In the press, large movements in the Australian dollar are often erroneously presented in the press as a vote of confidence in Australia as a nation or the management (or mismanagement) of our elected leaders. A falling Australian dollar is often viewed as a negative event, raising the cost of online purchases, imported cars and overseas travel.

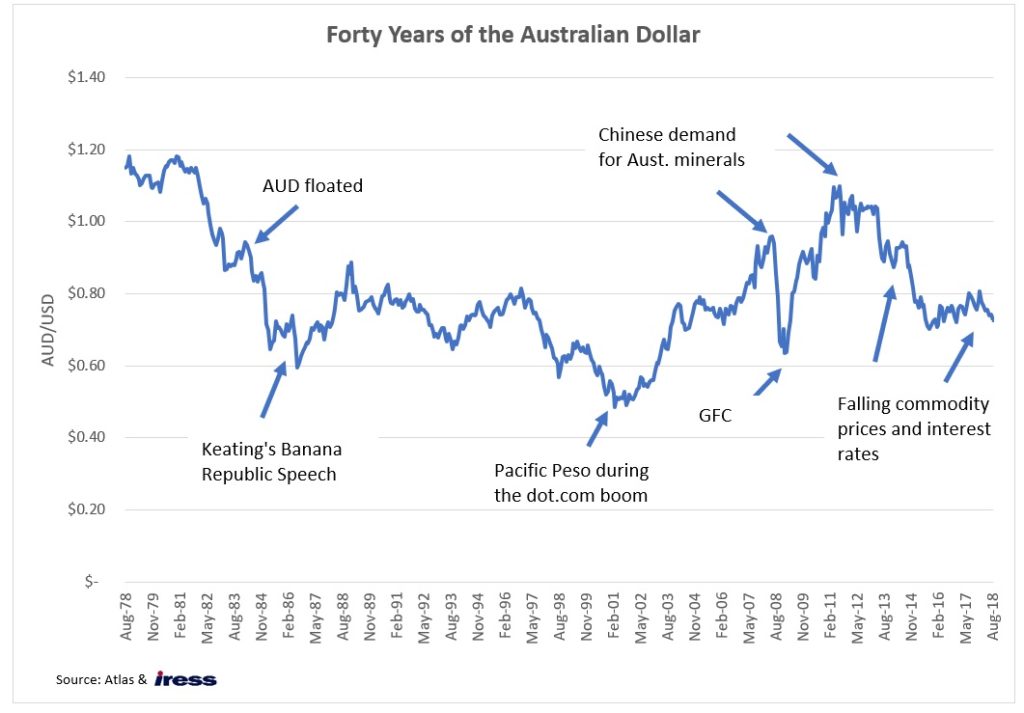

Over the last year, we have seen the AUD fall 8% vs the USD, continuing the volatility in the AUD that we have seen over the past decade since the AUD peaked at 1.10 vs USD in 2011. Over 2018 we had seen the AUD slide downwards from a peak of 0.81 in January to 0.725 as uncertainties over the leadership of the country have increased. Political instability is likely to continue to weigh on the AUD in the short to medium term, as over the next year Australia faces a National election and a likely change in government to a party that has few business or investor-friendly policies.

In this week’s piece we are going to look at currencies, the AUD and in particular the winners and losers from currency movements.

Fixed Rates

For much of the last 200 years currencies have been fixed either against another stronger currency or commodity such as gold. For example, following the second war the Bretton Woods agreement pegged currencies against the USD, which was fixed to gold at the rate of US$35 per ounce.

When a country has a fixed currency and faces adverse economic conditions, their treasury inevitably uses the nation’s stock of foreign currency reserves to prop up a faltering exchange rate. The outflow of foreign currency reserves occurs as investors seek to exit and sell the county’s currency which is viewed as overpriced based on the changing economic circumstances or market sentiment. A great example of this occurred in Russia in 2008, which saw Russia chew through US$200 billion in carefully hoarded foreign currency reserves in a futile attempt to defend the value of the rouble before eventually devaluing the exchange rate.

Additionally, fixed rates can attract the attention of speculators that may look to profit from a forced reset in the exchange rate, where the rate is perceived to be fixed at a rate higher than the currency’s fundamentals. For example, in 1992 the GBP was set at a rate of 2.7 DM to the GBP as part of the European Rate Mechanism, fundamentally this over-valued the GBP as it the UK’s inflation rate was three times that of Germany’s. Speculators famously led by George Soros shorted the GBP, after spending large amounts of foreign currency reserves defending the GBP and raising interest rates from 10 to 12%, the GBP was ultimately devalued, netting Soros’ fund a profit of GBP1 billion.

Floating Rates

In the 1970s as a result of inflation induced by spending in on the Vietnam war, the US abandoned fixing the USD to gold and allowed the USD to float freely in line with market demand. The free float of the USD eventually forced other major currencies to follow suit, with the AUD switching to a floating rate in 1983.

By allowing its currency to float freely, a country loses the ability to control its exchange rate, but it gains control of its monetary system. Before 2000 (when the Greek Drachma was fixed to the €), the current Greek debt situation would have arguably been much less painful to the Greek economy. The current Greek debt crisis would have seen the Drachma being sold down heavily, thus making summer holidays on the Aegean and Greek olive oil much cheaper than similar products offered by Italy or France.

History of the AUD

In 1983 when the Hawke government came into power, one of their first decisions was devalued the AUD by 10% and float the Australian dollar, assuming that this action would cause the AUD to fall and improve our international competitiveness and stimulate the export sector. Before 1983, the value of the AUD was set each day by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Federal Government and either directly pegged to the foreign currencies such as the GBP or USD or pegged to a trade-weighted basket of currencies.

Corporations had to apply to the RBA to buy foreign currencies to buy imported goods or make investments offshore, with the RBA selling the company USD or GBP in exchange for their AUD at the official fixed rate.

Two floors of the RBA Building in Martin Place were occupied by Exchange Control staff whose job was to make it hard and discouraged for Australian businesses and investors wanting to invest offshore. While this sounds archaic, this level bureaucratic obstruction may have prevented BHP US shale gas debacle or Wesfarmers UK hardware expedition, both of which resulted in significant transfers of wealth from Australian shareholders to companies domiciled in the US and the UK.

Since floating in 1983 the AUD/USD has averaged 76c. However, the AUD was in a downward trajectory from 1983 to 2002. This was broadly due to Australia’s higher relative inflation rate. The strength in the AUD over the past ten years has been a result of China’s industrialisation and its unprecedented associated explosion in demand for Australian minerals since China’s integration into the global economy after joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001. More recently the interest rate differential between Australia and the US and Europe has boosted the AUD; though rate cuts since 2011 and higher US rates have closed this gap. In the medium term, we would expect the AUD to move towards fair value based on purchasing power parity, which we estimate, is approximately US$0.66.

WINNERS

The companies that are likely to benefit from a weaker AUD fall into four categories;

- Import substitution: Companies that produce something in Australia and compete with the now more expensive imports such as steel (BlueScope), fertiliser (Incitec Pivot) or tourism (Crown).

- Exporters: Companies that have production costs such as wages in Australian dollars but sell a commodity globally like iron ore that is priced in USD (Rio Tinto) or Grange Hermitage wine (Treasury Group). Here a falling AUD translates into higher revenue for the same quantity of goods sold.

- Companies with inflation linked-pricing: When a falling AUD results in inflation, companies like Transurban should see an expanding profit margin. Here their road tolls will increase with inflation, while a proportion of these companies’ costs remain fixed, thus resulting in higher profits.

- Offshore Operations: The falling AUD also benefits companies with substantial offshore operations such as CSL, Atlas Arteria and Unibal-Rodamco-Westfield, as their USD or Euro denominated earnings are worth more when translated back into AUD for Australian investors.

Losers

The companies that are likely to hurt from a weaker AUD fall into three categories;

- Resellers: The companies that are typically hurt by a falling AUD are those that buy goods offshore for resale to Australian consumers such as retailers Myer and JB Hi-Fi. Here Australian consumers wages are not impacted by a fall in the currency, but a new iPhone or LED TV’s cost has gone up.

- Users of foreign content in their production process: Similarly, a falling AUD presents a challenge for companies like Qantas and Seven West Media that earn revenue in AUD from domestic consumers, but have significant USD-denominated costs such as aviation gas or television series produced in the USA.

- Unhedged borrowers of offshore debt: Further, companies that have significant un-hedged USD borrowings such as Boral will see their interest costs increase, especially if the company does not have USD earnings to service their debt. This situation occurred in 2010 and required Boral to raise $490 million to keep the company within their debt covenants.

Our Take

We expect the AUD to continue to trend down towards 66c in-line with purchasing power parity, diminishing interest rate differentials between Australian and other Western economies and expected further falls in commodity prices. Accordingly, we have structured the portfolio to benefit from a falling AUD. One additional benefit in having a strong bias towards companies with earnings offshore is that the variability of domestic political decisions and the uncertainty brought on the turnover in leadership will have less of an impact on profits and dividends.