Banks, miners could make dividends rain in 2021

While Australian dividends fell 0.2 per cent year-on-year during the first quarter, the rest of the globe dropped 1.7 per cent from the year-earlier period. The outperformance was driven in part by the high concentration of Australia’s market in the banks and miners.

Blog

Banking Profits Roaring Back

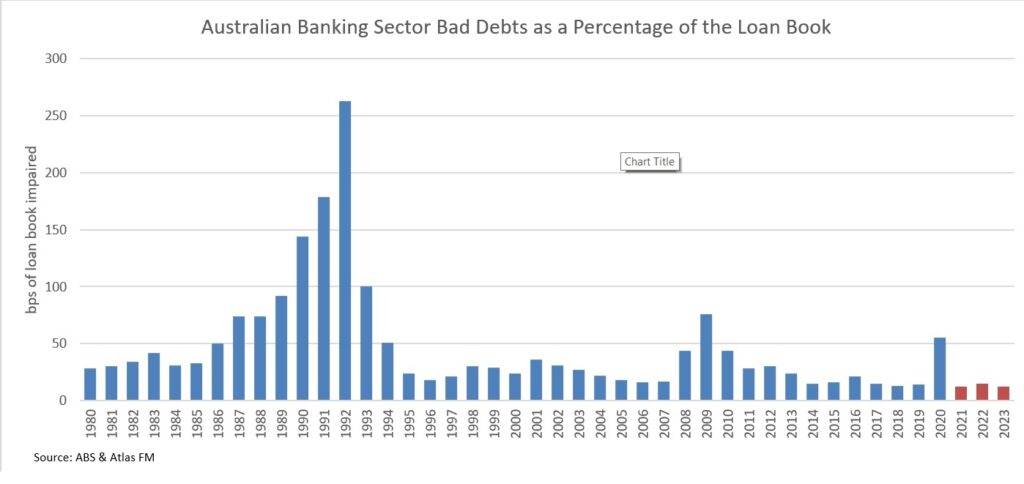

Twelve months ago, the consensus view was that 2021 would be dreadful for Australia’s banks. The year was expected to be more challenging than the GFC and, similar to 1992, when both Westpac and ANZ came close to insolvency crippled by bad loans to entrepreneurs such as Alan Bond, Chris Skase and Robert Holmes à Court. Indeed 2021 was predicted to deliver high unemployment, more capital raisings, minimal dividends and rising loan losses eating hungrily into carefully built capital buffers. The May 2021 reporting season proved these forecasts incorrect, with bank dividends increasing sharply, loan loss provisions from last year written back, and management talking about share buybacks later on in the year!

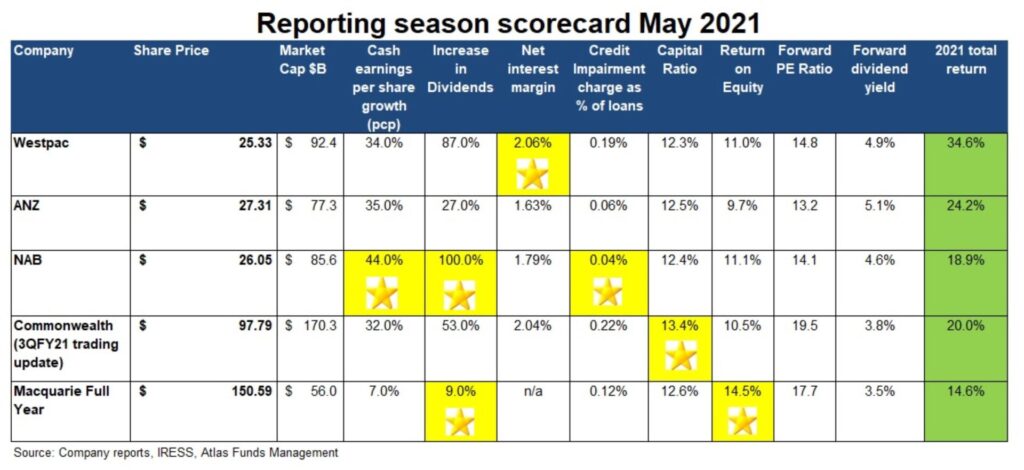

In this piece, we will look at the themes in the approximately 850 pages of financial results released over the past two weeks, including Commonwealth Banks 3rd Quarter 2021 Update, awarding gold stars based on performance over the past six months.

What Pandemic?

The key feature of the May results for the banking sector was a dramatic recovery in the financial health of corporate and household Australia. Twelve months ago, the base case for the banks was unemployment between 10-12% and house prices falling by between 15-20% throughout 2020, with further deterioration expected in 2021. This cautious stance saw Westpac taking $1.8 billion and ANZ $1 billion in provisions due to expected losses from Covid-19 and most banks declining to pay a dividend. The lack of dividends surprised many investors as Westpac paid a dividend even during its near-death experience in 1992.

Instead of seeing a steep increase in unemployment and falling house prices, which would have increased bad debts for the banks, Australia was one of the first nations to regain all jobs lost through the pandemic, reporting an unemployment rate 5.6% in March.

This optimism was mirrored in the banks’ recent results presentations, which showed the number of stressed customers falling steadily throughout the year. Indeed, from looking at the recent set of bank results, it is often tough to discern any impact of Covid-19. For example, ANZ reported bad debt charges of 0.08% of their loan book, an all-time low and of the 121,000 home loans in deferral last May, only 2,000 have moved to hardship, with the rest returning to making payments.

The below chart shows bank bad debts over the past 40 years. In 2021 the combination of increases in employment, sharply rising house prices and record low interest rates have seen bad debts fall significantly. The recovery from Covid-19 has proved to be faster than the GFC, and nothing like the decade it took the banks to recover from the 1991/92 recession.

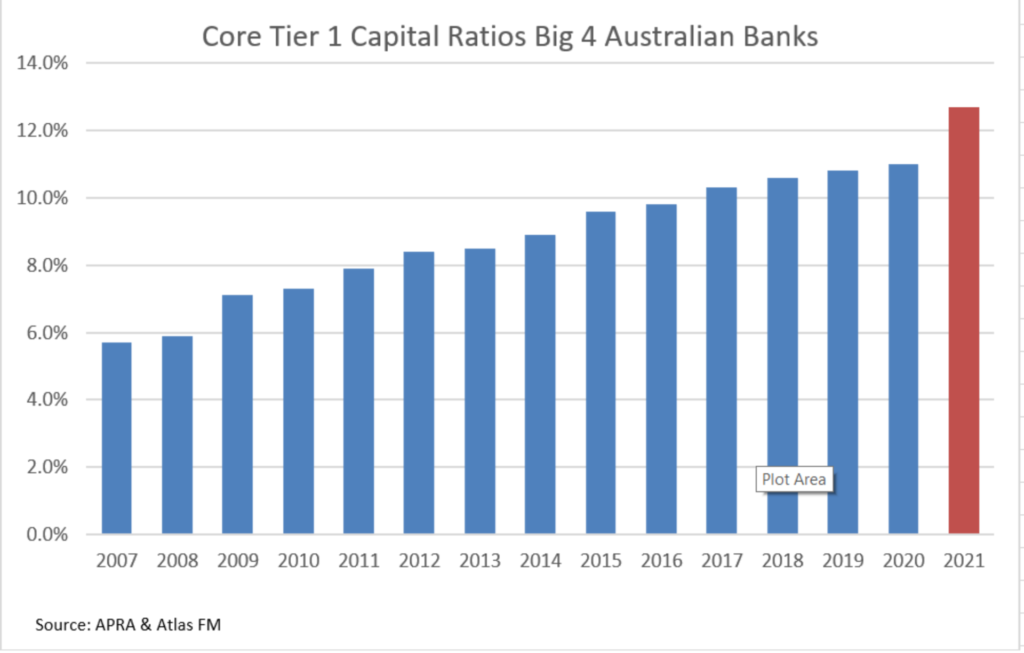

Too Much Capital

All banks have a core Tier 1 capital ratios well above the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s (APRA) ‘unquestionably strong’ benchmark of 10.5%, aided by asset sales in wealth management and low dividend payout ratios in 2020. Australia’s banks entered 2020 with a greater ability to withstand an external shock than was present in 2006 going into the GFC. From the below table, you can see that the banks have been building capital, particularly since 2015 when APRA required that the banks have “unquestionably strong and have capital ratios in the top quartile of internationally active banks”. Furthermore, in response to the 2018 Financial Services Royal Commission, the banks further increased capital by divesting their wealth management and insurance businesses. This resulted in the banking sector remaining well capitalised, with the capital only building as the expected loan losses from Covid-19 have not eventuated.

n the March management presentations, there was again a tone of self-congratulation from bank executives at their prudence for having such high levels of capital. While during the GFC, all banks needed to raise capital, in 2020 NAB was the only bank to issue new equity raising $3.5 billion in April 2020. Commonwealth Bank came out ahead in May with the strongest capital ratio at 13.4% among the banks. We expect that towards the end of 2021, most banks will seek APRA approval to return capital to shareholders, either special dividends or share buybacks. Management teams are generally incentivised to conduct share buybacks which permanently reduce outstanding equity, thus making management return on equity (ROE) targets that trigger bonuses easier to achieve.

Gold Star

Don’t Waste a Crisis

Winston Churchill famously said, “never let a good crisis go to waste,” and several bank management teams appear to be taking his advice, looking to take advantage of social distancing brought on by Covid-19 to rationalise their sprawling branch networks. On average, the major banks each have over 1,000 branches around Australia. The banks have experienced a decline in usage of these branches over the past decade, as most bank transactions are now conducted either online or via smartphones. Last month NAB reporting that 93% of retail transactions are now conducted electronically.

Rationalising bank branch networks, while politically unpopular, represents an opportunity for the banks to reduce their cost base and obtain a divided from their extensive investment in technology. In May, Westpac announced plans to reduce their annual cost base by $2 billion to $8 billion via a combination of cutting head-office jobs and closing branches. In Martin Place one of the major banks has a branch that we walk past regularly, which despite being fully staffed with three tellers, branch managers and an information counter is invariably bereft of customers, even at peak times. We estimate that the cost to operate this lonely branch occupying prime real estate would be several million dollars per annum.![]()

Gold Star

Rising Net Interest Margins?

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the biggest issue that the banks were expected to face over the next few years was maintaining net interest margins as the cash rate moved towards zero. Banks earn a net interest margin [(Interest Received – Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] by lending out funds at a higher rate than borrowing these funds either from depositors or on the wholesale money markets.

When prevailing interest rates are cash rate is 6%, it is much easier for a bank to maintain a profit margin of 2% than when the cash rate is 0.1%. Falling interest rates reduce the benefit that banks get from the billions of dollars held in zero or near-zero interest transaction accounts that can be lent out profitably. However, this cheap source of funding continues to benefit the banks. In their result, Westpac revealed that as of March 2021, the bank held $257 billion on accounts earning less than 0.25%, an increase of $61 billion over the last six months that indicates that a portion of the stimulus payments are still being saved and not spent.

The March 2021 reporting season saw net interest margins increase for the central banks due to lower funding costs. The banks more heavily exposed to mortgages (CBA and Westpac) traditionally have higher margins than the business banks (NAB and ANZ) which face competition from international banks when lending to large corporates. Westpac posted the strongest net interest margin in May with an increase of 0.05% to 2.09%. While this sounds like a minute increase, it becomes significant when played out over a loan book of $690 billion!![]()

Gold Star

Dividends

In the lead up to the May 2021 reporting season, it was challenging to forecast bank dividends. Forecasting involved assessing how bank management teams were weighing up the need to be conservative if economic conditions deteriorated with the desire to reward shareholders who saw their dividends cut heavily in 2020. In May, all of the banks increased their dividends significantly over what was paid on the last half in response to higher profits, low loan losses and the removal of restrictions placed by APRA in 2020 that limited dividends to 50% of earnings. NAB increased their semi-annual dividend by 100% to 60 cents, though this is still 30% below pre-Covid 19 levels. Macquarie wins the gold star, increasing their dividend by 9% and was the only bank not to cut dividends as the global bank generated record profits during a pandemic affected year.

Gold Star

The road back to Pre-COVID-19 levels of Profits and Dividends

While the banks will eventually see profits from banking return to pre-COVID-19 levels, the road back to the same dividends per share in 2019 will be slow due to a combination of asset sales (lost earnings) and equity issues (increased shares) from NAB and Westpac. However, Atlas believes that the path to restoring profits to pre Covid-19 levels is likely to be quicker than both the GFC and the 1990s recession. In 2021 the banks have a higher credit quality in their loan books and fewer lingering issues to deal with; no Quintex, Bond Group, ABC Learning, US CDOs or UK retail banking exposure. Additionally, customers feeling financial stress now face interest rates in the low single digits, not the 18-20% mortgage rates seen in the early 1990s or 7-9% during the GFC.

We expect dividends to continue to increase across the banking sector in 2021, provided the economy remains robust, and there are no further significant outbreaks that shut down sections of the economy. Given the high levels of capital, one lever that bank management teams have to drive earnings and dividends per share growth is to conduct significant share buybacks to reduce their share count.

This piece originally appeared in Firstlinks

Our Take

Twelve months ago, Atlas took an optimistic stance towards the banks, viewing that due to the more conservative positioning of their loan books, the bad debt trajectory for the banks would be closer to 2009-11 rather than the early 1990s. This stance has proved to be quite pessimistic, and we have been surprised at how well the banks have managed the Covid-19 crisis, which played out very differently from the GFC.

Unlike during the GFC, there have been no major corporate collapses, and massive stimulus measures put in place by the Federal Government have indirectly benefited Australia’s banks. These stimulus measures maintained employment during periods of high uncertainty, boosted retail sales, and helped fuel rising house prices; all of which have contributed to the banks reporting loan losses in 2021 that were a fraction of expectations made 12 months ago. While the outlook for the banks remains far from certain, Australia’s banks have historically performed well coming out of crises that have reduced foreign competition and allowed them to solidify the banking sector oligopoly.

JB Hi-Fi – Running through the company in detail

In all of these cases the nay-sayers have been proved wrong with JBH returning +150% over the past 5 years (vs ASX 200 +35%) and the stock being a graveyard for short-sellers Earlier this week JBH was again in the news releasing a very solid trading update for Q1 2021 (Q1 2021 sales up 11.5%), but also announcing that their CEO had jumped ship to clothing retailer Premier Investments.

Hugh Dive from Atlas Funds Management walks us through the finances and quality metrics of JB Hi Fi to understand how they’re a world leader in the cost of doing business, despite the relatively high Australian wages on the global scale.

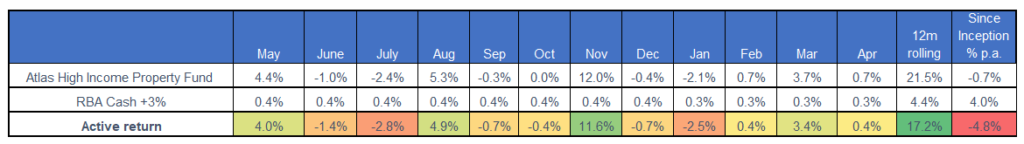

April Monthly Property Income Fund Newsletter

The Atlas High Income Property Fund had a steady month gaining +0.7% with share prices continuing to recover from the dark days of early 2020 where the market was questioning the value of most classes of real estate. Over the month, several Trusts in the Fund provided positive trading updates, showing that rent collections from tenants are now back to pre-pandemic levels. Twelve months ago, commercial landlords faced government legislation preventing the eviction of tenants not paying rent if deemed to be impacted by Covid-19.

Concerns about inflation in the medium term was a key theme over April. The Portfolio is hedged well against rising inflation with rents and toll revenues inflation-linked. Indeed, as a legacy of the GFC where many companies struggled to refinance debt, most Trusts in the Portfolio now have long term fixed-rate debt. Rising inflation is likely to see higher profits as revenues grow faster than interest payments

Go to Monthly Newsletters for a more detailed discussion of the listed property market and the fund’s strategy going into 2021.

AFR:As property stocks soar, valuation becomes a tricky art

An incredible turnaround

Hugh Dive, chief investment officer of Atlas Funds Management, says Australian bank stocks are the best way to play the housing boom. “Rising house prices will enable banks to write back more of their bad-debt provisions this financial year and next. That will drive bank earnings and dividends higher.”

Dive was bullish on bank stocks after they crashed in March 2020, believing expected loan losses would be more moderate than the market thought.

His preference remains Westpac, followed by ANZ, which also reported this week, and the Commonwealth Bank. “Share-price gains might be slower from here, but the outlook for the Australian banking sector is the best in years. We believe bank stocks will outperform.”

The turnaround in bank stocks is incredible. A year ago, the banks forecast savage falls in house prices and investors braced for surging bad debts and bank dividend cuts. Today the banks predict double-digit house-price growth, bank dividends are up and there is speculation of share buybacks in the sector later this year.

Dive also favours JB Hi-Fi, a retailer at the epicentre of the property and work-from-home booms.

After soaring last year, JB Hi-Fi shares have eased in recent months. CEO Richard Murray’s surprise resignation and buyer fatigue in retail stocks have weighed on JB Hi-Fi, even though it noted strong sales growth over the past nine months in its latest trading update.

“JB Hi-Fi’s Good Guys division is performing strongly due to higher demand for white goods,” Dive says. “The market previously had concerns about the Good Guys acquisition and is still underestimating that operation. JB Hi-Fi will continue to benefit from housing strength over the next few years.”