Over the past few months, rising energy prices have dominated newspaper headlines, treating readers to the sight of politicians wringing their hands, promising to get to the bottom of this issue and find out who is responsible. Large power generators, energy retailers and transmission companies are accused of being behind the rising cost of lighting, heating and cooling our nation’s homes.

Whilst the profits that companies such as AGL Energy, Spark Infrastructure and to a lesser extent Origin Energy have increased over the past decade, we see that a significant proportion of the increase can be attributed to energy decisions made by various governments. As an economist, these price increases were predictable based on changes in the supply and demand curves of energy in Australia. There is scant evidence that they are the result of a long-term insidious plan by energy companies to capture a greater share of the nation ’s pay packets. In this week’s piece, we are going to look at energy prices impacting Australia’s consumers and industrial users alike.

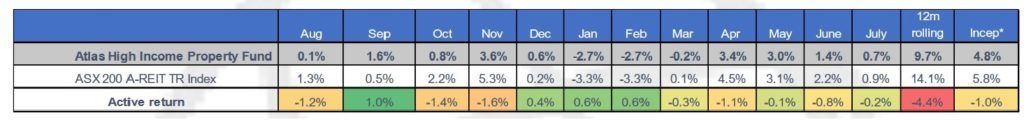

Energy prices this century

The above chart shows household gas and electricity prices in Australia and compares them to inflation. Using June 2000 as the baseline year, the CPI [Consumer price index which measures the prices paid by consumers for a basket of goods and services including energy] has risen by 61%. Over this same period, electricity has risen by +226% and natural gas by +207%. As you will note from the above chart, energy price rises roughly matched inflation up until 2008, however energy prices have accelerated in relation to CPI particularly since 2012. It is worth noting that electricity prices are influenced by natural gas prices in that gas is used in gas-fired power peaker plants that can be fired up in response to peak periods of electricity demand.

Gas Prices Up – a new source of demand

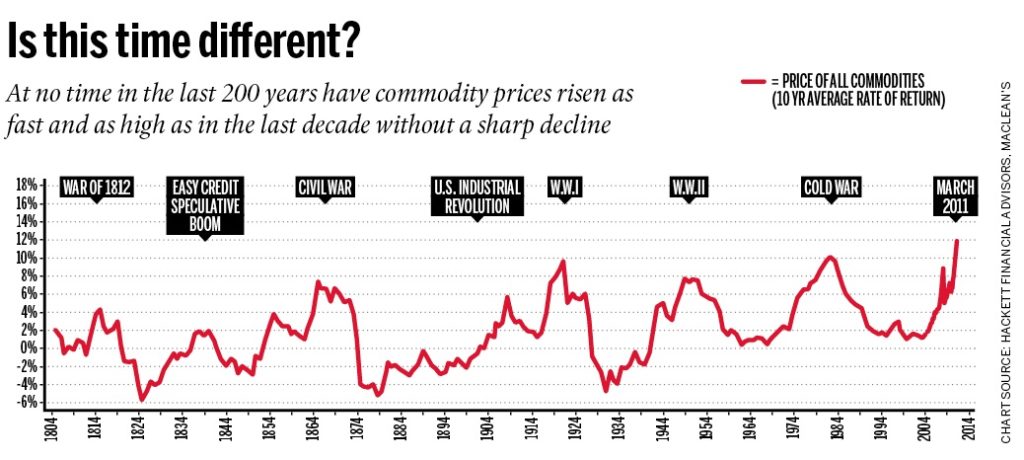

Due to the size of the Australian continent and the absence of pipelines linking the major fields off the coast of WA with Eastern Australia, gas prices are greatly influenced by geography. As you can observe from the below table, due to the lack of physical infrastructure WA’s gas from the giant offshore LNG fields is sold to consumers in Seoul and Tokyo rather than Sydney and Melbourne.

Until the construction of the construction of three liquefied natural gas (LNG where natural gas is cooled to -161 C to allow transportation) in the last five years, producers of natural gas on the East Coast of Australia could only sell their gas into the East Coast domestic market. This resulted in gas being priced below world prices for East Coast consumers. For example, in 2008 the wholesale price of 1 gigajoule of natural gas was $15 in WA versus $5 in NSW. The opening of these three export LNG plants in Gladstone in Queensland by Origin Energy, Santos and BG in 2015 and 2015 allowed the export of natural gas from Eastern Australia to Northern Asian customers that were willing to pay over $10 per gigajoule.

Additionally, unlike in WA which mandates that 15% of gas produced in the state is reserved for domestic consumers, no such gas reservation scheme was enacted on the East Coast of Australia. AGL’s plan to construct an LNG import terminal by 2020 to serve the Victorian gas market will further link the prices that Australian consumers pay for natural gas to the world market, with gas expected to be imported from the USA and Qatar.

Consequently, with a new source of demand for natural gas being introduced and East Coast gas markets opened up to world prices, domestic prices naturally gravitated towards the higher export price. The construction of these three LNG export terminals has not only had negative consequences for consumers but due to the elevated construction costs of around $71 billion have also been a burden for shareholders with returns below expectations.

Gas Prices Up – new sources of supply halted

At the same time that demand for natural gas was increasing, a range of decisions were made by governments in NSW and Victoria to restrict new supply. Arguing about the benefits and harms of coal seam gas is beyond the scope of this piece, but economics dictates that if demand is going up and supply is unchanged, prices will naturally rise. In 2012 Victoria imposed a moratorium on coal seam gas exploration and in 2015 the NSW government banned new gas exploration. This saw AGL announce that it would not proceed with their projects in NSW and that they would be relinquishing their exploration licences. This action contributed to the energy company recording an impairment charge of $640 million in 2016. We note that in April 2018 the Northern Territory reversed its ban on gas exploration outside towns and conservation areas in a move designed to put downward pressure on power bills.

Generation Costs Up – changing the mix and reducing supply

In the electricity market prices have been driven higher by the Federal Government’s Renewable Energy Target. This will require electricity retailers to acquire a fixed proportion of their electricity from renewable sources and is likely to result in 33,000 GWh of Australia’s electricity coming from renewable sources by 2020. Politicians seem surprised that regulations have added to electricity costs, following the closure of coal-fired base-load power stations in favour of more expensive renewables. For example, in 2017 Energie closed the Hazelwood power station that had previously supplied up to a quarter of Victoria’s electricity and AGL have announced that they will be closing the 1,680-megawatt Liddell coal-fired plant in 2022. Whilst we recognise that burning coal to generate electricity releases carbon into the atmosphere contributing to global warming, it is also a very cheap and consistent method of generating electricity. Additionally, coal-fired power plants are well-placed to provide a base-load of consistent generation, as these plans can generate electricity continuously, without requiring the wind to blow or the sun to shine.

Until the battery storage technology catches up to allow generators to store significant amounts of electricity, relying on solar and wind power generation requires natural gas-fired generation to step in to maintain consistent supply. As discussed above, this source of electricity generation is more expensive today that it was 10 years ago. Switching power generation to renewables – whilst socially desirable – comes at a cost, and this is reflected in higher energy bills. Further, in any market when supply is removed and demand remains relatively constant, prices tend to rise. This effect has proven profitable for incumbents who have generators, such as AGL Energy.

Our Take

Rising energy costs have impacted consumers and industrial users alike, but they have not arisen in a policy vacuum nor as part of a conspiracy. We see that they are the logical outcome of decisions that have changed the supply and demand for energy and that various companies have predicably acted to generate profit from these shifts. In the Atlas equity portfolio, we own positions in AGL Energy and Spark Infrastructure, both of which have benefited from changes in the energy markets in Australia over the past ten years. Neither of these companies is involved in the LNG export terminals that at this stage look to be a poor investment for shareholders.