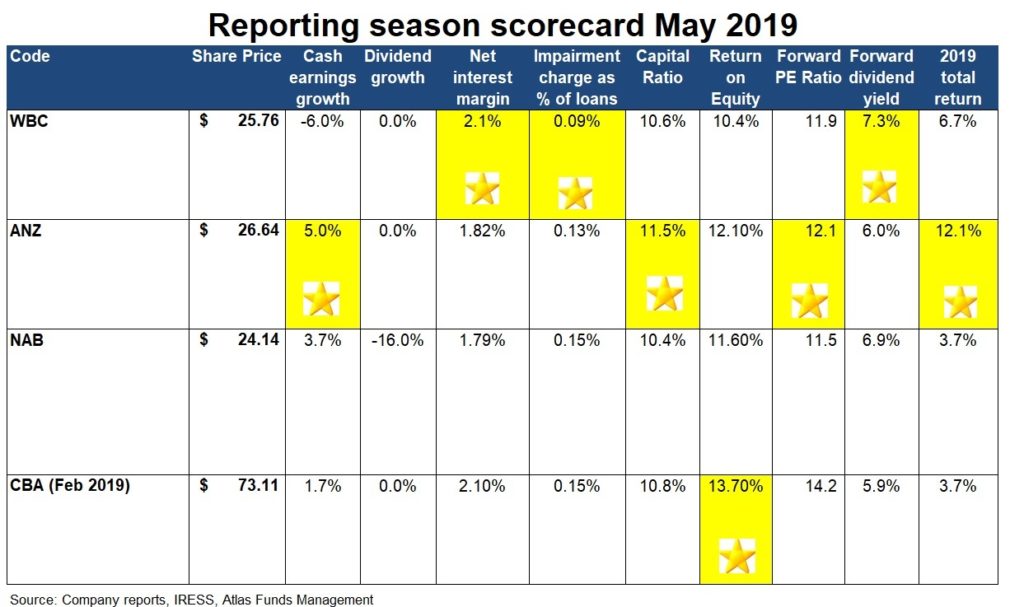

On Monday Commonwealth Bank released their quarterly results. This concluded the May banks reporting season in which NAB, ANZ and Westpac revealed their profits for the six months ending March 2019. The revelations of the Royal Commission on Financial Services have resulted in extensive remediation provisions, increased compliance costs and a spike in legal fees, at a time where credit growth has slowed dramatically. This unusual set of circumstances has generated a complicated set of financial results to analyse; a task made harder still by Commonwealth, ANZ and Westpac all divesting divisions.

In this week’s piece, we are going to look at the themes that can be gleaned from the approximately 800 pages of financial results released over the past 14 days by the financial institutions that grease the wheels of the Australian capitalism and award gold stars based on performance over the past six months.

Remediation

Customer remediation was a key theme for the results in 2019, with banks

compensating customers or taking provisions related to financial advice,

banking, insurance and consumer credit. Australia’s banks have taken

remediation provisions over the past 12 months of between $900M (ANZ) and $1.4b

(Westpac), with NAB and Commonwealth around the $1.1b mark. ANZ’s lower level

of provisioning does not reflect any lack of prudence, but rather its

historically low level of exposure to financial advice and funds

management.

No

star is given. The fact that the banks have made these provisions is bad for

both customers and shareholders.

Profit growth?

Across the banking

Gold Star

Dividends

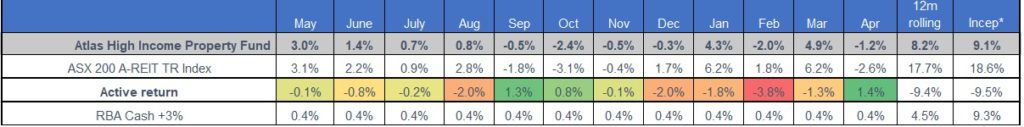

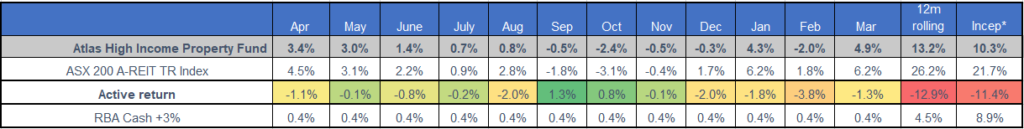

Unsurprisingly given the level of remediation provisions and political scrutiny, no bank grew their dividend per share in 2019, though NAB did cut theirs by 16 cents to $0.83. This cut did not spark much of a reaction from the market as NAB had been paying out close to 100% of cash earnings after remediation charges in 2018. This was unsustainable as a bank needs to retain some earnings to grow their capital base and thus, their ability to lend to customers. Westpac maintained their dividend, but introduced a 1.5% discount on their dividend reinvestment plan, a move designed to raise capital. Interestingly, Westpac also brought forward its interim dividend payment date by nine days to June 24 2019. This move gives Westpac’s investors three dividends in the 2019 financial year, with payments in July 2018 and December 2018 as well as this one in June 2019. Atlas interpret this as a move to designed to beat Labor’s changes to franking credits.

Gold Star

Bad

debts

One of the biggest drivers of earnings growth over the last few years has been the ongoing decline in bad debts. Falling bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay and that the outstanding loan amount is greater than the collateral eventually recovered. Bad debts remained low in 2019, with the housing banks Westpac and Commonwealth reporting the lowest level of bad debts despite a cooling in the East Coast property market.

Furthermore, at the big end of town, there were no major corporate collapses over the past six months, keeping corporate bad debts low. ANZ, NAB and Commonwealth reported a marginal increase in bad debts, albeit at levels that are around half of the long-term average (excluding 1991) of 0.3% of gross loans and acceptances. Westpac reported unusually low bad debts at a mere 0.09% of loans, though this low bad debt charge was boosted by a release of provisions previously taken on loans made by their business bank.

Gold Star

Keeping it simple

The main new theme to emerge from this reporting season was that banks are

looking to reduce their footprint on the Australian financial services

landscape by divesting businesses that are deemed to be non-core or are in

areas that have the potential to damage the reputation of the bank’s core

lending business. Over the last year, Commonwealth Bank has sold their

insurance and funds management business, ANZ Bank has sold their wealth

business to IOOF – though this may come back due to ongoing issues at IOOF –

and in March Westpac announced that they are exiting personal financial advice.

NAB also announced plans to sell MLC wealth management by 2019.

These moves can be seen as acknowledging that the costly exercise of creating

vertically integrated financial supermarkets was a mistake. While some of the

moves to sell these carefully constructed divisions may be attributed to the

events of the Royal Commission, some of the sales were consummated well before

the titans of Australian finance faced the harsh light of the witness stand.

No Star Given –

ultimately a flawed strategy

Interest Margins

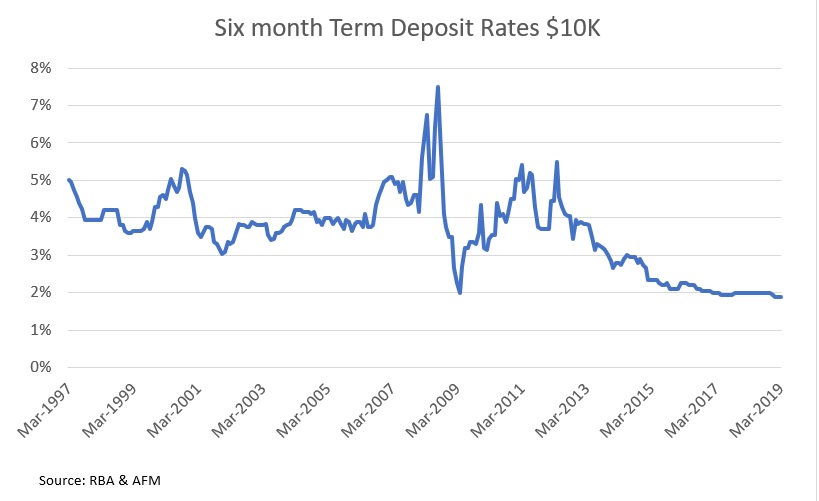

The banks’ net interest margins [(Interest Received – Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] in aggregate decreased slightly in 2019. The decrease was attributed to increased competition and customer remediation charges. However, these pressures were offset by pricing mortgages upwards and, as many retirees will be aware, reducing the interest rate being paid on deposits. Looking forward, the bank’s interest margins are likely to be fairly healthy as their funding costs have continued to decline over 2019. Funding cost refers to the overall interest rate paid by the banks to source the funds that are used for short-term and long-term loans to their borrowers. Westpac reported the highest net interest rate margin in May 2019, which reflects both their greater focus on mortgages (which attract a higher margin than business loans) and the impact of higher pricing on those loans.

Gold Star

New

Zealand

Late in 2018, the RBNZ released a consultation paper on bank capital requirements, essentially saying that they would like the banks that lend to New Zealanders maintain a Tier 1 Capital level of 16%, with a decision to be made in September 2019. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA)’s standard is 10.5%. New Zealand is a strange market globally as it is both a significant capital importer and also 88% of its lending comes from foreign-domiciled banks (mainly the Big 4 Australian banks).

The RBNZ consultation paper is based on the naïve assumption that the banks would do nothing in response to this additional capital requirements, and that Australian shareholders would blithely fund New Zealand’s aspirations to be the best-capitalised banking system in the world. Under current NZ mortgage prices and assuming higher capital requirements, the banks would be writing mortgages in New Zealand giving returns below their cost of equity: an untenable position.

If implemented this would require each of the Big 4 Australian banks to move ~ $3B in capital to New Zealand. ANZ, as the biggest bank in NZ, would need the greatest amount, but it is also the bank with the largest excess capital position post asset sales in 2017. ANZ’s management said that if these capital controls were implemented, the bank would likely ration credit going into NZ and reprice NZ loans upwards to account for the higher capital charge. On Friday afternoon ANZ share price was impacted as the RBNZ hit back questioning the capital models ANZ is using in New Zealand.

Our take

How to approach investing in Australian banks is one

of the major questions facing both institutional and retail investors alike. We

expect the banks to deliver around 3-5% earnings growth as they face low credit

growth, increased regulatory scrutiny, and the sale of some of their insurance

and wealth management divisions, though there are significant cost-out

opportunities from rationalising their 1,000 branch networks around Australia.

However, if investors

examine the wider Australian market the banks look relatively cheap, are well

capitalised, and – unlike other income stocks such as Telstra – should have

little difficulty in maintaining their high fully franked dividends.

Additionally, their share prices are likely to see support over the next 12 months

as the issues raised in the Royal Commission are addressed. Additionally,

Commonwealth Bank and ANZ are likely to offer share buybacks, as the proceeds

from the sales of non-core assets come through.