Last month, Commonwealth Bank reported a record annual after-tax profit for the 2023 Financial Year of $10.1 billion. CBA’s profit result was viewed as controversial by some Corporate earnings’ obscene’ as CBA posts record profit, say Greens. However, this specious analysis ignores the fact that the “large” headline profit number must be divided by the 1.67 billion CBA shares on issue.

Whilst large corporations generate large profits in dollar terms, what is often ignored in much of the debate on corporate profitability is that these profits must be shared amongst millions of individual shareholders. In this piece, we are going to look at different measures of corporate profitability for large Australian listed companies, looking beyond the billion-dollar headline figure, which frequently does not tell investors how efficiently management is running the business or how well they are using the capital given to them. This piece originally was published in Livewire.

Different Measures of Profitability

As a fund manager, the $10.1 billion of cash profit generated by Commonwealth Bank over the past twelve months does not mean very much. Investors should be most concerned with the underlying earnings per share (EPS), which is what the owner of a single share of the company receives from the profit generated in a particular year. In CBA’s case, their cash earnings per share in the 2023 financial year compared with last year grew 5.9% to $6.06 – nice growth but not particularly exciting.

We also look at growth in EPS, as often, a company’s profits can grow substantially when it makes an acquisition. However, if that acquisition is funded by issuing a large number of additional shares, profit per share might not actually grow. This has been the case with fund manager Perpetual, which has increased net profit over the past five years from A$116 million to A$163 million in 2023. However, earnings per share have declined from $2.46 to $1.97, as the increase in profit was derived from acquisitions funded by dilutive equity issuances.

Conversely, a company’s profits may be down, but if this is due to the selling of a non-core division, it could be a good result for shareholders. In 2019, Suncorp sold its smash repairs and life insurance businesses, with the proceeds recycled into a share buy-back and a special dividend. Suncorp has increased annual earnings per share by +15% despite selling two businesses since 2019.

At a company level, we also look at measures such as returns and profit margins, which can be better measures of how efficient a company’s management team is at generating its annual profits. Furthermore, these measures allow the investor to compare companies in similar industries. For example, the profit margins of Coles and Woolworths or NAB and Westpac are compared on results day to evaluate how the different management teams are navigating the prevailing economic conditions.

Return on Capital Employed

Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) looks at the profit generated by the equity holders’ capital to establish the business and the debt that is taken on to support the business activities. ROCE is calculated by dividing a company’s profit before interest and taxes by the shareholders’ equity plus debt. The investment by shareholders includes both original share capital from the IPO plus retained earnings. Retained earnings are the profits the company keeps in excess of dividends paid and are used to fund capital expenditure to maintain or grow the company. Companies with high ROCE typically require little in the way of equity to keep the business running, little need to borrow from their bankers and are generally seen as good investments.

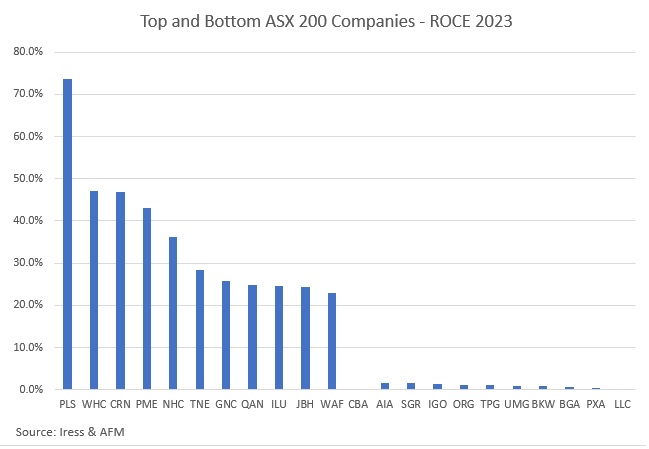

The above chart shows the top and bottom companies in the ASX as ranked by ROCE. The top ROCE earners include a lithium company (PLS), three coal companies (Whitehaven, Coronado and New Hope), a healthcare company (Promedicus), as well as cloud-based software provider (Technology One). Qantas appears high on this list for FY2023 as the net equity position of the airline is a mere $5 million due to accumulated losses, share buy-backs, and net debt of $2.9 billion. We would not expect Qantas to feature as highly in future years as the company spends between $12 and $15 billion to update its fleet after years of underinvestment in aircraft.

The common factor in these businesses is high commodity prices, low or no debt and minimal ongoing capital expenditure to run the company. The three coal companies are in an interesting position. Typically, high commodity prices result in takeovers and significant capital expenditure to expand existing mines, both of which result in higher levels of debt and equity issuance that expand a company’s capital base. Due to difficulties in getting approvals to expand mines and concerns about banks in the future refusing to lend to coal companies, management teams had paid down debt. This places the companies in a net cash position. Additionally, the companies have conducted on-market buy-backs to shrink their capital base. This results in high return on capital positions for the three coal miners.

Bringing up the rear is a range of capital-heavy businesses that require both large amounts of initial capital to start the business and regular capital expenditure to maintain the quality of their assets and finance their ongoing activities. For the purposes of this analysis, Atlas has only included companies that generated a profit in FY2023. This subset includes food companies (Bega and United Malt Group), a construction company (Lend Lease), a telco (TPG) and an embattled casino company (Star Entertainment).

Typically, when looking at this measure, miners, steelmakers, wineries and Qantas are prominently featured amongst the lowest returning businesses as they are operating in capital-hungry industries. However, in 2023, these three industries are currently enjoying cyclically strong earnings. Return on capital employed is a measure not used to evaluate banks due to the sheer size of total assets on the bank balance sheet used to generate profits – in CBA’s case, 2023, $1.25 trillion.

Profit margin

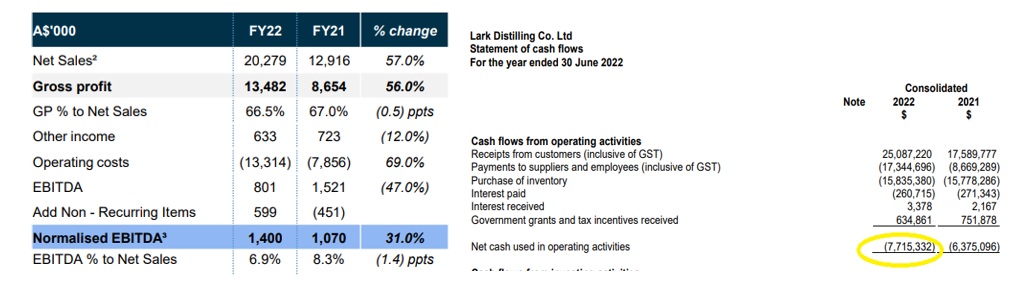

Profit margin is calculated by dividing net profits by revenues. It measures the percentage of each dollar a company receives that results in profit that can be paid to shareholders. Typically, low-margin businesses operate in highly competitive mature industries. The absolute profit margin is not always what investors should look at when analysing a company’s results, but rather a change in this margin. A rising profit margin may indicate a company enjoying operating leverage as profits are growing faster than costs. Conversely, a declining profit margin could indicate stress and might point to large future declines in profits.

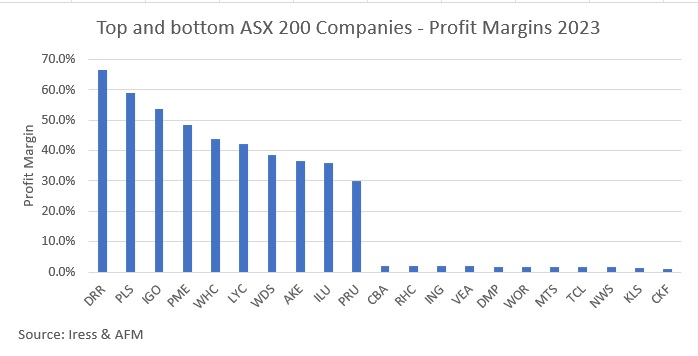

From the above chart that looks at the profit margins for ASX for the six months ending June 2023, the highest profit margins are generated by companies that are miners with operating mines enjoying high lithium and coal prices (PLS, IGO, Whitehaven and Lynas), royalty trust (Deterra), medical software (Pro Medicus) and energy company (Woodside).

Mining and energy companies enjoy high profit margins, as once the large offshore LNG trains or mines are built and operating smoothly, these assets have a low marginal cost of production per barrel of oil or tonne of ore. This metric does not account for the tens of billions in capital required to build these giant projects. The highest margin company on the ASX 200 is Deterra Royalty Trust, which is somewhat of an anomaly in that it does not actually operate an iron ore mine in the Pilbara but rather collects a quarterly royalty payment of 1.23% of the value of iron ore sold by BHP mined in its royalty area.

Low-profit margin companies characteristically receive large revenues but operate in intensely competitive industries such as grocery retailing (Metcash), fast food (Dominos Food, Collins Food) labour intensive healthcare and engineering (Ramsay Health, Worley), and petrol retailing (Viva Energy). Toll road operator Transurban made the list in 2023, making a minuscule profit despite toll roads being very profitable and high-margin businesses. Typically, the company’s $1 billion non-cash depreciation and the small $100 million annual maintenance capex charge allow Transurban to avoid making a statutory profit yet deliver healthy free cash flows to pay distributions to shareholders.

Generally, companies with low profit margins are obviously forced to concentrate closely on preventing their profit margins from slipping, as a small change in their margins is likely to impact the profit available for distribution to shareholders significantly.

Our take

While the banks and the large miners (BHP and RIO) generate large absolute profits, resulting in headlines around the billions of dollars they earn, they are generally not among the most profitable large listed Australian companies in terms of profit margins and returns on assets. Over the last six months, Commonwealth Bank’s 53,754 employees produced a $10.5 billion profit, representing a return on assets of 0.8% and a profit or net interest margin of only 2.07% on a loan book of $926 billion. When looking at companies to include in the Atlas Core Australian Equity Portfolio, the earnings power indicators are not the headline number but instead its return on capital, dividend and earnings per share growth as well as changes in profit margins.