Macquarie tips 10 per cent full-year profit growth

Macquarie Group posts a 5 per cent first-half profit growth to $1.3 billion and gives guidance of a 10 per cent growth for the full year.

Macquarie tips 10 per cent full-year profit growth

Macquarie Group posts a 5 per cent first-half profit growth to $1.3 billion and gives guidance of a 10 per cent growth for the full year.

by Mark Draper

Property trusts have been touted as a potential beneficiary from the Labor proposal to deny refunds from franking credits due to their relatively high level of unfranked income.

Professional property investors Hugh Dive, portfolio manager at Atlas Funds Management, and Adrian Harrington, head of funds management at Folkestone, offer some tips about what to look for when buying property trusts – whether listed or unlisted. Underlying these, of course, is the need to buy at a reasonable price. For the full article click on the below link.

What to look for when buying property trusts

From recurring earnings to debt structure, the experts outline what should be on your checklist before you buy.

We are generally pretty sceptical about new IPOs (initial public offerings). Occasionally, however, a great IPO comes along, either for a long-term investment or one with a high probability of making a short-term gain on its opening day, so it is always worthwhile to run the ruler over companies about to list on the ASX.

In this week’s piece we are going to look at the seven key questions we ask when assessing an IPO and apply them to Coronado Global Resources (ASX: CRN). Coronado’s prospectus was one of the largest that I have ever seen – close to 700 pages – perhaps reflecting what is likely to be the biggest IPO in 2018 with an expected market capitalisation of between $3-4 billion.

When analyzing IPOs few have been more eloquent on this subject that Benjamin Graham, the father of Value Investing.

“Our recommendation is that all investors should be wary of new issues – which usually mean, simply, that these should be subjected to careful examination and unusually severe tests before they are purchased. There are two reasons for this double caveat. The first is that new issues have special salesmanship behind them, which calls therefore for a special degree of sales resistance. The second is that most new issues are sold under ‘favorable market conditions’ – which means favorable for the sellers and consequently less favorable for the buyer” (The Intelligent Investor 1949 edition, p.80)

Coronado was founded in 2011 by private equity group EMG and since then they have spent US$1.2 billion acquiring 4 producing coal mines located in Queensland, and in Virginia and West Virginia in the US. This places Coronado as the 5th largest metallurgical coal producer globally with annual coal production of around 20 million tonnes (of which 75% is metallurgical coal and 25% thermal coal). In terms of profit, in 2017 60% came from the Curragh coal mine in Queensland and 34% from the Buchanan mine in Virginia.

Yes, as a miner Coronado essentially digs coal out of the ground and sells the coal predominately to steel mills in Northern Asia and the US. The thermal coal produced by Coronado is sold to the Stanwell power station in Queensland under a long-term contract.

Whilst coal is a dirty word globally – mainly in conjunction with power generation – 75% of Coronado production is metallurgical or coking coal, which is used in the smelting of iron ore to make steel. This is high-quality coal (commanding a higher price) that low is in ash, sulphur and phosphorous and will burn at a very high temperature (1,300C in a blast furnace). Metallurgical coal is necessary for the production of steel, both as a source of carbon and as a means of heating the iron ore to around 1,300C. By contrast, thermal coal can’t be used in steel production, due to both its high ash content and because it cannot be coked (a process to concentrate the carbon and reduce impurities by heating or cooking the met coal in an airless environment). Globally metallurgical coal is much scarcer that thermal coal and currently trades at twice the price of thermal coal per tonne.

Coronado digs the coal out of the ground at a cash cost of ~US$80/t (after royalties) and then sells it to steel mills in the US and Asia. Current prices per tonne of met coal are a little over US$200/t which makes this a profitable exercise. However, in Australia, Coronado’s product is priced at a discount between 6-16% to the benchmark price due to higher imperfections. Additionally, Coronado is subject to two separate royalty payments from production out of its two biggest mines which will cap profits in the near future. This results in Coronado having weaker profit margins than competitors such as BHP Coal and Whitehaven.

The biggest factors determining the price for metallurgical coal have been spikes in Chinese demand fueled by the construction of new Chinese mills (2006-2010) and pollution controls in China (2016-2018). During these periods Coronado’s coal mines have been very profitable, however, the below chart showing the metallurgical coal price over the past 10 years demonstrates that prices have been quite volatile. Over the past few years, metallurgical coal has risen from US$80/t in early 2016 to around US$200/t, leading to perceptions that the price is vulnerable to a fall if demand for steel weakens. Arguably current high prices above US$200/t for metallurgical coal encouraged Wesfarmers to sell the Curragh mine to Coronado earlier this year for A$700M (or at a multiple of only 1.5 times current annual profit).

The motivation behind the IPO is one of the first things to look at. Historically investors tend to do well where the IPO is a spin-off from a large company exiting a line of business, or when the vendors are using the proceeds to expand their business. Coronado is a little bit different from most IPOs – which typically see the vendors seeking to exit as much of their investment as possible – in that post the IPO 80% of the company will be retained by the vendors. This is an unusually high proportion to hold onto, as prospective investor usually likes to see the private equity owners retain a stake in the business on listing between 20-30%.

Whilst the owners floating a company may want to sell out completely, an effect of the 2009 Myer IPO – which saw the department store’s private equity owners sell their entire holding – is that new investors are unlikely to accept a full exit without a substantially lower price (in terms of profit multiples). However, seeing private equity owners retaining an ownership stake after the float is no guarantee that the IPO will be a sure-fire winner; the vendors of Dick Smith retained a 20% stake on the listing which was sold down 9 months later. Within three years of the float, Dick Smith went into administration.

The issue with an 80% stake being held by EMG is that the market will perceive this to be an overhang that may depress the CRN share price following listing. This 80% stake is subject to voluntary escrow. Coronado’s owners expect to raise around A$774 million. Of this around $600M will be used to repay debt and pay the costs of the IPO with the sellers banking around $110 million.

Yes: rising coal prices in 2017 saw Coronado’s net profit after tax move from -US$9 million loss to US$282 million profit in 2017 with a similar amount expected in 2018, before a big jump to US$400 million in 2019. However, this is very dependent on the coal price; for instance, a 10% change in the coal price would move 2019 EBITDA by either plus or minus US$200 million. The coal price is highly volatile, despite current very high prices, driven by expansion in the Chinese steel-making industry and demands for high-quality Australian coal over lower quality domestic Chinese coal to reduce pollution. During 2011-2016 the coal price fell dramatically, which saw Coronado’s US mines move to break-even at the EBITDA line (Earnings before interest tax depreciation and amortisation) and the glitzy Curragh mine’s EBITDA decline to US$61 million (2018 EBITDA $360 Million).

Coronado is expected to have net debt of only around 0.5x EBITDA in 2019, which will equate to an interesting cover of around 14x – two very strong debt metrics. This reflects a $500M reduction in debt as part of the IPO. However, we see that this is a business that cannot handle too much debt, due to the volatility in pricing of its product, of which Coronado is a price taker.

A decision to invest in Coronado should be based on your outlook for met coal prices. If current prices are maintained Coronado will trade on an EV/EBITDA multiple of around 4x, and based on the company’s stated pay-out ratio of 100% free cash flow this results in a dividend yield between 10-12%! Whilst this looks sensational, there are questions about its sustainability. Comparable coal stock Whitehaven Coal is currently trading on 5x EV/EBITDA multiple and a 6% yield with no debt. Globally coal companies are trading on an EV/EBITDA multiple of 4.5x, a very cheap multiple that indicates that the market does not believe that current high prices for coal will be sustained.

Using a conservative coal price of around US$150/t, our modelling indicates that Coronado’s free cash flow will drop from around $400M today to around $180M, which would place Coronado on a yield of 5%, i.e. solid but unspectacular.

Whilst we are comforted by vendor EMG retaining an 80% holding, we are concerned about buying into a recently put together company trading at peak earnings, especially when the previous owners of major assets that make up Coronado’s portfolio were happy to sell at lower prices.

We will be passing up Coronado due to this concern and our inability to predict the metallurgical coal price in the near future. Additionally, with the last line of Ben Graham’s quote from above on IPO’s in mind, given the movement in the coal price over the past few years, it is hard not to take the view that October 2018 may represent a very favourable time for Coronado’s owners to be selling shares to Australian investors.

Lendlease is similar to Goodman Group in that it has experienced internal development capability and strong capital partner relationships which help it build its other arm: funds management, where it earns fees on performance and management of billions of dollars worth of property. Growth in funds under management was 15 per cent to $30.1 billion in fiscal 2018. But how sustainable is that growth? And will all this be enough when the commercial property cycle changes? When interest rates rise and when property valuations and volume transactions fall away?

Lendlease is similar to Goodman Group in that it has experienced internal development capability and strong capital partner relationships which help it build its other arm: funds management, where it earns fees on performance and management of billions of dollars worth of property. Growth in funds under management was 15 per cent to $30.1 billion in fiscal 2018. But how sustainable is that growth? And will all this be enough when the commercial property cycle changes? When interest rates rise and when property valuations and volume transactions fall away?

Atlas fund manager Hugh Dive admits that Lendlease is a cyclical business but that it is shifting away from that.

“It’s a cyclical stock, but not as cyclical as it has been in the past,” he says. “If it had 40 per cent gearing you wouldn’t touch it!”

Lendlease’s net debt to total tangible assets, less cash is 8.2 per cent which will help the company wade through the cycles.

Dive also reminds investors that 40 per cent of Lendlease’s earnings come from offshore, giving it plenty of upside in the coming year from the depreciated Australia dollar.

To Read more:

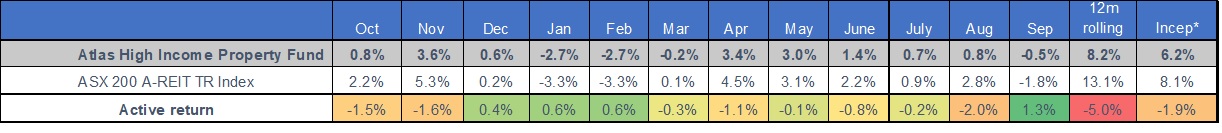

Go to Monthly Newsletters for a more detailed discussion of the listed property market and the fund’s strategy going into 2019.