Atlas are often asked by clients about the merits of investing in healthcare companies that offer cures, treatments or vaccinations that may both save lives and be very profitable for their investors. Biotechnology and pharmaceuticals[1] are probably among the most exciting and profitable sectors of the market in which to invest. In our view, however, they are also among the most challenging due to diversity of the industry and its complexity.

There are 50 healthcare stocks currently listed on the ASX offering a very wide range of products from medical devices, healthcare facilities to pharmaceuticals and biotherapies.

In this week’s piece we are going to look at investing in healthcare. We will outline the framework that Atlas uses to analyse healthcare companies that invariably have more potential pitfalls for investors than a standard industrial company.

Attractions of investing in healthcare stocks

Not only can healthcare investors gain a warm glow that they are helping humanity investing in companies that may cure life-threatening cancers or the scourge of Covid-19, but successfully developing drugs that respond to such illnesses can also be very profitable. Few investors gain a warm and fuzzy feeling from buying shares in Rio Tinto or Commonwealth Bank! Additionally, many companies in the healthcare sector are growing earnings far above the average of the ASX 200 with consistently high profit margins. Furthermore, companies that sell life-saving therapies to treat haemophilia (CSL) or produce implants that allow children to hear (Cochlear) are likely to see minimal impact on their revenue from macroeconomic concerns such as the US Presidential Election, Chinese bans on Australian exports, or indeed the overall health of the Australian economy.

Binary Outcomes and Extreme Specialisation

When investing in companies like Amcor or Transurban, an investor can make relatively accurate assessments as to the demand for packaging or trips taken on toll roads. By contrast, with healthcare few investors (even at the institutional level) would possess the scientific insight to assess the likelihood of success of different companies’ products in development.

With the biotech and pharma companies the investment case is frequently a binary outcome, namely either:

- the science works and the product is approved for use in major healthcare markets such as the USA and the stock price goes up dramatically, or

b) it fails and the share price goes to zero unless the company can find new sources of funding or new products.

Earlier this week we were looking at Starpharma, a company that has some interesting products in testing designed to enhance the delivery of oncology drugs. In the unlikely event that the investor possessed a PhD in oncology and was able to assess the chance that Starpharma’s products will be approved, that unique investor’s scientific background would be of limited use in assessing the probability that CSL’s cardio-vascular biotherapy CSL112 will be successful in reducing secondary heart attacks. Indeed, the outcomes of many therapeutic development processes are unpredictable, even for specialised scientists working in the field.

Use a framework

When looking at a pharma or biotech company with plenty of promise, but lacking scientific expertise in their exact areas of research, Atlas would break down the analysis into manageable bites by asking the following eight questions:

- What is the quality of management and have they had success before? Previous success in piloting drugs through the torturous and expensive FDA (United States Food and Drug Administration) and TGA (Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration) approval process provides some indication as to the probability of success.

Additionally, we will look at a company’s board for experience working in similar fields to the company’s exact field of expertise, as directors with scientific experience are more likely to be able to probe management. Often companies will have boards with limited direct pharma experience, but with a heavy weighting to directors with experience in finance and law. Directors with experience in these areas may be desirable in a large and well-developed company such as CSL, but less so in a small pharma company.

- How close are the company’s drugs to approval? Looking at where a company’s treatments are up to in the US’s FDA approval process will indicate the level of investment risk. FDA approval is a requirement for sale in the most profitable healthcare market in the world and few companies would only seek Australian TGA approval which would limit sales to the small Australian market.

Companies with at least one product in end-stage trials are safer investments than those just beginning the investigative phases of development. On average it takes 12 years and over US$350 million to get a new drug from the laboratory onto the pharmacy shelf, with a 3% success rate for drugs to move from pre-clinical trials to full approval. We have seen many companies issue exciting prospectuses and raise capital based on the results of their treatment on mice, with minimal further developments many years later.

- What does management own of the company? Here we are looking for substantial skin in the game from management. Ownership aligns the management team with investors, and incentivises them to push the product through the various phases of approval and perhaps towards a trade sale with a large pharma company.

- How big is the addressable market? It is possible for investing in companies treating niche ailments to be profitable, for example Clinuvel does well with their treatments for rare genetic skin disorders. Ideally, however, when investing in healthcare stocks it is preferable to look at those companies operating in illnesses with large addressable global markets such as HIV/AIDS, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, neurological disorders and immunological diseases. Not only is the potential profit pool larger, but companies operating in these areas are more likely to attract a takeover bid from the big global pharma companies looking to restock their pipelines. In some situations, a large global company might make a takeover bid for a smaller company as a way of acquiring research and patents that is easier than going through the more uncertain process of conducting their own research. For example, in 2018 liver cancer therapy company Sirtex received a $1.9 billion bid for the company which was at a 78% premium to closing share price prior to the announcement of the bid.

- Is there third-party endorsement? Third-party support adds to a company’s credibility and can be a positive indicator of future performance. The presence of large corporates or well-known fund managers on a company’s share register is one form of endorsement we look for, especially the multi-national fund managers with vast teams of analysts. An added benefit is that large investors are likely to have deep pockets to subscribe to new equity issues if the company requires additional capital. However, this factor should not be considered in isolation as well-respected managers have backed companies that have gone into administration. Furthermore, an individual healthcare company may in some cases be a very small and ignored portion of an institutional fund with assets in the tens of billions.

- How is the financial strength and cash reserves? Whilst this point is germane to investing in all companies, the length and cost of the approval process for a drug are greater and more uncertain than for a new gold miner or retailer. If the company is required to make multiple dilutionary share issues just to stay in the game, its attractiveness as a potential investment declines. Similarly, if the approval process is slow and the capital markets unfriendly, the company may simply run out of cash prior to their therapies being approved, or may be unable to fund the next stage in the testing process.

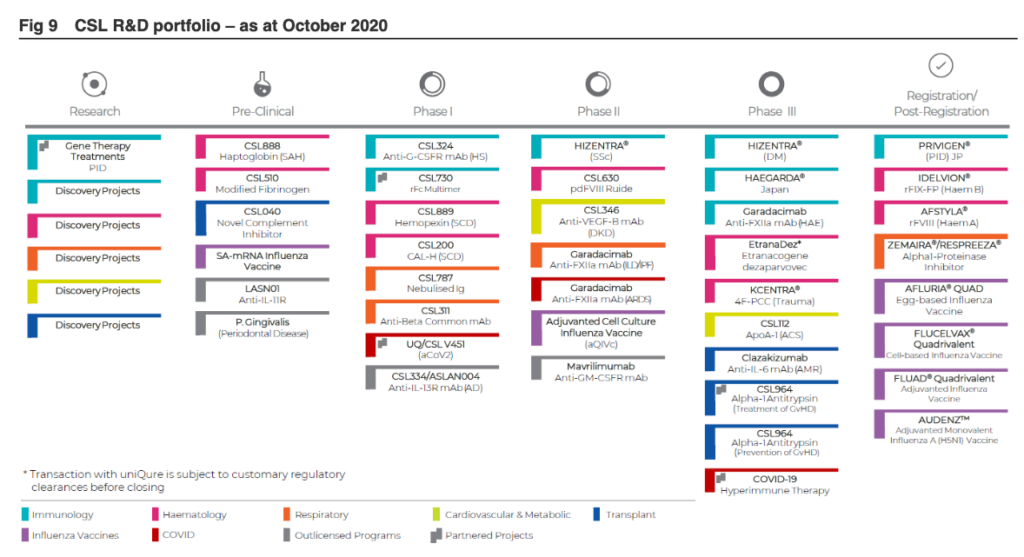

- How diverse is the company’s pipeline? The number of investors that have made considerable gains in one tiny biotech is dramatically outweighed by those that have seen share prices plummet after a company’s only drug failed to win FDA approval. CSL shrugged off the failure of a competitor’s parallel trial of a plasma-derived product used to treat Alzheimer’s, as it had a range of other treatments both in the market and in clinical trials. The below table shows CSL’s pipeline.

8.How is the valuation? Valuation is the last measure that we look at when assessing whether to invest in a biotech or pharmaceutical company. As the vast majority of these companies are either losing money or are barely profitable, traditional valuation methodologies such as discounted cash flows, net asset value or dividend discount models generally require heroic long-range forecasts to derive a positive value. A company that passes a valuation filter is likely to be rejected as an investment if warning signals emerge when asking the preceding seven questions.

Our Take

Analysing a prospective biotech or pharmaceutical company for the first time can be daunting even for very experienced investors. The presentations are frequently full of unfamiliar medical jargon and optimistic accounts of how this particular drug or medical device will be a game-changer for those suffering a particular ailment. Conversely, when investing in banks like Westpac and Citigroup, the financial terminology and core services offered will be very similar, which allows the prospective investor to compare the two different companies easily. We consider that breaking the task down into manageable bites reduces the risk when investing in this potentially very financially rewarding sector allows the investor to compare the investment merits of heterogeneous healthcare companies.

[1] For our purposes the difference between biotech and pharmaceutical companies is that biotechs like CSL use technological innovations based on biological processes to address a health issue, whereas pharmaceutical companies develop therapeutics (medicines) specifically. For example, Pfizer is a pharmaceutical company that employs a chemical-based synthetic process to develop small-molecule drugs, while biotech covers a range of innovations from medical devices to using microorganisms or biologicals (such as blood plasma) to perform a process.