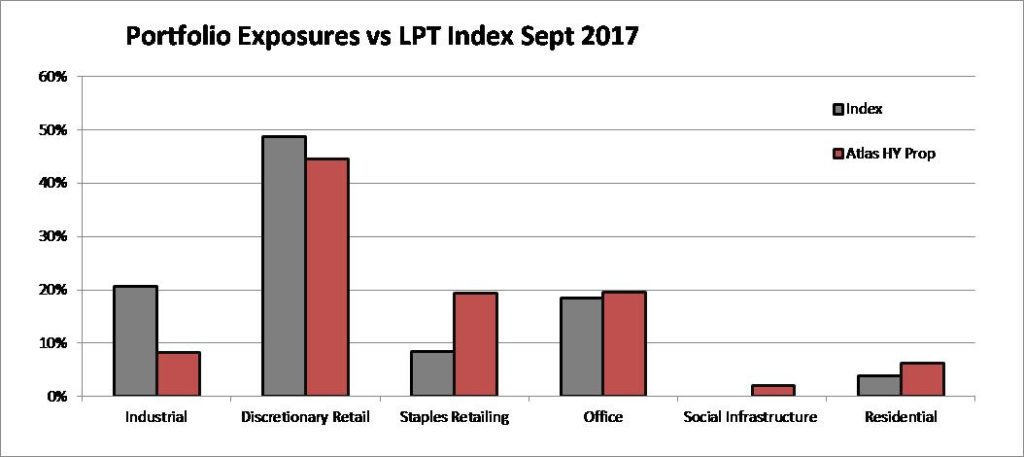

One of the misconceptions investors have is that the $123 billion dollar listed property index is primarily exposed to residential real estate. In fact, residential property comprises a small part of the index, with only 4% of the value of the index coming from trusts exposed to residential property. Further, this exposure primarily comes from developers selling finished apartments or home and land packages, not from actually owning housing real estate that is rented out.

Last month Mirvac announced they will be bringing Australia’s first major build-to-rent apartment development to market in a move that could potentially address housing affordability issues. In this week’s piece, we will look at why institutional investors have shied away from investing in residential developments, unlike in the US and the UK where this sector is a growing part of the Listed Property indices.

Residential property has attracted little interest from institutional investors as it is an area where retail investors have an investment edge. In the below chart, the grey bars show that exposure to residential real estate comprised 4% of the S&P/ASX 200 A-REIT index in September 2017, or $4.7 billion. This is dwarfed by the value of the discretionary retail ($59 billion), industrial ($25 billion), and office ($22 billion) real estate assets listed on the ASX. In comparison in the US, the residential sector accounts for around 25% of the $US2 trillion in institutional property investment, placing the sector just behind office.

Whilst the smaller transaction size of buying a two-bedroom apartment is attractive to retail investors (compared to an industrial warehouse or an office tower which may be valued in the tens to hundreds of millions), there are three structural reasons why retail investors dominate residential property investment.

Capital gains tax “crowds out” corporate investors

Although the domestic rental sector exists in LPTs in the US and Europe, in Australia the tax-free status of capital gains for owner-occupiers selling their primary dwelling has had the effect of bidding up the purchase prices of residential real estate. For example, when a company generates a $500,000 capital gain from selling an apartment, they would approximately be liable to pay approximately $108,000 in capital gains tax, whereas the owner-occupier pays no tax on the capital gains made on a similar investment. This discrepancy in the tax treatment allows the owner-occupier to pay more for the same real estate assets, and thus has contributed to the low yields mentioned below.

Negative gearing

Similarly, individual retail investors benefit from the generous tax treatment in Australia that allows them to negatively gear properties. There are three types of gearing depending on the income earned from an investment property: positive, neutral and negative. A property is negatively geared when the rental return is less than the interest repayments and outgoings, placing the investor in a position of losing income on an annual basis. However, under Australian tax law, investors can offset the cost of owning the property (including the interest paid on a loan) against other assessable income. This incentivises individual high-taxpaying investors to buy a property at a price where it is cash flow negative in order to maximise their near-term tax returns and bet on capital gains. Whilst companies and property trusts can also access taxation benefits from borrowing to buy real estate assets, a rich doctor on a top marginal tax rate of 47% has a stronger incentive to raise their paddle at an auction.

Yields on residential property too low

At current prices, the yield that residential property offers are not very attractive for listed vehicles. At the moment, the ASX 200 A-REIT index offers an average yield of 5%. This compares very favourably with the yields from investing in residential property. SQM Research reported recently that the implied gross rental yield for a 3-bedroom house in Sydney of 3% with a 2-bedroom apartment yielding 4% in July 2017. After borrowing costs, council rates, insurance, and maintenance capex, the net yield is estimated to average around 1%. With listed property investors focused on yield receiving on average ~ 5% from property trusts investing in office towers and shopping centres, such a low yield would only be accepted if it was offset by high and certain capital gains.

Mirvac’s new “build to rent” fund

In August Mirvac announced their intention to develop a build to rent fund with assets based initially in Sydney. This fund is likely to be targeted at institutional investor, rather than retail investors, who generally already have a significant exposure to residential real estate. This looks to be an opportunity for Mirvac to access both development profit (profit margin +25% in FY17) and also an ongoing funds management fee on the completed assets. However, we would be surprised to see much of Mirvac’s own capital invested in the fund. In 2017 Mirvac generated a 18% return on the $1.8 billion of capital invested in its residential development business (ROIC). Mathematically it is hard to see how investing in their own finished product will generate returns higher than the trust’s average cost of capital.

Our take

Whilst the residential sector is a large part of the overall stock of Australian real estate assets, without significant taxation concessions it is hard to see this sector garnering much interest from institutional investors, especially for income-focused investors such as Atlas Funds Management. The Atlas High Income Property Fund’s strategy of populating the portfolio with higher quality domestic rent collectors combined with a derivative overlay strategy to enhance income should continue outperform in a property market that is trading sideways. We see that the majority of returns over the next 12 months will come from distributions and income from writing call options over existing holdings, rather than spectacular capital gains.