April 2020, many experts predicted that residential real estate was set for a significant correction over the coming year based on expectations of a deep recession and sharp increases in the unemployment rate. Westpac’s economists forecasted an 8% fall in GDP in the coming year, unemployment to reach 10%, and a 20% fall in house prices and, based on this, took a $2 billion provision for expected loan losses.

Instead of falling, house prices accelerated over the past year with the latest CoreLogic RP Data Daily Home Value Index for March 2021 showing a +5.7% increase in national house prices led by Sydney and Brisbane.

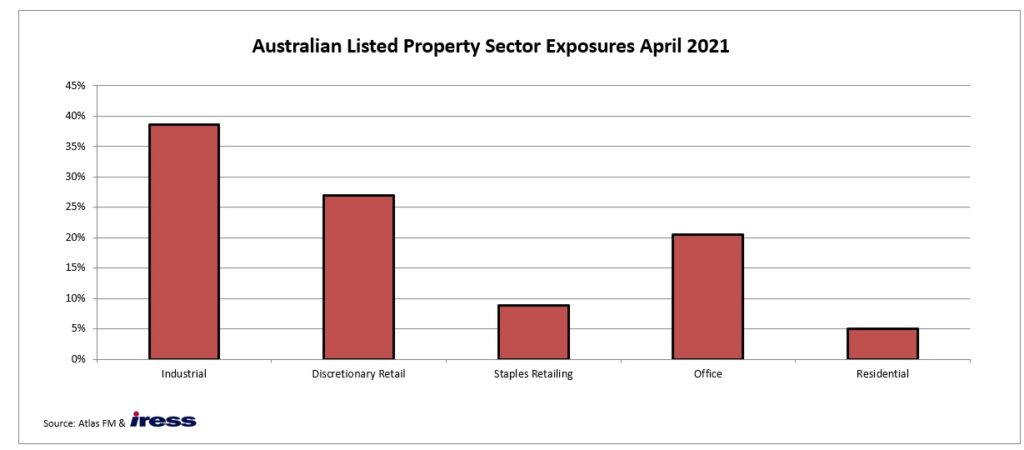

As the manager of a listed property fund, Atlas has recently received questions about gaining exposure to rising residential real estate prices without buying a house or apartment. However, as residential real estate is only a tiny portion of the overall listed property index on the ASX, this is an asset class that institutional investors largely ignore. In this week’s piece, we look at why listed property trusts avoid buying houses and apartments.

Listed real estate is not houses

Unlike the US or UK, where residential is a significant component of the listed property index (US residential REIT exposure 18%), the Australian index’s residential real estate exposure is relatively small at only 5% (see below table).

Further, the residual real estate exposure on the ASX consists of the development arms of diversified property trusts such as Stockland (mainly house and land packages) and Mirvac (predominantly apartments). Moreover, neither of these two trusts intends to hold residential property on their balance sheets over the medium term. Greater returns are available from developing and selling residential real estate rather than collecting rents. However, Mirvac has one build-to-rent project located in Sydney’s Olympic Park, assisted by some tax concessions, namely a 50% discount on land tax for the next 20 years.

Residential property has attracted little interest from institutional investors as retail investors have an investment edge. In the below chart, residential real estate comprised 5% of the S&P/ASX 200 A-REIT index in April 2021 or $6 billion. This is dwarfed by the value of the currently ‘beaten-up’ discretionary retail ($34 billion), industrial ($49 billion), and office ($26 billion) real estate assets listed on the ASX.

In our view, there are three structural reasons why retail investors rather than institutional investors are the primary buyers of residential real estate in Australia.

Capital gains tax breaks for homeowners ‘crowds out’ corporates

Firstly, in Australia, the tax-free status of capital gains for owner-occupiers selling their primary dwelling bids up the purchase prices of residential real estate. For example, when a company generates a $500,000 capital gain from selling an apartment, they would approximately be liable to pay $108,000 in capital gains tax. In contrast, the owner-occupier pays no tax on the capital gains made on a similar investment.

This discrepancy in the tax treatment allows the owner-occupier to pay more for the same home, anticipating tax-free capital gains not available to institutional investors such as property trusts.

Negative gearing

Similarly, individual retail investors benefit from the generous tax treatment in Australia that allows them to negatively gear properties. There are three types of gearing depending on the income earned from an investment property: positive, neutral and negative. A positively geared asset generates income above maintenance and interest costs, and obviously, neutral gearing generates no income after expenses and interest.

A property is negatively geared when the rental return is less than the interest repayments and outgoings, placing the investor in a position of losing income annually, generally an unattractive position. However, under Australian tax law, individual investors can offset the cost of owning the property (including the interest paid on a loan) against other assessable income. This incentivises individual high-taxpaying investors to buy a property at a price where cash flow is negative to maximise their near-term after-tax income and bet on capital gains.

Whilst companies and property trusts can also access taxation benefits from borrowing to buy real estate assets, a wealthy doctor on a top marginal tax rate of 47% has a stronger incentive to raise their paddle at an auction.

Yields on residential property too low

At current prices, the yield that residential property is not attractive for listed vehicles. At the moment, the ASX 200 A-REIT index offers an average yield of 4%. This compares favourably with the yields from investing in residential property. SQM Research reported that the implied gross rental yield for a 3-bedroom house in Sydney is only 2.7%, with a 2-bedroom apartment yielding slightly higher at 3.4% in April 2021. After borrowing costs, council rates, insurance, and maintenance capex, the net yield is estimated to average around 1%. This low yield on residential real estate contrasts sharply with the average yield after costs on commercial real estate currently above 4.5%. As listed property trusts traditionally attract investors that are focused on yield and many property trust CEO’s are remunerated based on growing distributions per unit; there is a strong incentive for Listed Property trusts to buy higher yielding commercial property and avoid lower yielding residential assets.

This piece originally appeared in Firstlinks “Why you can’t invest in residential property in the listed market”

Our Take

While housing comprises the most significant component of the overall stock of Australian real estate assets and talking about house prices is the one sport that unites all Australians, residential real estate holds little interest for institutional investors, especially for income-focused investors such as Atlas Funds Management.

Speculating on houses and apartments is one of the few areas of investment where retail investors have an advantage over well-resourced institutional investors.In the future institutional investors could play a greater role in owning residential real estate as they do in the UK and the USA. However, this would require either the extension of further tax concessions to corporates or alternatively removing these concessions such as negative gearing from households, two politically very unpalatable courses of action.