In the travel sections of newspapers there frequently appear articles with titles such as Top 7 Overseas Travel Scams (and How to Avoid Them). However, Atlas see the biggest cause of Australians losing money overseas is not pickpockets, dodgy taxi drivers, or pre-damaged jet skis, but rather ill-conceived offshore acquisitions by Australian corporates.

Last Friday the latest of these came to an end with Wesfarmers exiting their UK Hardware operations. Over the two and a half years of ownership, this adventure cost Wesfarmers shareholders A$1.7 billion. What is worse is that for shareholders of Wesfarmers, booking the loss and selling these operations for one pound is a good outcome as it avoids significant closure costs. At Atlas, based on bitter experience we are very sceptical about offshore acquisition strategies embarked on by Australian corporates. In this week’s piece, we are going to look at offshore expansion by Australian companies.

Why Australian companies expand offshore

The main reason expounded by Australian corporates for offshore expansion is to gain access to larger pools of potential customers for the purpose of driving earnings growth. In many industries, Australian companies operate in oligopolies or are constrained by government regulators such as the ACCC (Australian Competition & Consumer Commission) from growing rapidly through either price competition or acquiring competitors.

In the banking or grocery industries, neither Westpac nor Woolworths are able to take market share from competitors by dropping prices, as their competitors will immediately match their moves. Similarly, a move by Westpac to acquire the smaller Bank of Queensland would have difficulty getting approval from the ACCC.

Other reasons touted for global expansion are access to new technologies and diversification, since business or regulatory conditions in certain foreign markets may not be correlated with those in Australia. For example, Sonic Healthcare is not likely to face simultaneous fee pressures in their pathology businesses in the USA, Australia and Germany. Where management teams are under pressure and incentivised to grow earnings each year, it is understandable that they could be seduced by an investment banker in a two-thousand-dollar suit selling dreams of global expansion.

We will now go on to examine some of the mistaken assumptions that motivate international expansions.

Wrong move 1: We are dominant in Australia, so we will dominate the world

We see that this is the most common mistaken assumption made by Australian corporates venturing offshore. Arguably this was the rationale motivating Wesfarmers when they purchased the number two player in the UK hardware market in 2016. In Australia, Bunnings dominates the $48-billion hardware sector and earns an EBIT margin of 14%, whereas Bunnings’ equivalent in the UK – Kingfisher – has an EBIT margin of 7% in a more competitive and crowded market. Firstly, Australian entrants will often face higher levels of competition in new markets. Furthermore, a successful strategy in Australia will not necessarily resonate with foreign consumers. In the case of Bunnings UK, large BBQs and cheap power tools that sell in Sydney were a surprise to UK shoppers entering a Homebase store in the UK looking for Laura Ashley homewares.

Other examples of this factor can be seen in IAG’s entry into the UK general insurance market after buying the country’s eighth largest motor insurer. Ultimately this adventure cost shareholders $1.3 billion, as IAG found the UK insurance market far more competitive than Australia where IAG, Suncorp and QBE have a 70% market share. In a similar vein, NAB in the late 1980s and 1990s acquired banks in Northern England, Ireland and the USA, based on the strategy that their dominance in Australia would translate into other parts of the English-speaking world. Ultimately NAB was unable to run the dispersed set of financial services businesses from Melbourne and this adventure cost shareholders billions, though it would have been costlier had NAB not sold their Irish banks to Denmark’s largest bank just prior to the GFC.

However, it would be disingenuous not to mention that foreign companies also make this same mistake in buying domestic assets at high prices off canny Australians. Japan’s Kirin Breweries and UK’s SAB Miller have written off portions of the Lion Nathan and Fosters brewing assets, as sales of iconic Australian beers such as Tooheys and Victoria Bitter have declined with drinkers turning to smaller craft beers.

Wrong move 2: Let’s try something new

This version of an offshore misstep generally occurs when an Australian corporate with excess cash is presented with an opportunity to grow earnings by investing in a new technology in a foreign market. Typically, this involves buying assets from local players who typically have a better grasp on what the assets are actually worth. A great example of “Let’s try something new” has been BHP’s investments in US onshore shale gas in 2011 and 2012. BHP acquired assets of US$4.75 billion from Chesapeake, and US$15 billion for Petrohawk. BHP at the time was flush with cash due to a surging iron ore price. However, extracting shale gas in the US is more of a small scale modular process compared with BHP’s massive iron-ore and offshore LNG projects. Furthermore, BHP’s purchase was made at peak oil prices. In 2018 BHP is in the process of extricating themselves from these acquisitions, having already written off US$13 billion of this investment.

Wrong move 3: Sort of similar to something we already do

This acquisition mistake is a close cousin of “let’s try something new” in that the acquisition is made in an area close to the company’s core area of competency and presented to investors as a low-risk form of offshore expansion. Fletcher Building’s purchase of the Cincinnati-based Formica in 2007 for US$ 700 million from private equity was touted as a logical extension to the company’s decorative surface laminates business. In hindsight, this acquisition was made at the peak of the US housing construction cycle for a business that faced ongoing production issues due to site consolidation.

Slater+ Gordon’s acquisition of Qunidell’s professional services division in 2015 for A$1.2 billion also falls into the category of “Sort of similar to something we already do”. Whilst this infamous acquisition made Slater+Gordon the number one personal injury law firm in the UK, it also added claims management companies, insurers and insurance brokers – businesses somewhat adjacent to the company’s core litigation practice. Arguably this move helped contribute to equity holders losing 99% of the value of their investment in the company as it both burdened the company with too much debt and bought a business without undertaking sufficient due diligence.

Shortly after the purchase of Quindell, the UK government announced plans to limit the proceeds from personal injury claims and Quindell came under investigation for accounting practices that inflated earnings. See Jonathan Shapiro’s fine analysis of this transaction in Sowing the seeds of Slater & Gordon’s market demise.

No discussion of poor acquisitions would be complete without including Rio Tinto’s 2007 acquisition of Canada’s Alcan for US$38 billion, which manages to put tick most boxes of a poor offshore expansion. This acquisition arguably was made to fend off a takeover from BHP and led to Rio acquiring smelters in exotic places such as Iceland (“Sort of similar to something we already do”) and engineered products and packaging (“let’s try something new”). Ultimately US$30 billion of this acquisition was written off and resulted in a highly dilutive equity issue in 2009.

Offshore acquisitions that worked

It would be wrong to claim that all offshore acquisitions end in tears for Australian investors. A number of Australian companies have made major offshore acquisitions that have driven earnings growth for a number of years and propelled the company into a major global player in their industry. Amcor has leveraged a range of successful acquisitions to become one of the largest manufacturers of flexible packaging and rigid plastics, ironically making their most successful acquisition from Rio Tinto.

Similarly, CSL made major acquisitions in 2000 and 2004 in Switzerland and Germany and is now the largest global producer of blood plasma-derived medicines. Computershare has grown through acquisition to become one of the largest global share registry businesses, successfully buying and improving the profitability of various global banks’ unwanted registry businesses. Sonic Healthcare has made 50 acquisitions over the past 20 years in Europe and the US. Sonic’s shareholders have enjoyed rising profits due to doctors requesting greater numbers of tests per patient and being able to run higher volumes through their increasingly automated labs.

The common theme through these successful offshore expansions is that the Australian companies have focused on a particular niche where the Australian company has some form of comparative advantage. This is very different from buying foreign banks, where the Australian company brings no intellectual capital or technology to the table, only capital!

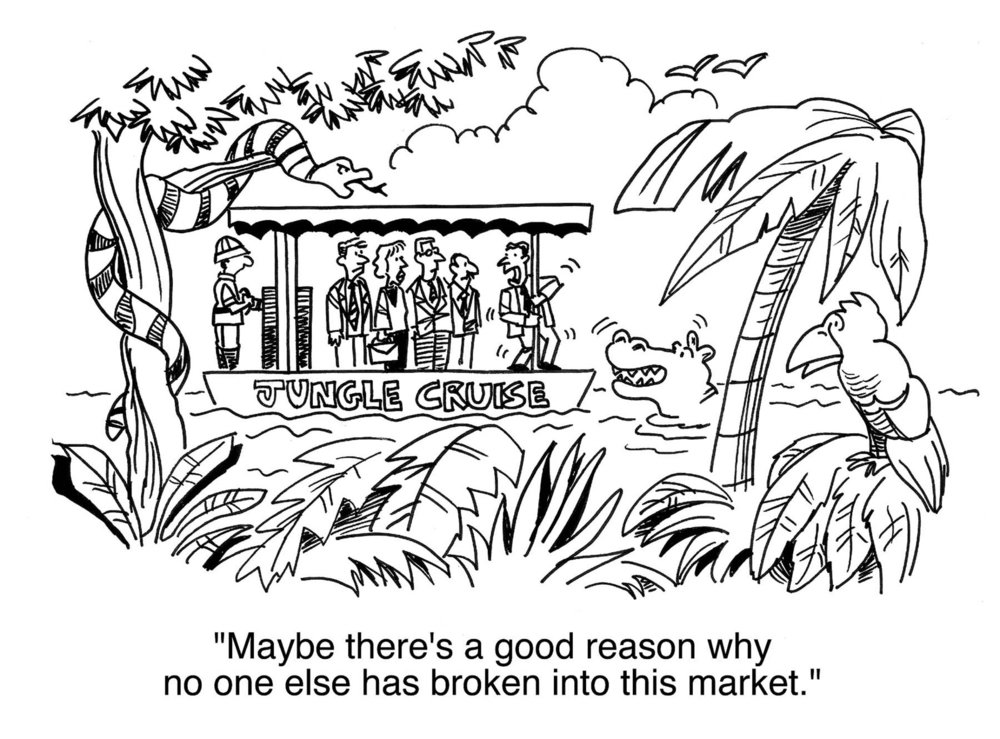

Our take

Wesfarmers’ adventure into the UK hardware market is unlikely to be the end of Australian corporates making poor foreign acquisitions. Management teams are incentivised to grow earnings, and acquisitions are presented as a quick way to achieve this goal. Atlas is very wary of companies announcing major offshore acquisitions as for every successful acquisition there seem to be several that end in tears. The common theme is one of excessively optimistic due diligence which underestimated the level of competition in the new foreign markets and the difficulty in managing diverse global businesses from a head office in Sydney or Melbourne.