- January proved to be a very volatile month dominated by macroeconomic news such as a short squeeze in a troubled US small capitalisation company GameStop, rather than company fundamentals as companies were in blackout before the February reporting season. Most global markets finished in negative territory after a sell-off in the last week of January.

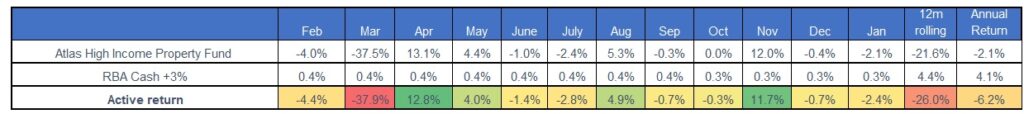

- The Atlas High Income Property Fund declined by -2.1% in January on general market sentiment rather than investment fundamentals. Atlas is looking forward to the February profit season which we expect will show both a continued improvement in the financials of the Trusts that we own and that management will guide to higher distributions through the rest of 2021.

- Twelve months ago bank 180-day term deposit rates were at 1.25% a return that seemed quite shockingly low at the time, but now looks relatively healthy. Throughout the past year, term deposit rates have fallen further to be between 0.2% and 0.4%, significantly below the inflation rate of 1.5%. 2020 was challenging for property investors as share prices fell based on the false assumptions that rents won’t be collected and that vacancies would skyrocket as large numbers of corporations slid into bankruptcy. In 2021 we see that rent-collecting trusts offering stable distributions significantly above the cash rate will be re-rated higher by investors.

Go to Monthly Newsletters for a more detailed discussion of the listed property market and the fund’s strategy going into 2021.