Over the past few weeks there have been several headlines in the financial press discussing investment styles, along the lines of “Is value investing dead?” Such articles generally centre around the triumph of growth investing and the demise of value-style investing. Investors looking for professionally managed equity portfolios face a vast array of options, with the different portfolio managers building portfolios based on their individual investment philosophies or investment styles.

In this piece we are going to look at some different investment styles used to manage equity portfolios, the underlying theories underpinning these investment philosophies as well as the time in the cycle where they tend to outperform. Additionally, we are going to look at the quality style used in constructing the Maxim Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio.

Index Funds

When investing in an index fund (such as Vanguard’s Australian Shares Index ETF) the manager attempts to match the return of the underlying index less a small management fee. Here the manager will automatically buy Fortescue to its current index weight of 1.3% and makes no judgement as to the company’s valuation, or whether iron ore will stabilise at US$120/tonne or fall back to US$60/tonne. If Fortescue’s weight in the index increases due to its share price outperforming, the manager buys more Fortescue and if it underperforms the manager will automatically sell some of the Fortescue shares held by the index fund. As AMP’s fortunes have declined over the past 18 months, index funds have mechanically sold AMP shares in line with its falling index weight, thereby exerting downward pressure on AMP’s share price. The growth in index funds over the past year has increased the impact of momentum and over-valuation, as there is a greater weight of funds automatically buying those companies whose share prices have been rising.

While index funds can be a cheap way to obtain exposure to the equity market, investors are exposed to all companies – good or bad, overvalued or undervalued. For example, in 1987 and 2007 the index contained companies such as Bond Corporation, Qintex, Allco, Babcock & Brown and Centro, all of which subsequently went into liquidation. I observed a more extreme example as a young analyst working in the Canadian market, where telecommunications equipment company Nortel in 2000 comprised 35% of the benchmark Toronto Stock Exchange 300. As an investor in these markets albeit a younger one in 1987, it seemed quite clear before their fall that these were companies with shaky business models reliant on high levels of leverage, and in the case of Nortel irrational market valuation. Not owning companies such as these caused many fund managers to underperform relative to the index, however their investors avoided the losses as these former high-flyers lurched into administration.

Index Funds tend to outperform active managers towards the end of a bull market. At the end of bull markets most fund managers will be reducing risk in their portfolios, increasing the cash weight and moving into safer stocks; whereas index funds will be mechanically buying those stocks whose prices have upward momentum.

Growth Funds

Funds managers using the growth style of investing tend to select securities based more on the brightness of the company’s prospects, rather than the company’s current profits and dividends. Here the growth manager seeks to build a portfolio comprised of companies such as accounting software company Xero or payments company Afterpay, based on the assumption that the market is underestimating their growth prospects.

The rationale is that Xero’s earnings and dividend yield are expected (by the growth manager) to rise rapidly. This justifies buying a company that is trading on a price-earnings multiple of 246 times next year’s earnings per share (EPS) and does not pay a dividend. Unlike an index fund, analysts at growth funds would spend many hours meeting with a company’s management team and industry contacts to understand why the company’s long-term profit growth is likely to exceed the market’s current optimistic assumptions. In 2009, CSL was trading at $31 per share and had earnings per share of A$1.92 and the company was viewed as expensive, trading at a PE (price to earnings) ratio of 16.1 times. In August 2019 CSL is expected to deliver earnings per share of A$6.05 which, based on an initial purchase price ten years ago, puts the blood therapy company on a very reasonable PE of 5.1 times with an 8.8% dividend yield.

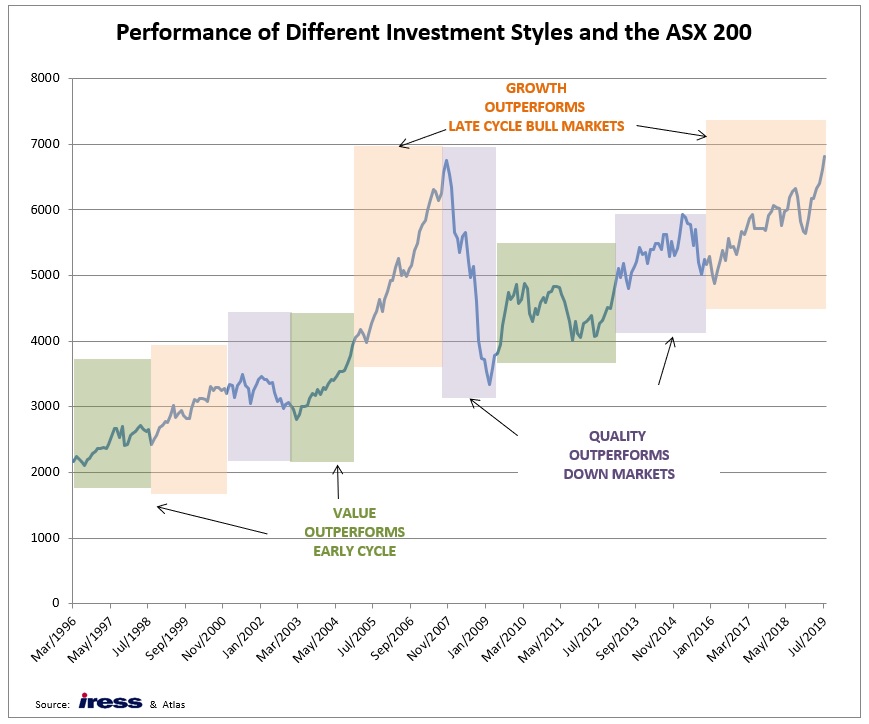

Growth as an investing style tends to outperform during times where the stock market is rising sharply as during these bullish times investors tend to overestimate company earnings and minimise potential problems such as debt refinances and the entrance of new competitors. Also, in the case of growth companies such as Afterpay, when the company’s share price is up 63% in the past 12 months investors don’t care about not receiving a dividend.

Value Investing

Unlike growth funds that tend to buy well-loved high growth stocks, value-style funds adopt the strategy of picking stocks that are trading below their net worth. Benjamin Graham and David Dodd famously developed this style in their seminal investing text from 1934, Security Analysis (not a light read by modern standards with 725 densely packed pages and few graphs). Value investing is based on the concept that undervalued stocks will revert to their intrinsic value, thus allowing the investor to buy (for example) $1 worth of assets for 80c.

Characteristics of this investing style include buying companies that are trading on a low price to book value, low PE ratio, or indeed buying companies whose liquidation or wind-up value is greater than their current market value. A classic example of a stock that would have featured in many value-style portfolios over the past year was Telstra. In July 2018 Telstra was trading at $2.60 which equated to 13 times its projected earnings per share and with a dividend yield of 7%. Here the market was concerned about increasing competition in the mobile phone market in Australia and the impact of the NBN on profit margins. Over the past year Telstra’s share price has rallied to almost $4 due to a combination of decreasing price competition in mobiles, and government decisions to block rival TPG from both building a 5G network (using Huawei technology) and merging with UK-based Vodafone. Telstra currently trades on a PE ratio of 25 times with a 4% dividend yield.

Typically, a value-style fund will have a lower price to earnings ratio, lower beta (a measure of volatility), and a higher dividend yield than a growth-style fund, with greater exposure to more mature companies. One of the dangers of value-style investing is being attracted to companies that are “value traps”, namely those that have a high (albeit unsustainable) historical dividend yield and low PE ratio as they operate in a declining industry. While department store owner Myer has recovered in 2019, this company is viewed by many to be a value trap.

Value funds often outperform during a recovery as the manager is likely to own disliked companies that are priced on low PE multiples as the market views that the company may go into administration or will only see low to negative growth. When the market’s views on the prospects of these companies are proved to be too pessimistic, the share prices of these value-style companies can see a substantial re-rating. Myer is a great example of a value stock who’s share price recovered sharply from 36 cents in February 2019 to 72 cents in April!

Quality Investing

Following the Dot Com Bubble of the early 2000s and the aftermath of the GFC, investors have begun to pay more attention to the quality of a company, rather than just its raw earnings multiple or dividend yield. This approach or style has been called quality investing and focuses on hard factors such as the quality of a company’s earnings or balance sheet, along with softer factors such as the quality of corporate governance and transparency of information being given to investors, while still seeking to buy companies that are undervalued. Although their strategy shares many characteristics with value investing, quality-style fund managers are prepared to tolerate paying more for companies with higher quality recurring earnings streams and tend to avoid very cheap companies that are in the process of restructuring. This is the approach we use in managing the Maxim Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio.

Quality investing seeks to avoid risky stocks and focus on owning both high-quality companies and stocks with improving quality. In the case of improving quality, here the market may see a company as low quality, when in fact the underlying fundamentals of that company are improving. For example, in early 2017 private health insurer Medibank was added to our portfolios. At this time, we considered that the market was not pricing the potential profit uplift that Medibank’s management could generate from cutting out costs and inefficiencies that crept in over the decades of government ownership. As the market recognised the improving quality of Medibank and the steadily rising profit margins from reducing costs, the share price has moved steadily upwards. We do however recognise also that the Federal Coalition’s victory in May has improved the company’s prospects.

Quality style fund managers tend to outperform during market falls and in the early stages of a recovery, as investors abandon stocks whose business models now look fragile in a harsher economic environment. During times of market turbulence, companies offering recurring high-quality earnings derived from selling non-discretionary goods or services look very attractive, with a high sustainable dividend yield cushioning falls in their share price.

Our Take

In managing the Atlas Australian Equity Funds, we strongly favour the quality investing approach which reflects experience in managing funds across a range of different market conditions including the Tech wreck in North America in 2000, the GFC in 2008 and the collapse of commodity prices in 2015/2016. After investing in a few cheap companies earlier in my career that ultimately turned out to be “value traps”, I prefer paying a higher earnings multiple for companies that offer greater earnings and dividend certainty. Nevertheless, when investors choose a fund manager, the manager’s style must match the investor’s goals and their investing temperament. If an investor is looking for a fund that focuses on owning high reward (and risk) tech stocks, investing with a manager looking to deliver low volatility and higher dividends is likely to be unsatisfying.