Earlier this month Atlas sent out the tax statements for the Atlas High Income Property Fund, and for a relatively straightforward fund with a simple tax structure (income is passed through to investors untaxed), I was surprised at the number of potential categories of income.

As this sparked a few questions in this week’s piece we are going to look at two relatively unique aspects of taxation in Australia and how some companies and in particular listed property trusts, can structure themselves to limit taxes paid.

Franking Credits

Franking credits (or dividend imputation credits) allow an investor to get a taxation credit at a personal level against the tax already paid at a corporate level on a dividend. Prior to the introduction of franking credits in 1987, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) would tax both the company and then the investor on the same income, effectively doubling the tax paid on the same source of profit. The franking credit regime was further sweetened in 2000, when changes were made that allowed investors on tax rates below the corporate tax rate of 30% to claim surplus credits as a refund. Prior to 2000 the ATO retained surplus franking credits.

The percentage of a distribution that is franked depends on the amount of tax paid by the company in Australia. For companies that earn all of their profits in Australia (such as Westpac for example) will be able to frank their dividends at 100%, whereas pathology company Sonic Healthcare can only provide frank their dividend at 20%. This is because most of Sonic Healthcare’s earnings are sourced from outside Australia. Some companies such as BHP build up large franking credit balances where they pay tax on the profits earned in Australia, but retain profits to fund capital expenditure to build and maintain mines, only returning a smaller amount to shareholders as dividends. This franking account balance further accumulates when a company like BHP is also listed on a foreign exchange with investors that receive dividends without Australian franking credits.

Franking (or dividend imputation credits) are not a feature of global markets outside Australia and New Zealand, with only Canada, the UK and Korea retaining a partial imputation system. This system encourages Australian companies to pay high dividends, whereas the tax system in the US encourages small dividends and share buy-backs as a means of returning profits to shareholders.

Why listed property trusts don’t pay franking credits

Listed property trusts such as GPT do not generate meaningful amounts of franking credits because they are structured to minimise the amount of tax they pay. Listed property trusts are a different corporate structure Act to industrial companies such as BHP under the Corporations and as a result they face different taxation treatment.

A company such as BHP is a separate legal entity that can hold assets in its own name. As a result, its shareholders do not own the company’s assets. The company’s board of directors can decide what dividend to declare (if any) on the company’s after-tax profits, after they have decided how much earnings to retain to fund expansion.

Alternatively, a trust such as GPT is a different legal entity where the trustee, holds the ‘legal’ title to their underlying shopping centre and office assets on ‘trust’ for the underlying investors, who hold the ‘beneficial’ title to those same assets. Unitholders in GPT are thus the beneficial owners of the assets held and are entitled to the income derived from the use of those assets.

Consequently, a trust itself does not pay income tax on profits (rents less outgoings and interest costs), provided that over 90% of the profits of the trust have been fully distributed to the beneficiaries in the relevant financial year. The benefit of a trust structure is that it allows for the distribution of income to investors in a tax efficient manner, as unlike BHP (with its $13 billion-dollar franking credit account balance), a trust is a ‘transparent’ vehicle for Australian tax purposes as no tax is paid (in normal circumstances) by the trust Itself.

More Australian tax gymnastics: Stapled Securities

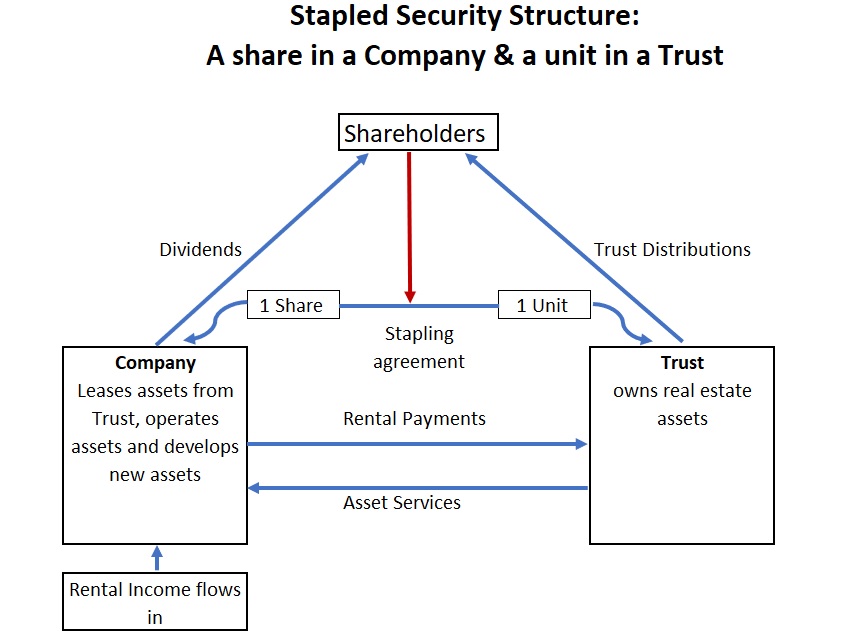

Continuing on with the theme of listed companies managing their tax, many listed property trusts are also “Stapled Securities”. Stapled Securities involve the binding or “stapling” together of two separate securities such as a share in a company and a unit in a trust which cannot be traded separately. This type of structure is used quite intensively in Australia by property trusts and infrastructure funds to shield their untaxed passive property income from the taxable profits earned by a management company. Similar to franking credits this is a tax feature that is popular in Australia, but less so globally. Canada stopped the use in 2011 and the US in 1984. The rationale used by governments in North America for stopping stapled structures was to boost the tax take from corporations.

These corporate gymnastics is done for reasons of tax arbitrage. If stapling reduces the total tax bill paid on income generated by a particular business activity, shareholders benefit. Based on the time value of money rational investors would prefer a pre-tax stream of income and then pay tax at a later date on their personal tax rate, to payments that have already been taxed by the government from which the investor has to then apply for a refund.

In the above table if you own a unit of a GPT Group this is a stapled security comprises two separate assets for capital gains tax purposes; a General Property Trust unit and a GPT Management Holdings Limited share. These GPT securities are ‘stapled’ together and cannot be traded separately. The trust holds the portfolio of GPT office tower and shopping centre assets, while the related GPT Management Holdings company leases and operates these assets and manages any development opportunities.

In the case of GPT, because the General Property Trust is a “pass-through” trust for tax purposes, the income it receives is not subject to company tax, so long as paid out to unit holders. Stapled securities often make the rental payments by the Company for the use if the Trust’s assets high to minimise the Company’s taxable income (i.e. profits from funds management and developments). If GPT’s management and passive rent collecting entities were merged, GPT’s rental income stream would be taxed at 30%. However, in 2016 GPT paid a mere $14 million in tax on a pre-tax profit of $551 million.

Our Take

Australian investors face a more complex tax environment than is present elsewhere in the developed world. Whilst as the fund manager it would be nice to provide franking credits on the quarterly distributions paid by the Atlas High Income Property Fund, it is certainly simpler to be able to stream the pre-tax income from both property trust distributions and call options sold to the underlying investors without taking out any tax. Additionally, investors get the use of this pre-tax cash today, rather having to wait until after they have submitted their tax returns to get a cheque from the government.