items such a meat, milk and fruit need to be refrigerated. This would necessitate Amazon building separate refrigerated distribution centres in addition to the centres housing books and headphones.

As part of the separation, Coles announced that they would be consolidating five existing distribution centres into two automated sites (one in Sydney and one in Brisbane). This is expected to cost ~$700 million over the next 5 years and will help lower Coles’ operating costs. Automation and consolidation of distribution are designed to allow Coles to compete with Woolworths, Aldi and Amazon.

Our take

Generally, it is hard to forecast how a new company will perform post IPO, as often the market is not that familiar with the new company and its register might be populated by short-term shareholders such as hedge funds that are seeking to make short-term gains. Sometimes (such as in case of the recent spin-off of OneMarket by Westfield) shareholders – including Atlas – aggressively sold their holdings of the spun-off company, because a tech company with no dividend and significant capital requirements was quite different from the parent, a distribution-paying property trust. In the case of Coles, we don’t see this to be an issue, as one of the main reasons for owning Wesfarmers was to gain access to Coles.

We own Wesfarmers in the Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio and will be receiving Coles shares next week. Coles passes our internal quality filter model and we see that exposure to food and liquor offers investors a defensive earnings stream with sustainable comparative advantages in their key markets. We also see that in the medium term, the new Coles could lead to more rational competition in the Australian grocery market and healthier returns for the major participants.

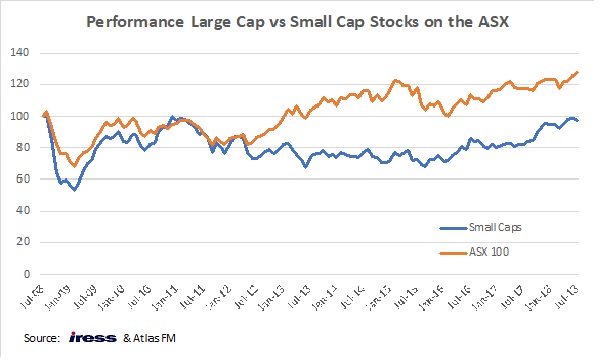

Additionally, after a recovery in 2009, the above chart shows that the small capitalisation index was unchanged until early 2017. Over this same period the large caps did well, particularly in the period 2012 -2015. This occurred as the large cap financials benefited from the removal of competition and falling rates globally, whilst the mining stocks bounced back courtesy of higher commodity prices from a range of Chinese stimulus plans.

Additionally, after a recovery in 2009, the above chart shows that the small capitalisation index was unchanged until early 2017. Over this same period the large caps did well, particularly in the period 2012 -2015. This occurred as the large cap financials benefited from the removal of competition and falling rates globally, whilst the mining stocks bounced back courtesy of higher commodity prices from a range of Chinese stimulus plans.