In late September Commonwealth Bank announced both the sale of its life insurance business and that they were looking at floating the bank’s funds management business Colonial First State GAM on the share market. Based on the strong performance of recent spin-offs investors are likely to have a close look at any initial public offering (IPO) of Colonial First State GAM. In this week’s piece we are going to look at the rationale behind spinning off assets to form a new company, and we will review the performance of recent company spin-offs from large companies such as BHP, Orica and Amcor.

What is a spin-off?

A spin-off occurs when a listed company parent separates a portion of their existing company into a second listed company and allots shares in the new company to existing shareholders based on their holdings in the parent company. In some situations, the parent company will also simultaneously issue new shares to new investors to broaden the shareholder base and allow the new spun-off company to begin life with a healthy financial position. In a spin-off, the newly created company takes a portion of the parent company’s assets, employees, intellectual property and debt. For example, in 2012 Woolworths’ spun-off 69 Australian and New Zealand shopping centres into a $1.4-billion listed property trust called SCA Property. Woolworths shareholders then received one unit in SCA Property Group for every five Woolworths shares held.

The ignored child gets a new lease on life

The most common reason cited for a company demerging or “spinning off” a division into a separately listed vehicle is that the smaller new firm will now be run by management totally focused on it. The theory goes that as a result of this increased love and focus and not having to compete with other larger divisions for management attention and capital, the demerged division begins to prosper.

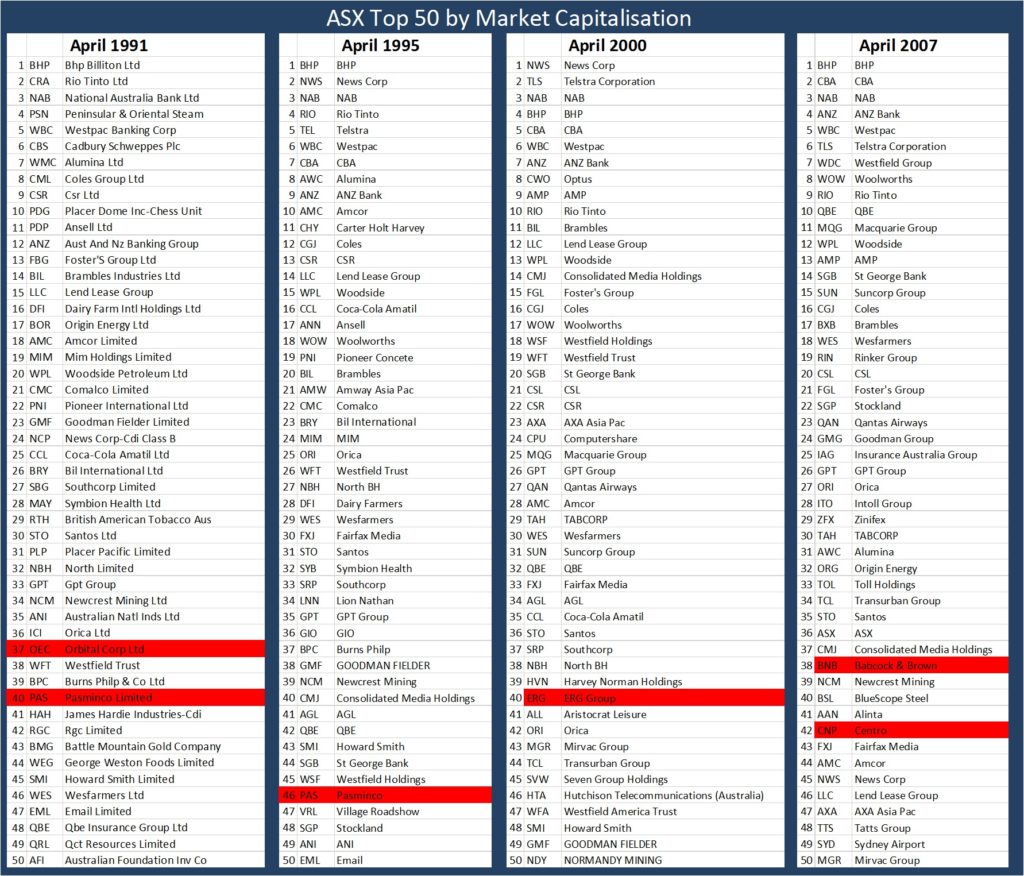

Recent examples of this can be seen in BHP’s 2015 spin-off of South32, Woolworth’s spin-off in 2012 of a portfolio of shopping centers into SCA Property Group, and Amcor’s demerger of its Australian packaging business Orora. These three spin-offs have proved to be very successful with South32 giving shareholders a total return (share price gain plus distributions) of +35% vs BHP’s gain of +16%. Similarly, SCA Property has returned +103% since it was spun out of Woolworths in 2012, against a total return to Woolworths shareholders of 8%. Since listing, Orora (which was viewed by the market as low growth compared to the dynamic world of global packaging) has returned to investors an impressive +198%: a healthy premium compared to Amcor’s still strong +68%.

From meeting with the new management teams of following their demergers, it was clear to me that they exhibited a great deal of pride in the results of their own smaller companies. Furthermore, as stand-alone companies they were able to make acquisitions to grow their businesses or buy back their stock on market. Such moves probably would not have been approved if they were still competing with Woolworths and BHP’s much larger Australian grocery and global mining business for capital.

Sum of parts worth more than the whole

In many cases the value of the two separate businesses is greater than the old combined business, even after accounting for additional costs such as a separate ASX listing and board. This is a benefit for shareholders of the parent company, as the more attractive “core” business is now re-rated upwards by the market and valued on a higher multiple. The sum of the two parts becomes greater than the original whole.

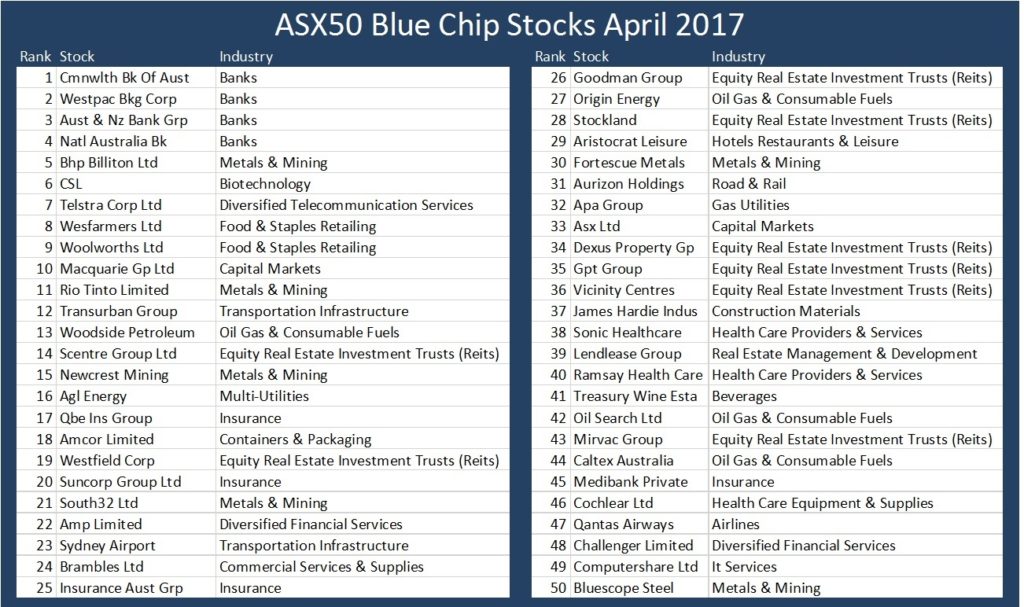

Looking at Commonwealth Bank and its fund manager Colonial First State GAM, the bank as a whole is currently being valued at 13.6 times the profits that it generated in 2017. Here the market is valuing the funds management earnings as if they were bank earnings, despite their higher margin. However, the market values stand-alone fund managers such as BT Investment Management (trading on 22 times earnings) and Janus-Henderson (trading on 15 times earnings) on higher multiples, reflecting the higher profit margins and low capital requirements for fund managers. Using a mid-point of these valuations, Colonial First State GAM would be valued at $4.5 billion, an uplift from the $3 billion that their profits from 2017 are currently being valued as part of Commonwealth Bank.

Spinning off a management headache?

Whilst the above more recent spin-offs have all outperformed their parents, it would be wrong to see that all spin-offs from large companies make great investments. In some situations, a spin-off can be prompted by management foreseeing that a division of their business is likely to face issues in the future, that may spill over and impact their core business.

Arrium

BHP has previously spun off divisions in the past that they deemed less desirable. In 2000 BHP demerged their long steel division (Arrium née OneSteel), and in 2002 their flat steel division BlueScope. This was motivated by the view (which proved to be correct) that greater returns could be made from digging ore out of the ground and directly shipping it to China, compared to manufacturing commodity steel in Australia. Furthermore, BHP was able to “spin-off” the industrial relations headaches that are a feature of the heavily unionised steel manufacturing sector.

From listing up until 2008, BHP was criticised for letting go of their steel manufacturing businesses. It might face similar opposition to spinning-off South32, however often the genius behind this course of action does not become apparent for several years. Arrium was delisted in 2016 after a well-publicised insolvency. Whilst BlueScope has performed well over the last few years it still remains 74% below the issue price courtesy of dilutive capital raisings in 2011, and in 2009 required to keep the wolves from breaking down the steelmaker’s doors.

PaperlinX

In 2000 Amcor spun off PaperlinX (now called Spicers) their stodgy printing papers division. However by 2003, Amcor was being criticised in the press after PaperlinX’s share price had risen from $3.17 at listing to $5.40. Concurrently, the PaperlinX was expanding globally after paying $1 billion to buy Europe’s largest fine paper merchant and became the world’s largest paper merchant.

The following decade was particularly unkind to PaperlinX investors as the paper business consistently shrank globally with the growth of electronic communication and document transfer technologies. Currently the company’s share price sits at 3.2 cents and one could make the case that Amcor’s management team, in spinning off a low-growth declining business, removed a division that would have consumed both shareholder capital and management attention. These negative factors ultimately would have arrested Amcor’s share price growth over the past ten years had they held on to their paper business.

Our Take

Whilst the above suggests that spin-offs can unlock hidden value for shareholders, there are downsides. Two separately listed companies result in the additional costs of maintaining two separate listings on the ASX such as two separate boards and management teams. We are likely to have a close look at any initial public offering (IPO) of Colonial First State GAM, especially on price weakness if a number of shareholders sell their entitlements just after listing. Unlike steel making or printing paper, funds management in Australia is a robust business and Colonial is a significant player with a powerful brand.