NoCookies

To use this website, cookies must be enabled in your browser. To enable cookies, follow the instructions for your browser below. Facebook App: Open links in External Browser There is a specific issue with the Facebook in-app browser intermittently making requests to websites without cookies that had previously been set.

Category: Uncategorized

Bank reporting season: the good, the bad and the ugly

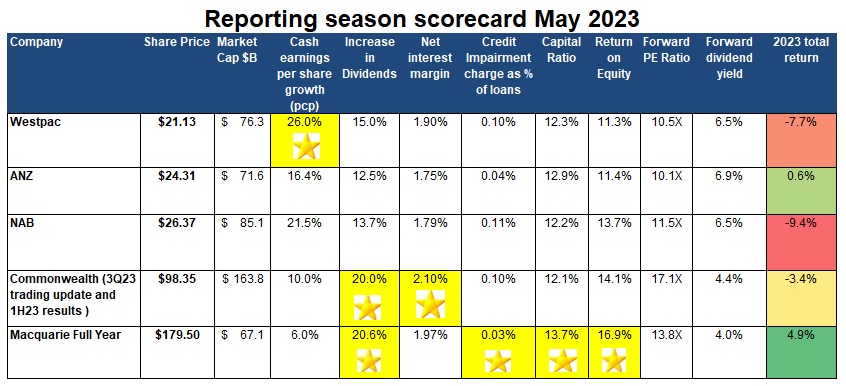

Over the past week, we have seen the major banks report results for the six months ending March 2023 and, in the case of Commonwealth Bank, provide a trading update for the third quarter of their 2023 financial year. In this piece, we will look at the themes in the approximately 1,000 pages of financial results released over the past seven days, awarding gold stars based on performance over the last six months. The results were better than expected, and most banks rewarded shareholders with dividends per share above pre-Covid levels.

This article originally appeared in Firstlinks

The shape of the loan book

A new banking metric for investors in 2023 has been the composition of the bank’s mortgage book 1) the split between fixed and floating loans and 2) when these low-rate fixed loans, primarily written in 2020 and 2021, will convert into higher rate variable loans.

During previous interest rate tightening cycles such as 1998/2000 and 2006/08, the mortgage book primarily comprised variable rate loans. Consequently, moves by the RBA to control inflation by raising rates were swiftly transmitted into the economy via higher mortgage payments.

However, according to the RBA, fixed-rate loans peaked in 2022 at close to 40% of outstanding housing credit, rendering monetary policy to control inflation a very blunt tool. The RBA’s low-cost Term Funding Facility encouraged this fixed-rate lending, which allowed banks to borrow between 0.1% and 0.25% for three years. The Term Funding Facility saw $188 billion borrowed at low rates until it was closed in June 2021, with a final maturity date of June 2024. A more accurate picture of bad debts will emerge when these lower fixed rate loans have converted into higher variable rates.

In March 2023, for CBA, NAB and Westpac, approximately 33% of their loan book was fixed-rate loans, with the largest cohort of loans set to expire over the next four months. Conversely, ANZ has a much lower exposure to the ‘fixed rate cliff’, with only 22% of their mortgage book exposed to fixed-rate loans in March 2023. We are hesitant to award a Gold Star to ANZ for this low exposure to the ‘fixed rate cliff’, as 2020 and 2021 coincided with ANZ losing market share and shrinking their loan book due to internal issues in processing an unanticipated large increase in borrowing across the system.

No Stars Awarded

Net interest margins

Net interest margins (NIM) were the major topic during the May banks reporting season and the focus of questions posed to management, particularly the exit NIM or the profit margin that the banks were making on loans written at the end of March 2023. Banks earn a net interest margin [(Interest Received – Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] by lending out funds at a higher rate than by borrowing these funds from depositors or wholesale money markets.

Rising net interest margins have been a source of optimism for the banks since the RBA started raising rates for the first time since November 2010 last May, moving from the cash rate from 0.1% to 0.35% (currently 3.85%). Falling interest rates reduce the benefits banks get from the billions of dollars held in zero or near-zero-interest transaction accounts that can be lent out profitably and have seen a decade-long fall in net interest margins.

However, in a rising rate environment, this pool of deposits in transaction accounts and term deposits will constitute a cheap funding source and allow bank net interest margins to expand. Over the period ending September 2022, the banks saw net interest margins expand for the first time in a decade. However, many questioned whether margins have peaked as banks slowly increase the interest rates paid on deposits due to political pressure and competition for deposits. CBA posted the highest net interest margin for the first half, with 2.1%, and the other banks reported steady to rising net interest margins for March 2022. NAB was sold off heavily on its results day after reporting that its margin had fallen in the second quarter of 2023.

Capital

In 2023 all banks have a core Tier 1 capital ratio above the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) ‘unquestionably strong’ benchmark of 10.5%. This allowed Australia’s banks to enter the 2022/23 rising rate cycle with a greater ability to withstand an external shock than in 2007 going into the GFC, where their Tier 1 Capital ratios were around 6%. For investors, this means that the banks have more capital backing their loans and a lesser chance that investors will face dilutive equity raisings if bad debts spike.

Interestingly, Westpac and NAB faced questions on the management calls on why they were not conducting share buy-backs to return excess capital to shareholders, with Westpac deferring the decision until October. We would be surprised if APRA granted approval for banks to conduct share buy-backs today, given the uncertain impact of significant numbers of borrowers switching from cheap fixed-rate loans issued in 2020 and 2021 to higher-rate variable loans in 2023. Macquarie Bank held the highest level of capital in March 2023, with ANZ’s high capital level elevated due to a capital raise in August 2022 to buy Suncorp Bank, a deal yet to be consummated.

Show me the money!

Our table shows that all banks increased their dividends in the most recently completed reporting season. Here, bank investors benefited from the combination of sharply rising profits, benign bad debts, excess capital and a reduced number of shares outstanding due to buy-backs in 2022 from NAB, CBA and Westpac. Westpac was the only bank in March 2023 to pay a dividend per share lower than what was paid in the corresponding pre-Covid 19 period in 2019, though ANZ’s dividend was 1 cent higher and NAB’s matching. CBA and Macquarie posted large 20% dividend increases, reflecting record profits for both banks. If continued low unemployment and minimal falls in house prices keep bad debts from spiking, investors may see rising dividends and, indeed share buy-backs at the full year 2023 results.

Bad debts

After net interest margins, the second most important number in every bank’s financial report in 2023 was bad debts, with investors looking to see if rising interest rates caused losses on loans. Low bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay and that the bank will incur a loss on the loan. Since the 1991 recession, the normalised long-term level of bad debts has been around 0.30% of total loans for Australia’s banks.

Bad debts remained low in 2023, with all banks reporting negligible loan losses; Macquarie Bank reported the lowest level of bad debts, with 0.03% narrowly ahead of ANZ. However, we do expect bad debts to rise in the future and recognise that March 2023 is too early for the banks to show significant stress in their lending book, particularly considering the low unemployment rate and higher weighting towards fixed-rate mortgages in 2022/23 than was present in other tightening cycles.

Reports of demise greatly exaggerated

The last four years have been very eventful for bank shareholders, with each year bringing a new set of worries predicted to bring the banks to their knees. In 2019 the fears centred around neobanks such as Xinja, 86 400 and Volt using fintech to reinvent retail banking and take significant market share off the major banks, with the neobanks unencumbered by legacy systems and branch networks. Over the period 2021 to 2022, these neobanks gradually handed back their banking licences and returned deposits to customers. 2020 saw capital raisings from NAB and Westpac missing their first dividend since the banking crisis of 1893, as experts forecasted 30% declines in house prices and 12% unemployment!

2021 saw the banks grappling with zero interest rates and APRA warning management teams about the systems issues they may face from zero or negative market interest rates. A problem that seems quite comical today. 2022 saw the RBA raise the cash rate from 0.10% to 3.10%, the most rapid tightening ever from Australia’s central bank. In 2023, the concerns have switched to the impact of sharply rising interest rates on bad debts and the upcoming ‘fixed rate cliff’.

Our take

The May reporting season showed that Australia’s banks are in good shape and face a better outlook than many sectors of the Australian market, despite rising interest rates. The major banks face the next few years in a far stronger position than they went into 2007. The unemployment rate is 3.5%, significantly less than it was going into the last rate tightening cycle.

While rising interest rates will undoubtedly cause stress to many borrowers over the next 12 months, so long as employment remains strong, mortgage repayments will stay high and bank bad debts low. However, we expect the outlook for consumer discretionary stocks such as Flight Centre, Harvey Norman and AP Eagers to deteriorate as spending on Bali holidays, televisions and new cars are diverted to service higher mortgage payments.

Atlas expects the banks to outperform in the near future, enjoying a tailwind of a rising interest rate environment and high employment levels, which will see customers make the new higher loan repayments. With an average grossed-up yield of +7% and lower-than-expected bad debts, bank shareholders will be rewarded for their patience and for ignoring the current market noise.

Discussing the Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio with Robert Dekkan – Strat Wealth

April Monthly Newsletter

- April saw global equity markets rally between 1% and 3% on market views that the interest rate tightening was coming close to an end and slowing inflation globally. Australian shares benefited from stronger consumer sentiment and an increase in national house prices, which in hindsight, contributed to the RBA’s surprise decision in early May to tighten interest rates after pausing at their April meeting.

- The Atlas High Income Property Fund gained by +3.3% in April, with the share prices of many companies held in the Fund starting to recover from the falls seen during the market panic in March. The falls in March were based on the assumption that property and infrastructure trusts could not increase revenues with inflation, and all had short-term variable rate debt. Currently, the average weighted debt maturity across the Fund is 4.7 years.

- The extreme market volatility over the past twelve months is very unusual and a result of a normalising of interest rates and, for many investors, their first experience with inflation. While exasperating, the Fund is populated with companies positioned to navigate changing market conditions with 1) long-term fixed-rate debt, 2) revenues tied to inflation and critically, and 3) valuations backed by actual comparable sales in the direct property market and not works of fiction.

Go to Monthly Newsletters for a more detailed discussion of the listed property market and the fund’s strategy going into 2023.