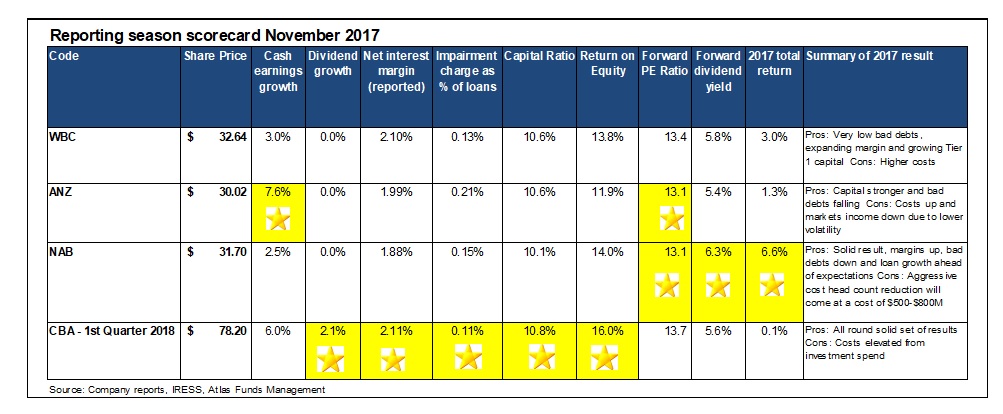

Over the last ten days the major Australian banks have reported their financial results for 2017, reporting collective annual profits of $31.5 billion. In comparison to the May reporting season (which saw the surprise introduction of a 0.06% levy on the liabilities and $50 billion being wiped off the bank’s collective market capitalisation), the results were mostly in line with expectations. A key feature that we noticed was how efficiently the financial impact of this “game changing” levy or tax was passed onto borrowers, something that we expected when we looked at the bank results earlier this year in the May Reporting Season Score Card.

In this piece, we are going to look at the common themes emerging from the November reporting season, differentiate between the different banks and hand out our reporting season awards to the financial intermediaries that grease the wheels of Australian capitalism.

In this piece, we are going to look at the common themes emerging from the November reporting season, differentiate between the different banks and hand out our reporting season awards to the financial intermediaries that grease the wheels of Australian capitalism.

Across the sector profit growth was generally in-line with the credit growth in the overall Australian economy. ANZ reported headline profit growth of 7.6% when backing out the impact of the sale of the bank’s Asian retail businesses, Esanda and property gains from 2016. The solid profit growth displayed across the sector was achieved by improving economic conditions and lower bad debts. All of the banks reported lower trading income due to decreased volatility over the year. During periods of higher market volatility, the banks can boost their income by both selling more foreign exchange and interest rate derivative contracts to their clients. However, they can also generate trading income by using their large balance sheet reserves to trade securities on the global markets.

Gold Star

Angry on costs: Reducing costs featured prominently in the plans of bank CEOs for the upcoming year, with much discussion about branch closures and headcount reductions. The removal of ATM bank charges and the migration of transactional banking from the physical bank branch to the internet is likely to deliver an efficiency dividend to the banks. NAB took the most aggressive stance, announcing that the bank will reduce its workforce by 6,000 employees due to business simplification and increasing automation. However, this will come at a cost with NAB expecting to book a restructuring charge of between $500-$800 million in 2018 and increases in investment spend by $1.5 billion.

Gold Star ![]()

Bad debt charges still very low: One of the key themes across the four major banks and indeed the biggest driver of earnings growth over the last few years has been the ongoing decline in bad debts. Falling bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay and that the outstanding loan amount is greater than the collateral eventually recovered. Bad debts fell further in 2017, as some previously stressed or non-performing loans were paid off or returned to making interest payments, primarily due to a buoyant East Coast property market and higher commodity prices. CBA gets the gold star with a very small impairment charge in 1st quarter 2018 courtesy of their higher weight to housing loans in their loan book. Historically home loans attract the lowest level of defaults.

Gold Star

Dividend growth stalled but may return: Across the sector dividend growth has essentially stopped, with CBA providing the only increase of 9 cents over 2016. With relatively benign profit growth a bank can either increase dividends to shareholders or retain profits to build capital (thereby protecting banks against financial shocks); but not both. In the recent set of results the banks have held dividends steady to boost their Tier 1 capital ratios. Additionally, dividend growth has been limited as the banks have had to absorb the impact of the additional shares issued in late 2015 to boost capital.

Looking ahead, there may be some capacity to increase dividends (especially from ANZ and CBA after asset sales), as the rebuild of bank capital to APRA’s standards is largely complete. The major Australian banks in aggregate are currently sitting on a grossed-up yield (including franking credits) of 8.2%.

Gold Star

Net interest margins in aggregate increased in 2017, despite the imposition of the major bank levy. This was attributed to lower funding costs and repricing of existing loans to higher rates. In response to regulator concerns about an over-heated residential property market and in particular the growth in interest-only loans to property investors; in 2017 the banks have repriced these loans higher than those repaying both principal and interest. For example, Westpac’s currently charges 6.3% on an interest only loan to an investor, which contrasts to the 4.4% being charged to owner occupiers paying both principal and interest. This has had the impact of boosting bank net interest margins.

One of the key things we looked at closely during this results season was signs of expanding net interest margin (Interest Received – Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets), and this was apparent even after allowing for May’s Major Bank Levy

Gold Star Australian banking oligopoly

Total Returns: In 2017 only NAB has been the top performing bank, benefiting from delivering cleaner results, after it jettisoned its UK issues with spin-off of the Clydesdale Bank and Yorkshire Bank. CBA has been the worst performing bank as it faces both the imminent retirement of its CEO and the uncertainty around possible fines from foreign regulators for not complying with anti-money laundering laws. This has resulted in CBA losing the market premium rating that it has enjoyed for a number of years over the other banks.

Gold Star

Our Take

What to do with the Australian banks is one of the major questions facing both institutional and retail investors alike. The Australian banks have been very successful over the past few years in generating record profits, benefiting from lower competition from non-bank lenders and record low bad debts. Looking ahead it is not easy to see how the banks can deliver earnings growth above the low single digits in an environment of low credit growth, increased regulatory scrutiny and the sale of some of their insurance and wealth management divisions.

Competition amongst the big four banks is likely to increase, as for the first time since 1987 (NAB’s purchase of Clydesdale Bank) we have no Australian banks distracted by foreign adventures, with all four focused on the Australian market. However, looking around the Australian market the banks look relatively cheap, are well capitalized and unlike other income stocks such as Telstra should have little difficulty in maintaining their high fully franked dividends.