Category: Uncategorized

Bank Reporting Season Scorecard

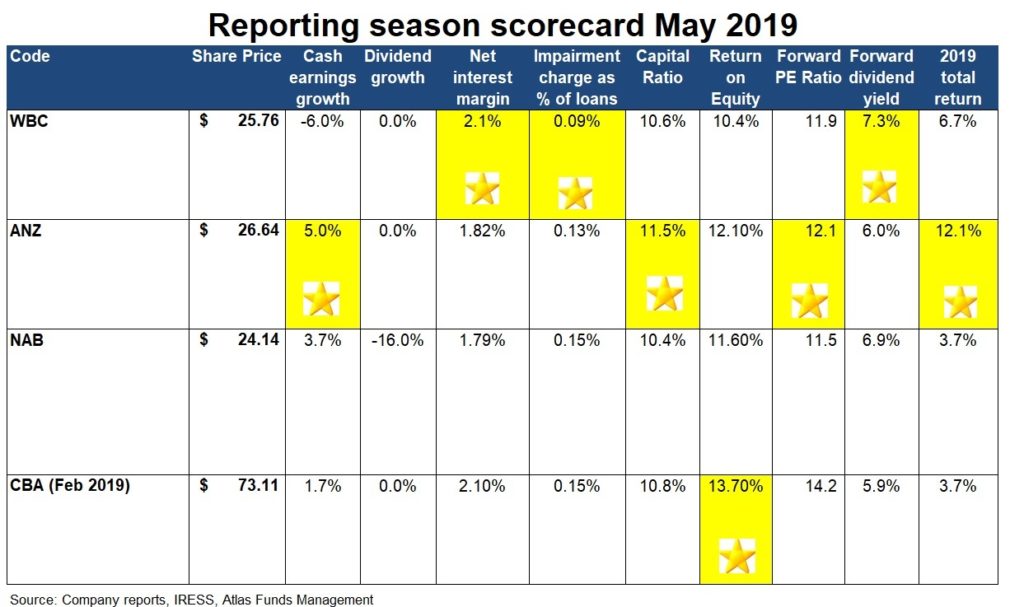

On Monday Commonwealth Bank released their quarterly results. This concluded the May banks reporting season in which NAB, ANZ and Westpac revealed their profits for the six months ending March 2019. The revelations of the Royal Commission on Financial Services have resulted in extensive remediation provisions, increased compliance costs and a spike in legal fees, at a time where credit growth has slowed dramatically. This unusual set of circumstances has generated a complicated set of financial results to analyse; a task made harder still by Commonwealth, ANZ and Westpac all divesting divisions.

In this week’s piece, we are going to look at the themes that can be gleaned from the approximately 800 pages of financial results released over the past 14 days by the financial institutions that grease the wheels of the Australian capitalism and award gold stars based on performance over the past six months.

Remediation

Customer remediation was a key theme for the results in 2019, with banks

compensating customers or taking provisions related to financial advice,

banking, insurance and consumer credit. Australia’s banks have taken

remediation provisions over the past 12 months of between $900M (ANZ) and $1.4b

(Westpac), with NAB and Commonwealth around the $1.1b mark. ANZ’s lower level

of provisioning does not reflect any lack of prudence, but rather its

historically low level of exposure to financial advice and funds

management.

No

star is given. The fact that the banks have made these provisions is bad for

both customers and shareholders.

Profit growth?

Across the banking

Gold Star

Dividends

Unsurprisingly given the level of remediation provisions and political scrutiny, no bank grew their dividend per share in 2019, though NAB did cut theirs by 16 cents to $0.83. This cut did not spark much of a reaction from the market as NAB had been paying out close to 100% of cash earnings after remediation charges in 2018. This was unsustainable as a bank needs to retain some earnings to grow their capital base and thus, their ability to lend to customers. Westpac maintained their dividend, but introduced a 1.5% discount on their dividend reinvestment plan, a move designed to raise capital. Interestingly, Westpac also brought forward its interim dividend payment date by nine days to June 24 2019. This move gives Westpac’s investors three dividends in the 2019 financial year, with payments in July 2018 and December 2018 as well as this one in June 2019. Atlas interpret this as a move to designed to beat Labor’s changes to franking credits.

Gold Star

Bad

debts

One of the biggest drivers of earnings growth over the last few years has been the ongoing decline in bad debts. Falling bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay and that the outstanding loan amount is greater than the collateral eventually recovered. Bad debts remained low in 2019, with the housing banks Westpac and Commonwealth reporting the lowest level of bad debts despite a cooling in the East Coast property market.

Furthermore, at the big end of town, there were no major corporate collapses over the past six months, keeping corporate bad debts low. ANZ, NAB and Commonwealth reported a marginal increase in bad debts, albeit at levels that are around half of the long-term average (excluding 1991) of 0.3% of gross loans and acceptances. Westpac reported unusually low bad debts at a mere 0.09% of loans, though this low bad debt charge was boosted by a release of provisions previously taken on loans made by their business bank.

Gold Star

Keeping it simple

The main new theme to emerge from this reporting season was that banks are

looking to reduce their footprint on the Australian financial services

landscape by divesting businesses that are deemed to be non-core or are in

areas that have the potential to damage the reputation of the bank’s core

lending business. Over the last year, Commonwealth Bank has sold their

insurance and funds management business, ANZ Bank has sold their wealth

business to IOOF – though this may come back due to ongoing issues at IOOF –

and in March Westpac announced that they are exiting personal financial advice.

NAB also announced plans to sell MLC wealth management by 2019.

These moves can be seen as acknowledging that the costly exercise of creating

vertically integrated financial supermarkets was a mistake. While some of the

moves to sell these carefully constructed divisions may be attributed to the

events of the Royal Commission, some of the sales were consummated well before

the titans of Australian finance faced the harsh light of the witness stand.

No Star Given –

ultimately a flawed strategy

Interest Margins

The banks’ net interest margins [(Interest Received – Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] in aggregate decreased slightly in 2019. The decrease was attributed to increased competition and customer remediation charges. However, these pressures were offset by pricing mortgages upwards and, as many retirees will be aware, reducing the interest rate being paid on deposits. Looking forward, the bank’s interest margins are likely to be fairly healthy as their funding costs have continued to decline over 2019. Funding cost refers to the overall interest rate paid by the banks to source the funds that are used for short-term and long-term loans to their borrowers. Westpac reported the highest net interest rate margin in May 2019, which reflects both their greater focus on mortgages (which attract a higher margin than business loans) and the impact of higher pricing on those loans.

Gold Star

New

Zealand

Late in 2018, the RBNZ released a consultation paper on bank capital requirements, essentially saying that they would like the banks that lend to New Zealanders maintain a Tier 1 Capital level of 16%, with a decision to be made in September 2019. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA)’s standard is 10.5%. New Zealand is a strange market globally as it is both a significant capital importer and also 88% of its lending comes from foreign-domiciled banks (mainly the Big 4 Australian banks).

The RBNZ consultation paper is based on the naïve assumption that the banks would do nothing in response to this additional capital requirements, and that Australian shareholders would blithely fund New Zealand’s aspirations to be the best-capitalised banking system in the world. Under current NZ mortgage prices and assuming higher capital requirements, the banks would be writing mortgages in New Zealand giving returns below their cost of equity: an untenable position.

If implemented this would require each of the Big 4 Australian banks to move ~ $3B in capital to New Zealand. ANZ, as the biggest bank in NZ, would need the greatest amount, but it is also the bank with the largest excess capital position post asset sales in 2017. ANZ’s management said that if these capital controls were implemented, the bank would likely ration credit going into NZ and reprice NZ loans upwards to account for the higher capital charge. On Friday afternoon ANZ share price was impacted as the RBNZ hit back questioning the capital models ANZ is using in New Zealand.

Our take

How to approach investing in Australian banks is one

of the major questions facing both institutional and retail investors alike. We

expect the banks to deliver around 3-5% earnings growth as they face low credit

growth, increased regulatory scrutiny, and the sale of some of their insurance

and wealth management divisions, though there are significant cost-out

opportunities from rationalising their 1,000 branch networks around Australia.

However, if investors

examine the wider Australian market the banks look relatively cheap, are well

capitalised, and – unlike other income stocks such as Telstra – should have

little difficulty in maintaining their high fully franked dividends.

Additionally, their share prices are likely to see support over the next 12 months

as the issues raised in the Royal Commission are addressed. Additionally,

Commonwealth Bank and ANZ are likely to offer share buybacks, as the proceeds

from the sales of non-core assets come through.

How do lower interest rates impact the way analysts value shares, or company valuations?

Interest rates have been steadily declining over the past decade and have had an impact of asset values world-wide. In this week’s TT we are going to look at the impact of falling interest rates on share prices with Hugh Dive from Atlas Funds Management.

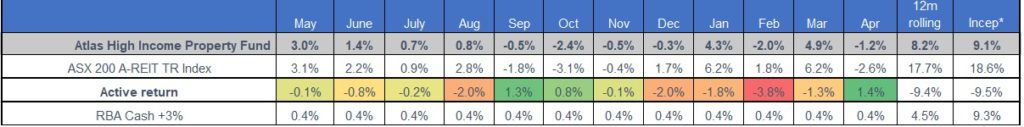

April Monthly Newsletter Atlas High Income Property Fund

- The S&P/ASX 200 A-REIT index had a weak month in April falling by -2.6%, the sector’s first fall since November 2018. Given the Listed Propery sector’s very strong performance in 2019 it is not surprising to see the sector take a step back.

- The Atlas High Income Property Fund declined by -1.2% in April with weakness in domestic retail landlords being offset by gains in Unibal-Rodamco-Westfield. In weak markets such as we saw this month; the Fund’s risk management strategies acted in-line with expectations and reduced volatility.

Go to Monthly Newsletters for a more detailed discussion of the listed property market and the fund’s strategy going into 2019.

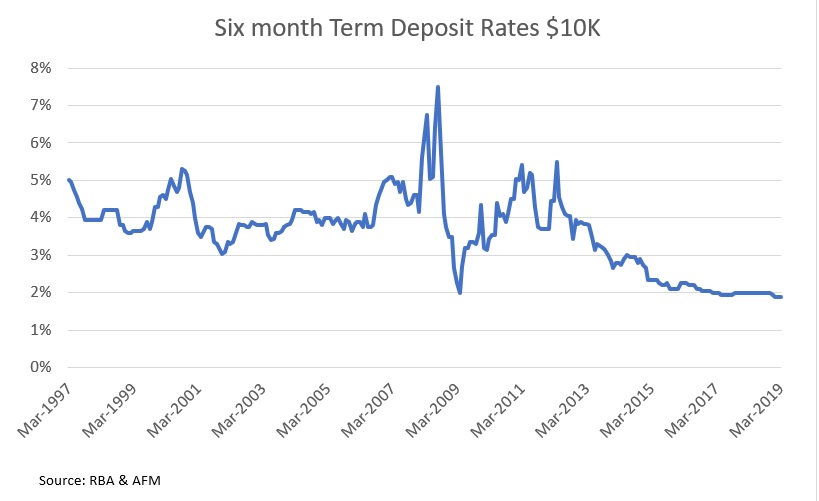

Financial Repression and Falling interest rates

In 2019 we have seen the Australian 10-year bond rate fall from 2.75% to 1.75%, a significant move given that in April 2018, the market was expecting that interest rates would be rising throughout 2019 and 2020. While this sounds a bit esoteric, falling bond rates depresses term deposit rates. At the moment the market expects that the RBA will cut the cash rate later on in the year (currently at 1.5%), possibly at their meeting on Melbourne Cup Day in November.

Further cuts to the interest rate will only intensify the hunt for yield among investors, especially those in pension phase looking to live off the income delivered by their investments. As term deposits roll off and investors are faced with pretty meagre reinvestment options, we would expect investors to rotate investments out of cash and into other yield assets such as shares and listed property trusts. In this week’s

Financial Repression

Financial repression is a term used to describe measures used by governments to boost taxation income, economic activity and demand for government debt. These measures include attempts to hold down interest rates to below inflation and represent a tax on savers, conferring a benefit on borrowers. The positive impact of these measures is that it becomes cheaper to borrow money to invest possibly boosting economic growth, however this effectively becomes subsidised by the nation’s savers.

Over the last

While the 2% rate on one-year term deposits in Australia looks grim (especially in light of inflation running at 2%), spare a thought for investors in other major Western nations. Retirees in the USA are currently being offered 0.03% from Bank of America, in Germany a touch higher at 0.05% with HSBC in the UK offering 0.55% all for the same six-month term deposit. Near zero rates in Europe, Japan and the US (and historically low rates in Australia) are positive for middle-aged borrowers, asset owners and corporates refinancing debt at lower rates; but represent a significant negative cost for savers.

Stable and Growing Distributions

When we look at dividend-paying stocks and high-yielding listed property trusts we are not overly concerned with the trailing or next period payment, but rather in understanding whether a company can maintain their distribution over the long term and importantly grow it ahead of inflation. Indeed, picking a basket of stocks or trusts solely based on their historical dividend yield has been a path to under-performance. When looking through the list of the highest yielding securities in the ASX200, a common factor is usually a high payout ratio (dividend per share divided by earnings per share).

Payout Ratios too high

Companies with a high payout ratio generally possess fewer options to grow a distribution or maintain it over a variety of market conditions. High payout ratios are often attributed to companies that are either mature or in operate in low-growth industries with few investment opportunities to grow their business, or management looking to maintain the dividend in an environment where the company’s earnings are deteriorating and thus prop up the share price. In some situations, these companies are even borrowing to pay their dividend may be retaining insufficient cash to maintain their assets. This was the case with Telstra for several years, until they bit the bullet and cut their dividend from 28 cents per share to 22 cents per share in 2018.

Looking at other well-owned high yielding stocks on the ASX, it is tough to see NAB maintaining their dividend in the future. In 2018, NAB paid a dividend of $1.98 on cash earnings of $2.02 per share, given NAB has just taken on a new CEO and need to build their capital position by retaining earnings, we would be very surprised if the bank does not cut their dividend later on in 2019.

Maintaining asset quality for property trusts

When assessing the quality and sustainability of the distribution of a property trust you have to look at the percentage of the distribution covered by earnings less the costs of maintaining the quality of the trust’s assets such as replacing lifts, escalators and indeed incentive payments necessary to retain tenants. Before the GFC a large number of property trusts were paying out virtually all of the rental income they collected and were not retaining sufficient funds to cover maintain the quality of their assets. Trusts with higher distributions saw their share prices re-rated higher. In the short term these capital improvements were covered by borrowing money and issuing new equity, but eventually these high distributions proved to be unsustainable and were cut.

Franked dividends = tax payments

Franked dividends have a tax credit attached to them which represents the amount of tax the company has already paid on behalf of their shareholders for the profit they have earned in any given year. While companies can make a range of aggressive accounting choices that can boost their earnings per share (and dividend per share), a company is extremely unlikely to maximise the tax that they pay to the government.

Firms that pay franked dividends have significantly more persistent earnings than firms that pay unfranked dividends, as it indicates that a company is building up tax credits by generating taxable earnings in Australia.

A great example of the role that franking plays in indicating the sustainability of a dividend occurred in 2014 where steel company Arrium paid unfranked dividends in 2013 and 2014. Despite paying dividends and reassuring the market as to the company’s future, Arrium conducted a massive capital raising in late 2014 to shore up a shaky balance sheet and ultimately went into administration in 2016 with debts of $4 billion. Here the lack of franking could be viewed as an indicator that the quality and sustainability of the company’s dividends was not high. However, this measure is not useful for companies such as CSL and Amcor who generate large proportions of their profits outside Australia are unable to pay fully franked earnings.

Our View

When constructing a portfolio designed to deliver income above the meagre returns being offered by term deposits, Atlas see that it is not enough simply to pick high yielding securities. In selecting yield stocks investors should make a detailed assessment of the ability of a company to continue paying and growing distributions ahead of inflation.

Demographic change will see more investors are moving from the accumulation to the retirement phase, which will increase demand for equity fund managers to deliver income to investors. This could be very interesting as in the fund’s management world, the vast majority of the focus is on growing capital by buying stocks that the fund manager believes will rise dramatically. This growth approach typically results in swings in the value of portfolios and minimal dividends. Alternatively an “income approach” to investing involves thinking about how an investor’s capital can be deployed to deliver ongoing income necessary to fund a comfortable retirement.