Blue Chip stocks are the large well-established household names, in the top 50 companies listed on the ASX with a market value in the tens of billions. Stockbrokers recommend these companies to their clients based on the perception that they are safe and stable and following the axiom “Nobody ever got fired for choosing IBM“. They are viewed safe for advisors to recommend even if they fall in value. However, like Ozymandias in the poem by Shelley, strong and financially sound companies are not always permanent and can become buried in the Egyptian desert like the statue of the pharaoh.

“I met a traveller from an antique land, who said— “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, the hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear: My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Shelley’s Ozymandias 1818

In this week’s piece, we are going to look at blue chips on the ASX over the last quarter century, the factors that caused them to decline and some thoughts on the current crop of “blue chip” companies on the ASX and their permanence.

What is a blue-chip stock?

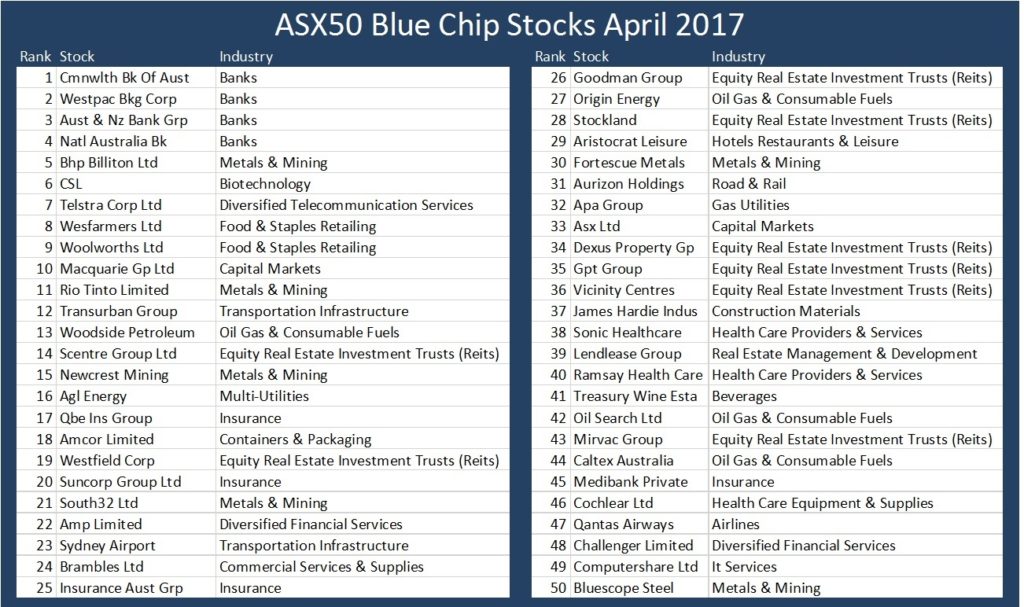

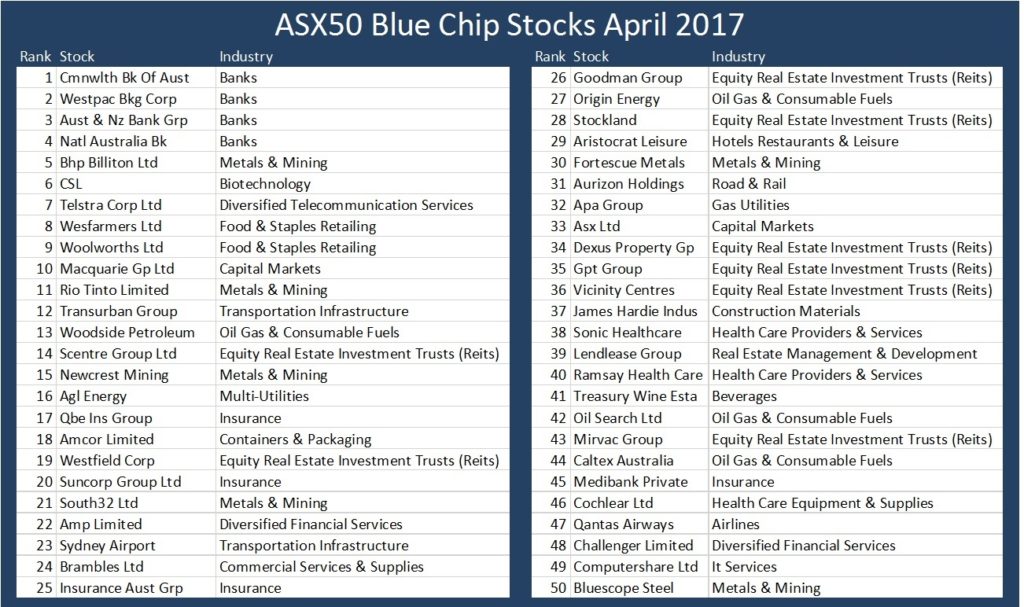

The term “Blue Chip Stock” was first used by Oliver Gingold of Dow Jones in 1923 and referred to high priced stocks. “Blue” was a poker reference, as in poker sets the highest value chip is traditionally the blue one. Since then the term has come to denote high quality stocks, with consistent revenue growth and dominant market positions in their industry. They typically have a stable debt to equity/interest coverage ratios and generate superior return on equity (ROE). Over time this translates into a high market capitalisation that places a company in the Top 50 companies listed on the ASX. Currently the smallest stock (BlueScope Steel) in the ASX Top 50 has a market value of almost A$7 billion.

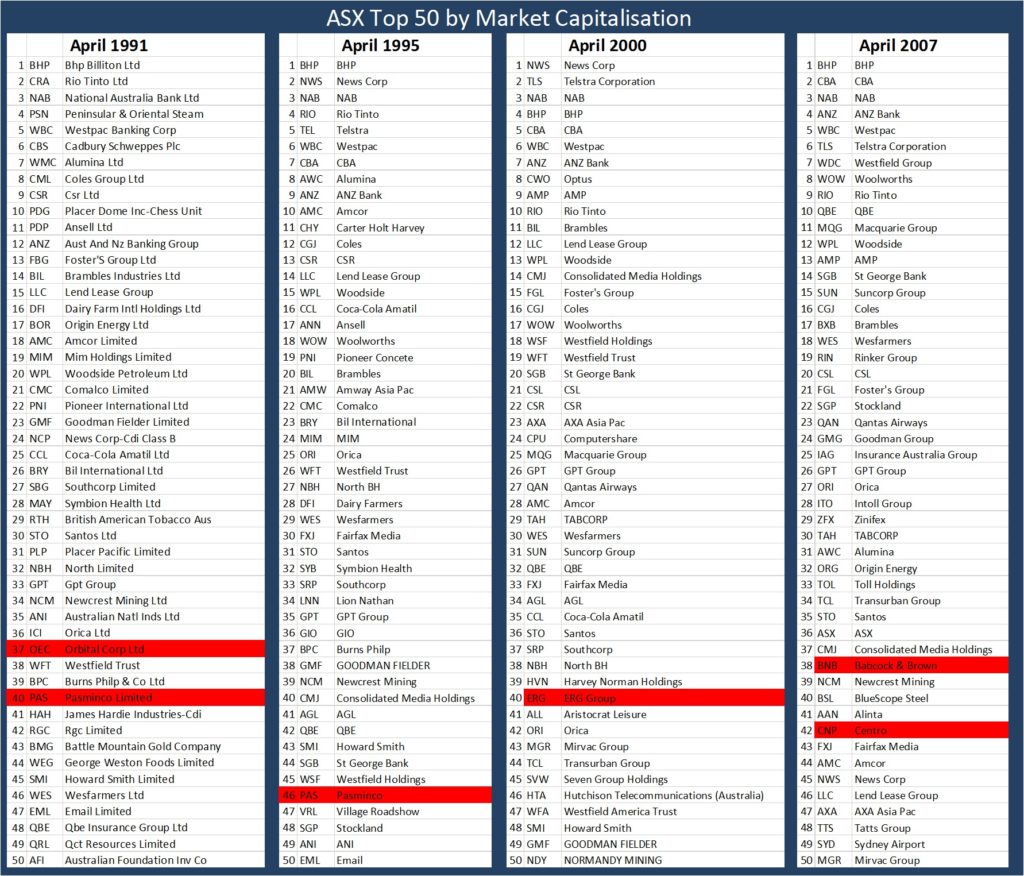

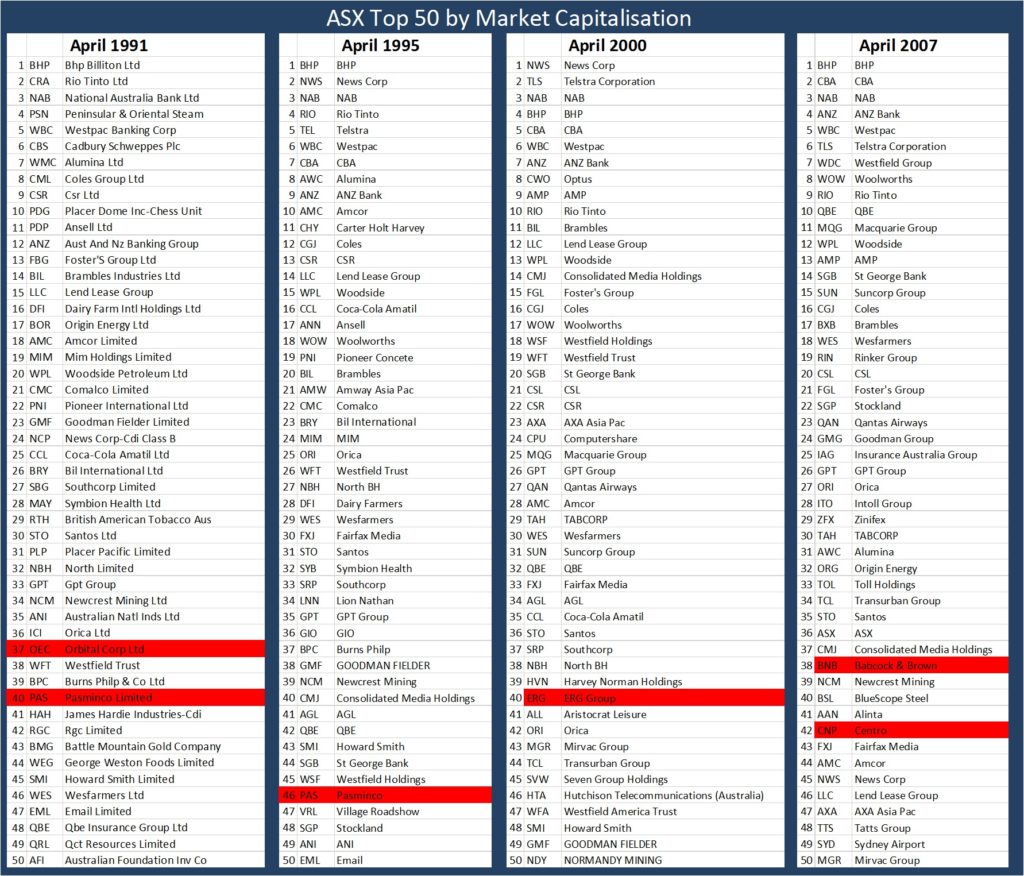

The below table looks at the Top 50 stocks on the ASX by market valuation in four points in time over the last 26 years. There are many familiar names such as BHP and Westpac that were considered blue chips in 1991 and retain that status today, but there are also many that would be unfamiliar to many investors today. Whilst most of these (Cadbury Schweppes, North Broken Hill, PNO, Dairy Farm Holdings) have disappeared from the share market due to being taken over by other companies, in each period there are a number of supposed blue chips that ultimately went into administration or faded away to a small fraction of their previous size. The faded blue chips in the table are coloured in red. We will now examine the factors that contributed to their declines.

Too much debt

In early 2007 shopping centre trust Centro Properties was riding high after making a string of acquisitions in Australia and the USA. It was viewed as highly innovative, dubbed the Macquarie Bank of Property Trusts due to its use of debt to create a global property empire. After acquiring a portfolio of 469 small shopping centres across 38 US states for A$3.9 billion, the trust was managing A$26 billion of property. As a result of the acquisition, Centro Properties upgraded its forecast 2008 financial year distribution growth to 19%. However instead of rising distributions, in December 2007 Centro Properties faced significant problems in refinancing US$5.5 billion of debt that was due in a very challenging market. Additionally, the shopping centre owner faced questions about the accuracy of their financial accounts after billions of dollars in short-term bridging debt was classified as long-term debt. As a result of asset write offs, Centro Properties in June 2009 reported a negative net tangible assets (NTA) of -$2.23 per share (it was trading at $0.16 per share at the time). Ultimately equity holders were essentially wiped out as the mountainous debt burden was converted into equity.

Financial Engineering

In 1998 zinc miner Pasminco was one of the premier global zinc miners after buying the Century project from Rio Tinto. The company developed an audacious hedging strategy to lower debt costs by borrowing in USD and hedged the currency based on the expectation that the AUD would remain between US68c and US65c. Unfortunately, the AUD/USD fell to below 51c in 2001 at the same time that the zinc price crashed. This left the company with limited cash flow and losses on the hedge book that blew out to $850 million when the company went into administration in late 2001.

The combination of too much debt and financial engineering

No discussion of faded blue chips would be complete without looking at investment bank Babcock & Brown. At its peak in June 2007, the investment bank was lauded as a creative user of financial structuring and a fee-generating machine that propelled the company’s share price to $34.63, with a market capitalisation above $9 billion. From meetings that I had with Babcock & Brown management prior to the GFC, they also made no secret of the fact that only a small amount of their earnings could be characterised as “recurring” and that most of the profit (used to pay dividends) was generated by revaluing assets cannily acquired by the company.

Similarly, to Centro, Babcock & Brown both entered the GFC with too much debt and – more importantly – too much short-term debt that needed to be refinanced in a challenging market. In June 2007, the Babcock & Brown group had amassed $80 billion in assets, supported by $77 billion in debt, much of this held off balance sheet or characterised as “non-recourse” and held by satellite funds. The company collapsed in 2009 after a falling share price triggered debt covenants and the company was unable to refinance the debt due. Ultimately, in very complex liquidation proceedings the noteholders ended up receiving 2c in dollar for bonds held, with equity holders receiving nothing.

Technology that did not work as expected

The orbital engine was invented by Ralph Sarich in 1972and at one time was expected to revolutionise combustion engines, with fewer moving parts and greater efficiency. In 1991, the future for Orbital – a company that owned the technology for orbital engines – looked bright and BHP took a 25% stake in the company. Despite this promise, a range of technical problems with cooling and lubricating the engine proved unsolvable and both the founder and BHP ran for the exits. Orbital still exists selling fuel injection technology and propulsion systems for drones, but with a share price of $0.59 which is a long way from its peak at $24.

ERG’s future looked bright 17 years ago and was a glamour tech stock listed on the ASX offering smartcards for mass transit systems from Moscow to Manila. Whilst the technology itself was sound the company was effectively sunk, not by the offshore moves but by difficulties in implementing the ERG’s T-Card in Sydney and issues with the NSW State Government which led to the project being scrapped. Ultimately this resulted in lawsuits and the company was delisted in 2009.

The above table shows the ASX Top 50 as of April 2017 ranked by market capitalisation. Whilst it is usually hard to identify at the time which strong companies will falter in the future, history strongly suggests that amongst this list there are one or two companies, currently considered blue chips that will either go into administration or slide back into insignificance. Below we identify some considerations that might influence the future fates of current blue chips.

High Debt

In 2013 Fortescue looked like a candidate for a blue chip that might blow up, with 70% gearing resulting from $10.5 billion in net debt. However, a period of sustained high iron ore prices has allowed the company to pay off $6.5 billion in debt and reduce gearing to a more manageable 30%.

Amongst the blue-chip stocks in the table above, the companies with the highest debt burden as measured by gearing (net debt divided by total equity) are Sydney Airport (770%), APA Group (242%), Transurban (225%) and Ramsay Healthcare (135%). The key characteristic of these heavily geared companies is the view that the stable returns from airports, pipelines, toll roads and hospital procedures affords the ability to service high levels of debt.

Whilst these companies own wonderful assets and point to both the spread of debt maturities and their interest rate hedges (which lock in a portion of the company’s debt at a fixed rate), these hedges will expire and debt currently attracting low rates will almost certainly have to be refinanced at higher rates. For example, in the five-year period 2020 to 2024, Sydney Airport will have to refinance on average $806 million in debt per year.

Technology does not work as expected

Whilst we do not consider this likely and believe that the company has instituted many safeguards, blood therapy company CSL does face the risk of product recalls through contamination. In 2008, CSL’s rival Baxter faced a product recall after 81 deaths were linked to tainted blood thinning drugs produced under contract in China, but sold in the US under Baxter’s name.

Left Field

Political factors could potentially derail BHP spin-off S32, which has climbed into the ASX Top 50 courtesy of higher coal and manganese prices. In February S32 reported that 35% of their profits were earned from the company’s coal and manganese mines and aluminium smelters in South Africa and Mozambique. Significant political unrest, power disruption from Eskom or amendments to South Africa’s 2002 mining charter requiring higher percentages of black ownership could result in significant falls in S32’s share price.

Our Take

We see that investors spend far too much time trying to pick the next Apple or CSL and not enough time thinking about whether there is a Pasminco lurking in their portfolio. Rather than chasing high return and higher risk investments, Atlas observes that superior performance and lower volatility of returns are best delivered by concentrating on avoiding mistakes or “performance torpedoes”. Looking at the current list of blue chip stocks, we consider that the most probable candidate to become a fallen angel is likely to come from the list of highly geared utilities.

Insiders and insider trading

Insiders and insider trading