Unlike industrial companies such as Amcor or Transurban, profits for mining companies are inherently cyclical. The earnings from mining companies are subject to booms and busts, largely outside the control of their management teams. This occurs as ultimately any company producing a commodity is a “price taker” not a “price maker”, as there is no difference or brand premium between a pound of copper mined in Australia or in Chile. Due to the nature of the cycle, we see that mining stocks should not be viewed as buy and hold forever. Rather, investors should pick and choose their entry points based on where they consider that minerals are in the mining cycle.

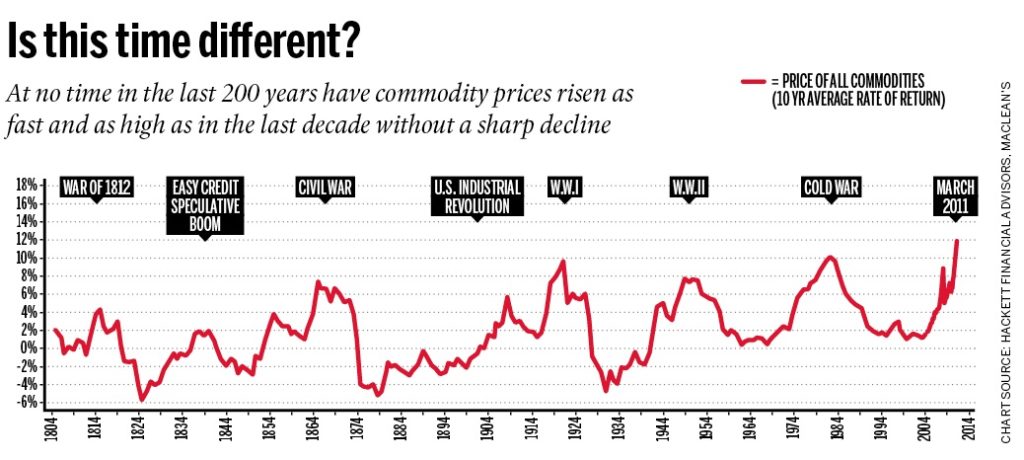

In this week’s piece we are going to look at the five different points of the mining cycle and where in the cycle Atlas perceive that commodities are currently positioned. The chart below shows the commodity cycles over the past 200 years, with the peaks coinciding with major wars or industrialisations of large economies.

1. Demand for commodities drives up prices

In the short term, supply is relatively fixed for most commodities as miners have optimised their mines for a specific level of production and minimal exploration during the lean times has run down ore reserves. At stage 1 of the cycle memories of the previous bust are still pretty fresh, and there is likely to be an under supply of personnel such as mining engineers. Additionally, the few surviving mining services businesses and contractors are likely to have minimal spare capacity which could allow production to expand quickly. Further, management teams in the mining companies are unwilling to greenlight capacity expansions until they become convinced that higher commodity prices are permanent.

In recent times this occurred in 2004 and 2005 as the industrialisation of China delivered a new buyer for Australian materials. This saw copper increase from $1 per lb in 2004 to close to $4 per lb in 2008 as supply was relatively static despite increased demand.

2. New Exploration undertaken to add to supply and Takeover activity surges

At stage 2 of the cycle, management teams at the mining companies are likely to be running existing mines at full capacity and have developed some confidence that elevated prices will persist for some time. This incentivises new exploration and capex is allocated to bring previously uneconomic discoveries into production.

At this stage we also see surging M&A as companies use excess capital built up in Stage 1 to buy growth which can be delivered faster through a takeover than developing new mines. An example of this was the 2007 acquisition of Alcan by Rio Tinto for US$38 billion.

3. New mines start producing at the same time results in supply being greater than demand

Due to the long lead times, in my observation a range of projects tend to hit the marketplace at almost the same time. Additionally, from speaking to resource CEOs during stage 3, each of them are invariably convinced that they have the best project and that rival projects won’t go ahead or get financing. Quite often a range of similar projects are all developed, with banks falling over themselves to provide finance them. Prior to stage 3 these projects look to be quite low risk with short payback times if prices are maintained (which they won’t be). Further, the costs of these projects are inevitably higher than originally forecasted due to the competition for scarce resources such as skilled labour and capital goods. A great example of this can be seen in the decision of Santos, Origin Energy and BG to construct three LNG gas projects simultaneously at Gladstone in Queensland.

The long lead times between development and first production can result in new mines coming online in market conditions quite different from when they were first conceived. A great example of this is Oz Minerals’ Prominent Hill Copper Mine which started being developed in 2006, and then came online 3 years later in 2009 at a cost of $1.2 billion. During the construction process the Copper price had fallen from $4 per lb to $2 per lb at the time of mine opening. Similarly the US$10 billion Roy Hill iron ore mine started initial developments in 2011, with full production only being achieved in 2017.

Due to the debt burden generally incurred to develop projects, despite the fall in commodity prices at stage 3 of the cycle, many mines will boost production to cover their cash costs (including debt repayments), driving down industry margins. Given the cost of actually closing a mine (redundancies and break fees for contracts written with rail and equipment suppliers), most mining executives are reluctant to put their projects on care and maintenance to remove capacity from the industry. We saw this in 2014 and 2015 where a range of smaller Australian iron ore such as Atlas Iron and BC Iron were mining iron ore, yet were losing close to US$20 on every ton of their ore shipped, with the iron ore price at $50/t. Additionally, higher cost Chinese state-owned iron ore mines continued production despite losing money on every ton, due to the perceived political imperative to maintain employment.

4. High cost and less efficient mines close and late cycle projects abandoned until next boom

At this stage of the cycle the canaries in the metaphorical coal mine are the contractors servicing the miners. In an effort to avoid the finality of shutting production, costs are pared back with the services businesses serving the mines the first to feel the pinch. Exploration budgets are slashed and expansion plans put on ice. These actions can push highly geared services companies such as Boart Longyear into administration. Larger mining services companies such as Downer tend to see large declines in profit as services are taken in-house by the miners and bull market contracts are re-written.

The next step at this stage is for the higher-cost producers to mothball their mines in an effort to conserve corporate cash and keep the company as a going concern. In 2015 a range of higher cost iron ore producers such as Atlas Iron, BC Iron, Arrium and Mount Gibson shut production, some of which have since been reopened. The more established mining companies at this stage will slash dividends (BHP in 2016) or raise capital to stave off worried bankers (RIO in 2009).

Complex late cycle projects that get deferred included Rio Tinto’s controversial Simandou iron ore project in Guinea which was shelved in 2016 due to concerns about the iron ore price. To develop this mine, Rio Tinto would have needed to construct both new 670-kilometre heavy freight rail line to transport iron ore shipments from Guinea’s Simandou Mountain range to the coastal city of Conakry and a sea port to load this ore onto ships. Despite the size and quality of this ore body, this would have been a risky and costly venture at this stage of the mining cycle.

5. Capitulation

At this stage sustained falls in commodity prices forces a range of second and third tier miners into administration with ownership transferring from equity to debt-holders. The remaining lower cost miners going into survival mode, focusing in on conserving cash. Exploration will stop, as excess supply is now expected to continue almost indefinitely. Here a range of professionals such as mining engineers and resources analysts at investment banks will start to leave the industry. The last part of this circle of life is the conversion of the ASX-listed shells of mining companies into “new economy” companies to speed up their listing process. For example, in the late 1990s the ASX-listed shells of the defunct mining and exploration companies from the 1980s were reborn as “dot.com” companies.

Where are we now?

Every cycle broadly follows the curve, yet looks a little different when you are in the eye of the storm. Two years ago, in January 2016 it strongly appeared that we were in stage 4 and staring down the barrel of a long winter for commodities prices, but 2017 did not follow the expected script as commodities prices strengthened. This occurred due to China’s efforts to stimulate their property sector, slightly stronger growth in the developed world, and supply disruptions to mines such as Samarco in Brazil. Additionally, structural reforms in China aimed at reducing pollution and improving the quality of growth have increased demand for higher quality grades of commodities.

The 2017 recovery in commodity prices has pushed us back into the mid cycle, though both companies and the investment community are very cautious. There are few new IPOs coming to market outside the exotic commodities linked to electric vehicles, minimal significant corporate takeovers being announced, and expansion activity remains subdued. In the upcoming February, reporting season will show very healthy mining company balance sheets which will hopefully result in improved returns for shareholders, rather than value destructive empire building.

We are more cautious than most, as being pushed back into this favourable stage has occurred to some degree by the desire of the Chinese government to stimulate their property market. Chinese economic policies will not always favour Australian investors and a cooling Chinese property market (as breaks are applied) could have a chilling impact on commodity prices.