The last few months have been tough for shareholders in the major Australian financial services companies, who have seen their share prices drift lower throughout March and April. Evidence of misconduct presented at the Royal Commission on Financial Services has fed market fears that bank profitability will be diminished in the future. However, over the past ten days, the major banks have reported their profit results for the past six months, showing the market how their underlying businesses are performing and how the management teams plan to address the issues raised at the Royal Commission.

In this piece, we are going to look at the common themes emerging from the banks in the May reporting season. We will differentiate between the different banks and hand out our reporting season awards to the financial intermediaries that grease the wheels of Australian capitalism.

Simplification

Simplification

The main new theme to emerge from this reporting season was that banks are looking to reduce their footprint on the Australian financial services landscape, by divesting businesses that are deemed to be non-core. This results season was characterised by complexity arising from either announcements of new significant moves, or that were complicated by sales made in 2017.

In May Commonwealth Bank announced plans to spin off their wealth management business Colonial First State, which followed the sale of the life insurance business in 2017. ANZ’s result was complicated by the sale of both their wealth management and life insurance businesses in 2017. NAB also announced plans to sell MLC wealth management by 2019. Additionally, Westpac continued to reduce its stake in BT Investment Management (now renamed as the Pendal Group). These moves can be seen as acknowledging that the costly exercise of creating vertically integrated financial supermarkets was a mistake. Whilst some of these moves to sell these carefully constructed divisions may be attributed to the events of the Royal Commission, some of these sales were consummated well before the titans of Australian finance faced the harsh light of the witness stand.

Profit growth

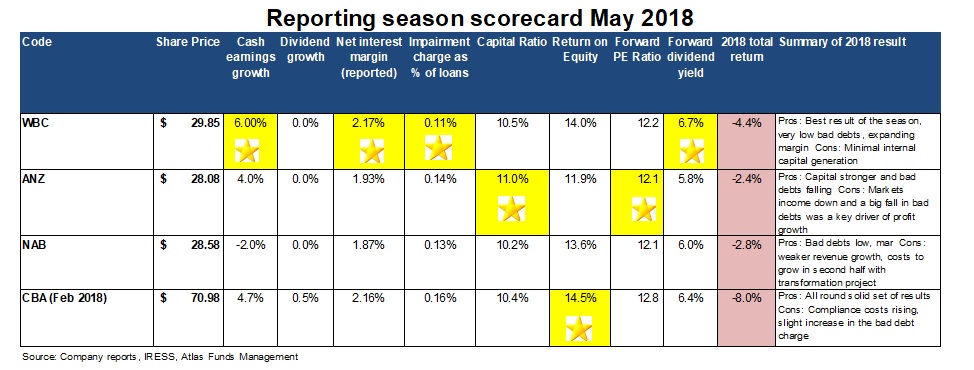

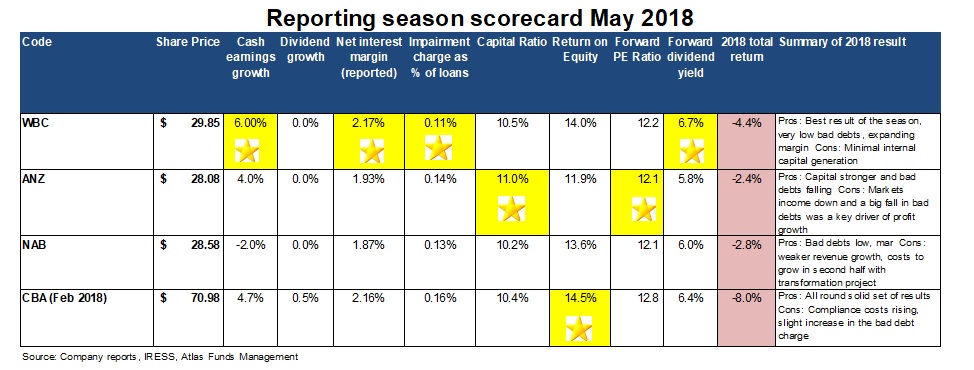

Across the sector profit growth was roughly in-line with the credit growth in the overall Australian economy. Westpac reported the strongest cash earnings growth across the banks courtesy of keeping costs under control, very low bad debts, and the sound performance of their core domestic businesses. NAB brought up the rear in May due to the combination of weaker revenue and elevated costs even when the restructuring charges are excluded.

Gold Star

Bad debts

One of the biggest drivers of earnings growth over the last few years has been the ongoing decline in bad debts. Falling bad debts boost bank profitability, as loans are priced assuming that a certain percentage of borrowers will be unable to repay and that the outstanding loan amount is greater than the collateral eventually recovered. Bad debts fell further in 2018, as some previously stressed or non-performing loans were paid off or returned to making interest payments. This resulted primarily from a buoyant East Coast property market and higher commodity prices. Further, at the big end of town there were no major corporate collapses over the past six months which kept corporate bad debts low.

Westpac gets the gold star with a very small impairment charge courtesy of their higher weight to housing loans in their loan book. Historically home loans attract the lowest level of defaults.

Gold Star

Shareholder Returns

Across the sector dividend growth has essentially stopped, with CBA providing the only increase of 1 cent over 2017. With relatively benign profit growth a bank can either increase dividends to shareholders or retain profits to build capital (thereby protecting banks against financial shocks) – but not both. In the recent set of results, the banks have held dividends steady to boost their Tier 1 capital ratios to get close to the APRA mandate of a core tier 1 ratio of 10.5%.

Looking ahead, there may be some capacity to increase dividends as the rebuild of bank capital to APRA’s standards is largely complete. ANZ shareholders can expect capital returns in the form of further on-market share buy-backs as the proceeds from the sale of their wealth management and insurance businesses are received. The major Australian banks in aggregate are currently sitting on a grossed-up yield (including franking credits) of 8.9%.

Gold Star

Interest Margins

The banks’ net interest margins [(Interest Received – Interest Paid) divided by Average Invested Assets] in aggregate increased slightly in 2018, despite the imposition of the major bank levy. This was attributed to lower funding costs and repricing of existing loans onto higher rates. In response to regulator concerns about an overheated residential property market – and in particular the growth in interest-only loans to property investors – the banks have repriced these loans higher than those repaying both principal and interest. For example, Westpac currently charges 6.3% on an interest-only loan to an investor, which contrasts to the 4.44% being charged to owner-occupiers paying both principal and interest. This has had the impact of boosting banks’ net interest margins, though these gains will tail off as borrowers switch to principal and interest loans.

One of the key things we looked at closely during this results season was the impact of the May 2017 Major Bank Levy on the various banks’ margins. It was apparent from looking at the numbers that this levy was passed on both to borrowers in the form of higher rates, and to depositors by offering lower rates on term deposits.

Gold Star – Australian banking oligopoly

Total Returns

In 2018 all the banks have delivered negative absolute returns, while also trailing the ASX 200 which has gained 2%. The uncertainty around the outcomes from the Royal Commission, rising compliance costs, and slowing credit growth has weighed on their share prices. CBA has been the worst performing bank as it has seen its CEO ushered to the door, faced fines for not complying with anti-money laundering laws, and has faced uncertainty around the potential impact of changes implemented based on recommendations from the Royal Commission.

No stars given

Our Take

How to approach investing in the Australian banks is one of the major questions facing both institutional and retail investors alike. We expect the banks to deliver around 3-5% earnings growth as they face low credit growth, increased regulatory scrutiny, and the sale of some of their insurance and wealth management divisions. However, if investors examine the wider Australian market the banks look relatively cheap, are well capitalised, and unlike other income stocks such as Telstra should have little difficulty in maintaining their high fully franked dividends. Additionally, their share prices are likely to see support over the next 12 months from share buybacks, as the proceeds from the sales of non-core assets come through. The key bank overweight positions in the Maxim Atlas Core Equity Portfolio are Westpac, ANZ and Macquarie Bank.